How Japan are finding an edge at the World Cup

There is a Japanese proverb which says, Koketsu ni irazunba koji-o ezu. The literal English translation is “If you do not enter the tiger’s cave, you will not catch its cub”. A less literal version might be, ‘nothing ventured, nothing gained’.

Japan have proven very fortunate hosts of the 2019 Rugby World Cup, and much of the success has been the result of positive planning invested in it, both on and off the field.

Off it, Japanese supporters have been encouraged to adopt a second team as their own; on it, the Kiwi coaching combination of Jamie Joseph and Tony Brown have instilled New Zealand playing values within a Japanese playing culture. In both cases, there has been a very profitable cross-fertilization of ‘foreign’ ideas.

In a squad where the biggest player (Christchurch-born second row Luke Thompson) is only 1.96m tall and weighs just 108 kilos, Joseph and Brown have turned to mobility in the forwards and ball-handling in the backs, to make Japan’s compelling case for inclusion in the knockout stages of the competition.

Japan use the full width of the field on attack more consistently than any other side in the tournament, but it is not a matter of swinging the ball aimlessly from one side of the field to the other; rather, of accurate inter-passing between backs and forwards in midfield designed to exploit overloads in the wide channels.

Most of the top defensive teams in the world are set up to defend between the two 15 metre lines, and they will rely on defenders ‘folding’ in behind the last man to cover the space beyond it.

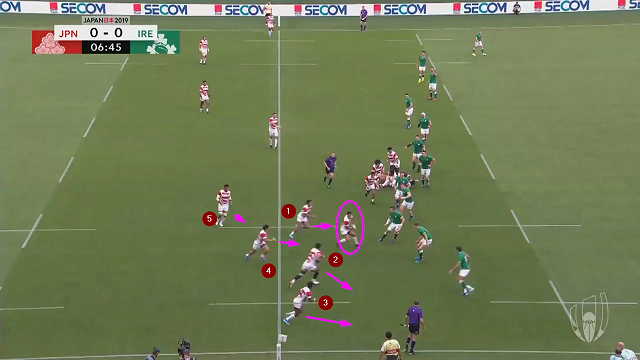

Japan sets up its attacking alignment to put the finger on this space. Here are a couple of simple screenshots from their historic pool win over Ireland:

Firstly, it is essential to point out that Japan are not a ‘one-pass’ attacking team. Far from it. They rarely play off 9, they play mostly off 10 or 12 – the first and second receivers, often with a pod of forwards used to connect the key distributors with another pass.

It is the ability to make the second or third pass accurately which allows support to flood into the 15-5 metre channels beyond them. In the first example, the ball goes through the hands of the number 10 Yu Tamura (circled) in order to reach no fewer than five attackers ready to enter the wide right 15-5m zone beyond him. As the screenshot shows, the Ireland defence is reluctant to match numbers on the extreme edge of the field – it is defending five attackers with three players in green.

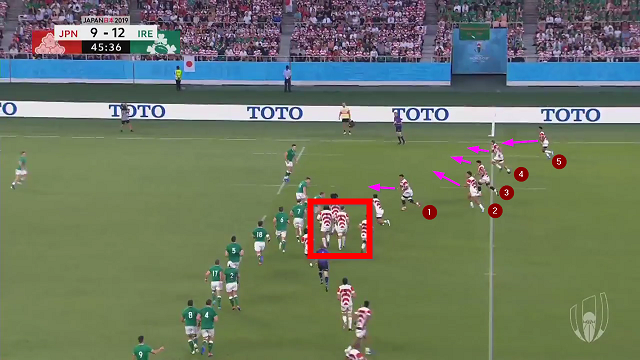

In the second instance, the ball has already travelled through the hands of Tamura and the three-man forward pod outside him (in the red rectangle) before it reaches the second receiver. Outside him, there are five Brave Blossoms’ attackers overmatching two Ireland defenders in the right 15-5m zone.

