One of my earlier memories as an analyst was the preparation for Wales’ climactic Six Nations game against Ireland in 2005. Wales had already won their first four matches that season, so a victory in the final game would pave the way to a Grand Slam – the nation’s first in 27 years.

Ireland’s attack at that time was very well-balanced. If anything, it was slightly better going left-to-right than it was moving in the other direction, and that is a rare characteristic in the professional era. Most sides tend to be better at shifting the ball from right-to-left, simply because the majority of players are right-hand dominant.

The Irish outside-half Ronan O’Gara was an outstanding passer off his left hand and well capable of putting legendary centre Brian O’Driscoll into space with a stream of long and accurate deliveries. That caused the defensive teams they faced a lot of headaches, because the prospect of ‘BOD’ playing in space with his back three was a forbidding one!

That game went a long way towards convincing me of the value of distributors who can offer superior quality with their left-to-right passing. As recently as November 2021, one of the salient features of Ireland’s performance versus the All Blacks was the slickness of attack off ‘the wrong hand’. Ireland included a naturally left-sided player (Leinster left wing James Lowe) as an extra midfield distributor on left-to-right movements:

In both cases, Lowe is ‘ghosting’ the play off the blind-side wing, and the speed-of-attack visibly changes gear when he shoots the ball across to Jack Conan in the first example, and hits fellow wing Andrew Conway with a longer delivery in the second.

This is the kind of contribution that Lowe regularly makes at provincial level for the current Pro 14 champions. The following sequence comes from a second half lineout in Leinster’s win over Montpellier in the Heineken Champion’s Cup:

The key delivery is the third pass from Lowe. The blind-side wing enters the line outside Johnny Sexton and throws a superb long pass out to Jimmy O’Brien off his dominant left hand, and the outcome is an effortless 20 metre gain down the right side-line for the Irish province.

Another back who exercises a transformative effect on the back-lines in which he plays is Henry Slade, the Exeter and England midfielder. Slade’s background at number 10 in the England age group sides encourages both teams to insert him even earlier in left-to-right back-line movements than Lowe – typically at first receiver off the set-piece:

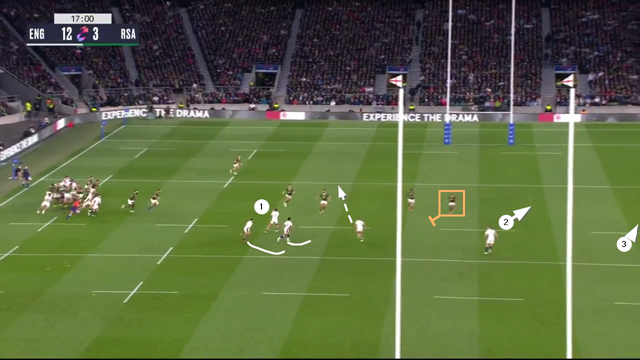

From a scrum out on the left side-line, England move Slade into first receiver with the nominal number 10 (Marcus Smith) ghosting in behind along with blind-side wing Jonny May. England knows that the South African open-side wing (number 11 Makazole Mapimpi, in the yellow square) will defend hard and narrow, but the play only works because of Slade’s outstanding ability to pass the ball accurately off his left hand. He can deliver the ball 20 metres into the top corner of the receiving ‘strike zone’ for the target Freddie Steward, leading him upwards and outwards in the direction of the space England want to exploit.

Just two passes take the men in white all the way up to the South African five-metre line, and Steward converted the position into a try a couple of phases later.

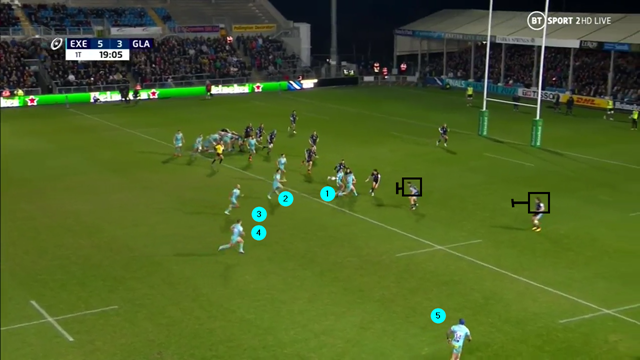

That kind of long-passing ability off the left hand forces compromises from the defence. In the recent Champion’s Cup game between Exeter and Glasgow Warriors, Slade again appeared at first receiver on a left-to-right movement from set-piece:

His presence at first receiver engages the attention of all of the Glasgow defenders outside him, so that they have no chance of adjusting to the tidal wave of Exeter attackers swinging around to the open side of the field off the England man’s last-minute, pull-back pass:

Summary

That is what a good left-sided (or ambidextrous) back can do for you, opening up the full width of the field to both sides and placing intolerable pressure on the defence. The ‘lefty, righty’ combinations so popular in Cricket and Baseball, in both batting and bowling scenarios are just as valid in the game of Rugby.

.jpg)