Aggressive ball-placement options at the Women’s World Cup final

The women’s game is on the rise, especially after the outstanding World Cup final played last weekend between the New Zealand Black Ferns and the England Roses. At the Kingspan stadium in Belfast, New Zealand eventually came out on top by 41 points to 32 in a thrilling 11 try game.

The women’s game also has the virtue of being different in character to the male version of rugby. An IRB analysis of the women’s game back in 2006 pointed out how the ball-in-play time was constantly rising – it went up 20% between 2002 and 2006 for example – bringing the number of rucks set and passes made close to those being achieved in the men’s game.

The biggest single difference between the two versions of rugby is in the area of kicking. In the 2006 IRB report, it is noted that penalties kicks at goal were far less frequent in the women’s game, in a ratio of roughly 1:3 compared to the men’s version. The 11 tries scored by both sides in the Belfast final far outweighed the meagre two penalties by England’s Emily Scarratt.

Kicking out of hand is also both less frequent and less effective than it is in the men’s game. In a study comparing the Women’s World Cup in 2014 with the men’s event one year later, one of the conclusions is as follows:

Findings suggest that in the men’s game, winning teams kicked a greater percentage of possession in the opposition 22–50 m [area] with a view to gaining territory and pressuring the opposition (winners = 16%, losers = 7%). In the women’s game successful teams adopted a more possession-driven attacking approach in this area of the pitch. Successful women’s teams appear more willing to attack with ball in hand following a kick receipt and adopt a more expansive game through attacking with wider carries in the outside channels.

With shorter clearances both infield and to touch, teams who are able to efficiently recycle possession in the women’s game can camp in the opposition half for longer periods of time.

As you would expect in a possession-based game, technique in contact becomes a major feature of the play. In his excellent new starter series on The Rugby Site, Ben Herring explains the foundation factors in good ball-placement after a tackle has been made. He explains how an active decision and an active movement must be made after the ball-carrier hits the deck – it is not enough to push the ball back passively, a definite movement must be made to ‘curl’ the body in the direction of the placement, moving the ball further away from the opposition.

The movement on the mental level must be just as decisive – an active rather than a passive process. There are three basic possibilities when the ball goes to ground:

1. Offload off the ground if support is available and the ball is free

2. Allow the ruck to form and place the ball backwards

3. Release and regather by the ball-carrier themselves

Of the three options, it is the third which is the most under-used and under-coached, particularly in the northern hemisphere. The ball-carrier is able to release the ball, get to his/her feet and play it again by law, and this can be a valuable technique to buy time for support to arrive, or attack via a kind of enhanced pick and go.

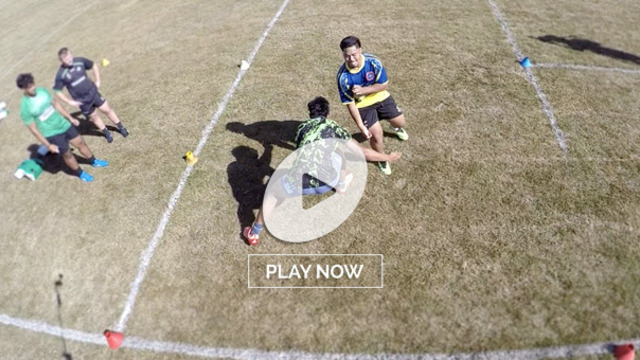

The Black Ferns scored a try which turned momentum decisively at a crucial moment in the final by using this technique:

Here is the same sequence from behind the posts:

New Zealand employed the pick and go right through the middle of the Roses’ defence in the ‘red zone’ (the last 25 metres of the field) throughout the game. Here the Black Ferns’ loose-head prop Toka Natua drives up the middle before being tackled by England scrum-half Natasha Hunt.

In the sequence from behind the posts, it is clear that the tackle has ended, and that Natua has released the ball and then gets to her feet in order to play it again as required by laws 15.5 (b) and ©:

(b) A tackled player must immediately pass the ball or release it. That player must also get up or move away from it at once.

© A tackled player may release the ball by putting it on the ground in any direction, provided this is done immediately.

If the England #9 had maintained her grasp on Natua, she would have forced her to ‘curl’ and play the ball backwards as Ben Herring describes. Once out of the grasp of the tackler, Natua is however free to release the ball directly in front of her body, get to her feet and play it again.

The #9 is also the defender usually assigned to the ‘boot’ space – the area just behind the site of the ruck. She organizes the defenders in that zone and picks up any runners who have broken the inside defence. Once she has been absorbed in the previous tackle in this instance, her role is not upheld by any of the other England defenders. The England #18 rolls around to the guard position on the far side, while #17 (in the blue hat) stays at near-side guard, which means that the area straight up the middle is not policed at all:

Summary Lessons for the game as a whole work both ways – from the men’s game to the women’s and back again.

One of the lessons to be learned from the women’s World Cup final was the value of accurate techniques in close contact. The effort at presentation of the ball must be an active one. There are choices to be made (offload, curl or release-and-regather) on the mental level and a there is a physical effort to be made from the strength of the ‘core’.

As the England Roses’ coach Simon Middleton said afterwards, the choices of the New Zealand women in that area made all the difference to the winning and losing of the match:

“They played a really smart game. When (they) did get the ball they had a massive physical presence, they are so good at playing that short game, that was the story of the second half… We did react, but we literally couldn’t stop them. They were very efficient at keeping the ball. Full credit to them…”