Coaches and players are always on the lookout for ways to get an edge in the grey areas of the game, and there is no area more pliable to interpretation than the breakdown. There are no less than 38 possible offences in total, which can be committed by attack and defence in this critical aspect of the game.

The defensive side will try to push the legal envelope as far as possible, leaving it until the last moment for the tackler to roll away from contact, or even having him/her rolling back towards the ball rather than away from it! As in my previous article on the double jackal https://www.therugbysite.com/blog/breakdown/how-to-double-up-at-the-defensive-breakdown, if you can keep the tackler involved as a shield for the pilfer, you are in business defensively.

It is all a far cry from the noble intentions behind the breakdown overhaul inaugurated in June 2020. An excellent summary of the changes, explained by New Zealand Rugby Referee Manager Bryce Lawrence and international panel referee Paul Williams, is available here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PPS9Z5hzPPw.

In that wrap, the tackler’s responsibilities were clearly set out in black and white:

“Tacklers must roll east to west and not impede [the] attacker’s ability to clean out. If they fall between the ball and the attack, they take all responsibility to get out. If they can’t, they will be PK’d.

To reward the Jackal [pilfer], the tackler must not impede the cleanout. Dealing with the tackler is the number one [officiating] priority.”

The fog of war seldom allows a black and white assessment by the referee, of course. More typically, he or she will find themselves in the gloam of the grey area, attempting to weigh up the obstructive impact of the tackler by split seconds, or the breadth of a hair.

The attacking side can help the referee and the game as a spectacle, by setting ‘tackle traps’ which ensure the official becomes aware of potential infractions of their number one priority – by pushing the grey action back into the black and white, so to speak.

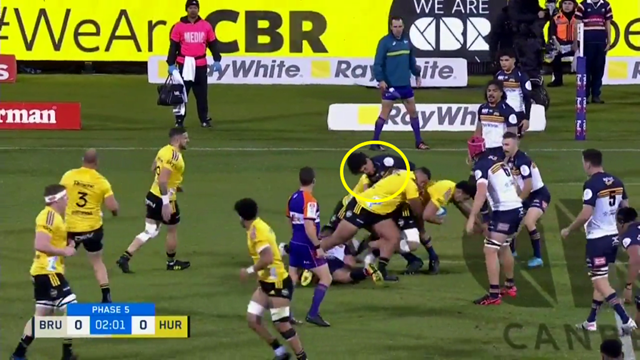

Let’s look at some recent examples of how the tackle trap works in practice, with reference to the Super Rugby Pacific quarter-final between the Brumbies and the Hurricanes. Coincidentally, it was refereed by Paul Williams, who appears in the illustrative video.

The high tackle technique, designed to choke off an early release by the ball-carrier, keep bodies high and potentially generate a maul turnover, also leaves the tackler vulnerable to a trap if the ball can be forced to ground:

High tackle technique invariably means one tackler moving abreast, and sometimes forward of the ball-carrier. When the ball goes to deck, the tackler can easily find themselves sandwiched by the cleanout with nowhere to go – let alone any opportunity to roll ‘east to west’.

In this instance, Brumbies second row Darcy Swain gets trapped behind the two Hurricanes cleanout players, and halfback T.J. Perenara does the rest, pointing out the obstruction created to Paul Williams and drawing the penalty. The attack is under no obligation to let the tackler get out of the cage he has built for himself.

The Brumbies got their own back just after half-time:

In this instance Ardie Savea swings around behind the ball-carrier (prop James Slipper) in order to create a typical choke isolation, but when ball goes to ground, he is trapped underneath Folau Fainga’a and obstructing the presentation of the ball.

Low tacklers can also be targeted for the trap when they delay their east-west roll away from contact, or roll back in towards the ball:

In this case, the low tackler (Fainga’a) is rolling the wrong way – into towards the ball – and is rightly trapped by Canes number 7 Du Plessis Kirifi for his trouble. Kirifi has pinned the Brumbies hooker and has no intention of letting him off with a slow roll which has effectively delayed the speed of ruck delivery.

The attacking number 9 often has a crucial role in trapping the low tackler:

The Hurricanes number 4 is making a legitimate attempt to get out, but he is still creating a platform for the counter-ruck, so Nic White traps him with his knees as he bends down to pick up the ball.

The other advantage of running the trap is the moment of relaxation created in the defence, believing that the penalty will lead to a new sequence of play:

Another high tackle, and another penalty from the ensuing offensive trap leaves the Brumbies defence hopelessly narrow and condensed when the Hurricanes play through the penalty, with a cross-kick out to the right touch-line:

Summary

The tackle trap is not really a cynical play at all, it is an important antidote by the attacking side to cynical play at the tackle by the defence. It moves illegalities occurring within the grey area back out into the refereeing black and white, and as such it is a valuable way of maintaining a positive tone in the game as a whole. Ultimately, it allows officials to implement the new breakdown rules as they were originally designed back in June 2020, and that has to be a good thing.