One of the most popular commentators and ex-coaches in American Football was the great John Madden. He was a Superbowl winner as a coach with the Oakland Raiders in the 1970’s but he was arguably even more successful as a commentator and TV personality subsequently. His brand of jovial humour, his love of the unloved and bear-like 300 pounders on the offensive line, and his unapologetic passion for the game infected every viewer. You watched an NFL game as much to hear John Madden talk as you did to watch the players play.

One of Madden’s most famous pronouncements occurred in a game between the Cincinnati Bengals and the New York Jets in 1983. When a receiver is going out of bounds having made a catch, he is required to get both feet down on the ground for the receipt to be legitimate. On this occasion, the receiver got his knee down first and the catch was called good: ‘Well. I guess one knee equals two feet’ chuckled Madden on the telly. He wrote a best-selling book with the same title only three years later.

The phrase now makes perfect sense in the world of the high tackle in professional rugby. High tackles are very popular because they prevent offloads and under the current law, they can often lead to turnover scrums when the referee calls a maul.

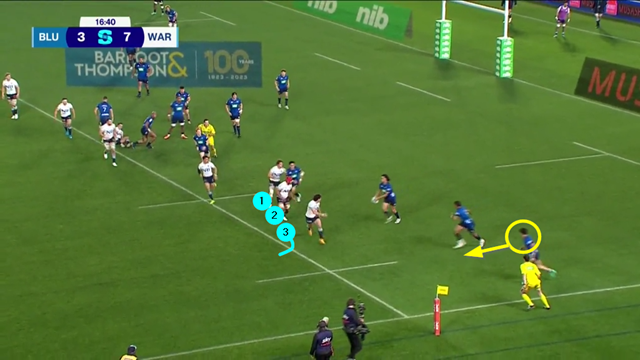

There were at least three successful examples executed by the Blues in the recent Super Rugby Pacific quarter-final between the men from Auckland and the Waratahs. Her are two of them:

There are two moments of ‘clear and present danger’ amply underlined in the clips. As soon as a defender can hook his arms underneath the armpits of the ball-carrier, the attacker effectively loses control of the upper half of his body. When a second defender moves around the back to isolate him from his support, it is ‘curtains’ for the ball-carrier.

When he eventually gets to ground (Mark Nawaqanitawase in the first example) the defence is already primed for the counter-ruck; if he stays up (Michael Hooper in the second instance) it will inevitably draw a turnover scrum call from the ref.

The solution is to drop body-height quickly and dramatically, and get at least one knee to the ground immediately as soon as the ball-carrier feels the ‘hooks’ digging in. Even one knee on the deck is enough for the official to call for instant release in the tackle – so one knee down is as good as two feet off the ground:

Here Blues’ wing Mark Telea drops both knees as soon as he feels the high tackle technique beginning to threaten a turnover. The referee calls for release as the tackle is now complete. When the Waratahs try to prolong the contest and rob Telea of the ball, they are breaking the law and a penalty is rightly awarded.

Mark Telea is a rewarding object of study in this respect. He is so strong in tight contact situations that it is tempting for him to stay alive on the carry for as long as possible:

Telea sheds no less than four tackles on a short, winding run into midfield, but he judges the moment for a swift drop to the deck exactly right. He does not become infatuated with his own success on the run. It leaves New South Wales short of numbers on the following phase, and the Blues run away to score an unlikely long-range try from a position deep in their own end.

Summary

That is an inviting prospect when the attack can shift the ball away from established high tackles, which frequently consume as many as three or four defenders in order to be effective. If the ball-carrier can judge the moment to drop his body height right and get a knee to ground decisively, it can leave the D short for the following phase. One knee equals two feet, as John Madden used to say – but it can also mean a line-break, or even a try.