Why tackling has become high stakes

At the 2011 Rugby World Cup, Ireland defence coach Les Kiss first unveiled a new shock weapon in the pool game against Australia.

Instead of defenders targeting the ball-carrier’s legs for the ‘chop’ or ‘cut’ tackle, Kiss taught his players to attack the upper body, lock on to the ball and aim to hold the ball-carrier up off the ground.

Why? The answer lay in a wrinkle of law. Law 16.17 states that:

A maul ends unsuccessfully when:

a. The ball becomes unplayable.

b. The maul collapses (not as a result of foul play).

c. The maul does not move towards a goal line for longer than five seconds and the ball does not emerge.

d. The ball-carrier goes to ground and the ball is not immediately available.

e. The ball is available to be played, the referee has called “use it” and it has not been played within five seconds of the call.

In all of these cases, the ball is turned over to the defending side via the award of a scrum feed.

In the game itself the tactic worked a treat, with the following successful turnovers highlighted in short video by the Australian analyst Scott Allen:

Since its introduction back in 2011, the choke or hold-up tackle has evolved considerably. In all but one of the examples from the Ireland-Australia game, at least four, and as many as six defenders were absorbed in the maul.

As countering methods developed over time, attacking teams began to exploit that high commitment of numbers and slice open the depleted defensive lines, and wider line spacings it left behind on next phase.

The hold-up tackle is still very much on the cutting edge of defence, but it has had to transform itself in order to remain there. One the most significant points in its favour currently is that it implies a deceleration, rather than acceleration into the collision between attacker and defender.

As Les Kiss himself commented,

“By virtue of the tackle itself you have to cool your jets a bit and wrap a bit more to get under the ball, so you actually have less heat in the collision to actually affect it properly.”

“When you do a lot of chop tackles there’s a danger there where you can get hit by knees and hips as well, so the baseline for us, we just try to coach as good technique as we can in whatever tackle we use.”

This is an important safety issue in a professional climate which is becoming so sensitive to the long-term damage of repeated head traumas.

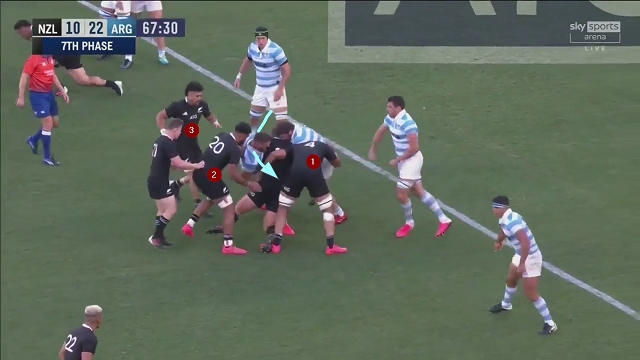

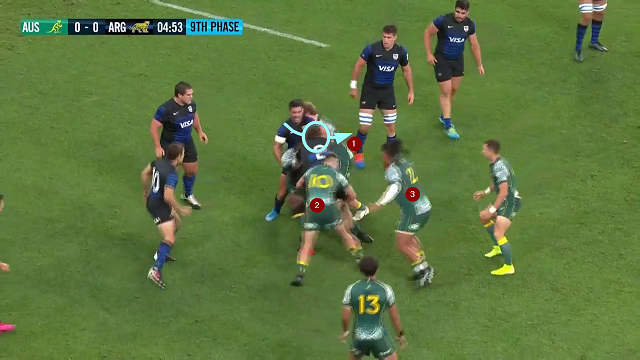

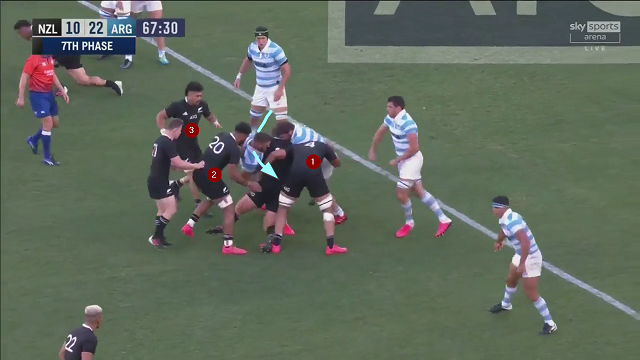

At the recent Tri-Nations tournament, the excellent Argentine defence gave several illustrations of the modern version of the hold-up tackle, against both the All Blacks and the Wallabies:

The three instances offer a variety of ball-carriers – from a prop (Joe Moody) to a number 8 (Hoskins Sotutu) and a powerful wingman (Marika Koroibete).

The following features are key:

• One or two-man commitment. The defensive commitment in terms of numbers has reduced from 4-6 in the Australia-Ireland video, to one or two defenders at most:

In all three instances, the number of attacking players committed via the carry or the cleanout exceeds the number of defenders committed to the tackle by +1. That means an advantage in numbers for the defence on the next play.

• Five second ball (no turnover scrum). The aim of the choke tackle is no longer to generate a scrum turnover. It is simply to hold the ball carrier up for five seconds plus, allowing the defence to regroup comfortably for the following phase. From the first contact to the ball being presented to the half-back, there is a delay of respectively, seven, six and five seconds over the three examples. That is equivalent to very slow ruck ball.

• Legal ‘Offsides’ defender. With no ruck having formed, there is no offsides line for the defender, who is free to swing around behind the ball-carrier in all three sequences and legally block release of the ball, or even to attempt a strip (in the Australian example):

A defender at the ruck does not have the same latitude under the laws.

• Deceleration of the cleanout. The hold-up tackle effectively neuters the cleanout, which can no longer create momentum by driving dynamically over the ball in a body position parallel to the ground. The body positions of all the support players are very high and static:

In the foreseeable future, we can look forward to seeing a lot more of these techniques in action. They are safer high tackles because the defender is absorbing energy in the collision rather than trying to initiate it, and targeting the ball rather than the head or neck. There is likewise, no danger to the knee joint as there is in a chop tackle.

At the same time, the technique can be operated with only one or two defenders in order to create slow ball for the next attacking phase, and grant the defence an advantage in numbers and/or organisation. The ‘choke’ has become high stakes indeed.