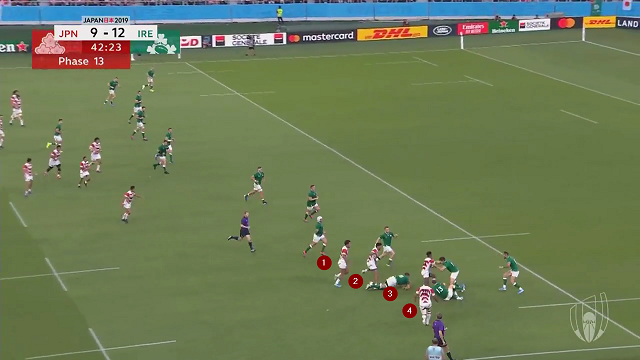

Now let’s look at this structure working out in real time, during a long sequence at the tail end of the first period:

Japan achieve width to the right initially by inserting their number 10 in between the halfback and the first pod of forwards. That moves the point of attack outside the bigger Irish forwards, and into to a space between the last Ireland forward (number 7 Josh van der Flier) and the first back (number 10 Jack Carty). This is a vulnerable spot from which Ireland are unlikely to be able to deliver a dominant frontal tackle, or slow down the ruck ball.

A quick, two second presentation then allows Japan to explore the edge on the next phase. The Irish defenders are having to move across the field instead of straight up, so already their attitude has become more passive. Once again, Japan have managed to pack four attackers into the key target area between the 15m and 5m lines:

Less than 20 seconds later, the Brave Blossoms were testing the opposite edge of the field:

The ball goes out through the hands of the forward pod to lead the defence upfield, then it is overcalled to the Japanese 10 and 12 behind them. The right edge of the Ireland defence, manned by number 14 Keith Earls, is clearly stressed by the presence of three Japanese attackers in his area.

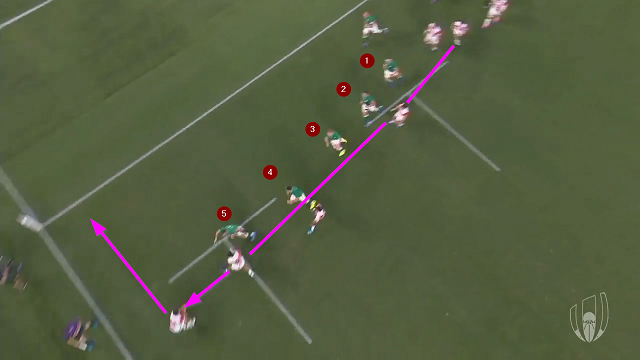

Perhaps most impressive of all is Japan’s willingness to both maintain their width, and use it immediately upon an opportunity arising near the opposition goal-line. Most teams will play it safe and rely on the number 9 and the ‘piggies’ to get themselves across the whitewash in these circumstances.

When the ball reached first number 12 Ryoto Nakamura at first receiver, there is no thought of ‘tucking’ the ball in and charging ahead into a green wall. He throws a beautiful long cut-out pass out towards his centre partner Timothy Lafaele instead.

Lafaele converts the opportunity with an all-in-one transfer to wing Lomano Lemeki outside him. The most interesting aspect about the final play is the spacing of the defenders in relation to their opposite numbers:

Ireland are matched up evenly, five-on-five, but it is the spacing of the Japanese attack allows it to achieve success. In the critical target area near the 5m line, Japan has stacked up in a three-on-two versus Earls and the man inside him (Conor Murray). The accuracy of the first two passes ensures that the extreme spacing counts, and Ireland pay the ultimate penalty.

It is a beautiful example of how accuracy on the pass and intelligent spacing out wide can still unlock the quickest of rush defences – after all, a defence which wants to step forward cannot step sideways at the same time. You just need the courage of your convictions to enter the tiger’s cave, and steal its cub!

.jpg)