The raw stats from New Zealand’s final against South Africa at the Stade de France make for fascinating reading. Despite losing their skipper Sam Cane to a red card in the 28th minute, the figures were all heavily loaded in the Kiwis favour. Even with one man less, the All Blacks dominated possession of the ball.

They enjoyed 24 minutes of active possession time to the Springboks’ 16, set 120 rucks to South Africa’s 56 and forced the men in green to make more than twice the number of tackles (209 versus 92). They carried the ball 64 more times than the Boks and won the line-break battle 7-4. With 60% of possession and 53% of territory, it was looking good for New Zealand.

Scratch beneath the surface, and a different set of truths emerge. New Zealand only had 37% LQB (lightning-quick, or sub three-second ruck ball) when they would typically be expecting a ratio closer to 60%. While 31% of the ball the All Blacks received reached the target area between 10-20 metres out from the ruck, only 6% reached the edge (+20 metres from ruck-side).

With that in view, let’s examine some of the scenarios where New Zealand found it difficult to achieve their traditional width on attack, and where the South African rush defence, playing the ball rather than the man. made its own indelible mark on proceedings. Most of the examples focus on situations where the numbers on either side were equal.

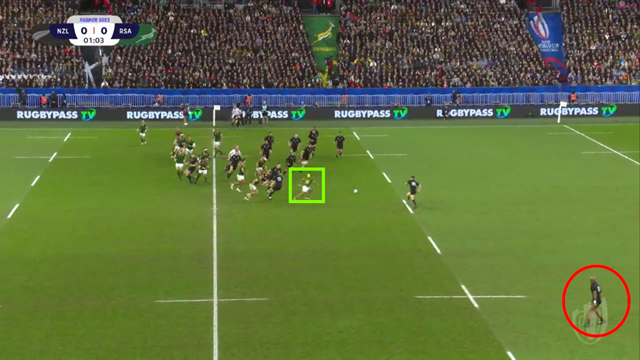

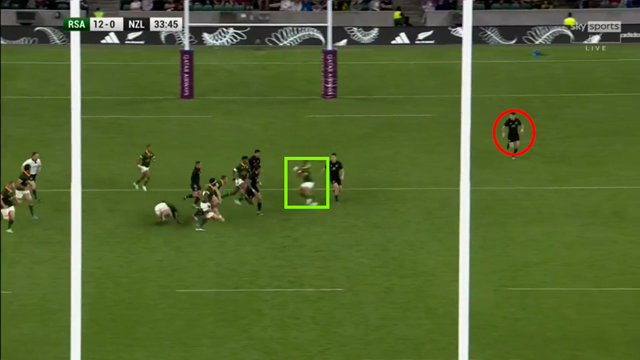

The Springboks made their intentions clear right from the start of the game:

Look where the Springbok right wing Kurt-Lee Arendse is defending, compared to the Ireland wings in the clips from the Ireland-New Zealand game in the partner article:

Arendse is attacking the second pass, and his opposite number (New Zealand #11 Mark Telea) is fully half a pitch away on the left-hand side-line. That is what ‘playing the ball’ really means on defence. Arendse had already given notice of his intention in the warm-up game between the same two nations at Twickenham:

https://youtu.be/bjKVlCyUznQ?si=KtQFeFsRGoWbl9Lc&t=124

The diminutive Springbok right wing cuts loose two attackers outside him and breaks on to the ball after a half-break by Kiwi second five-eighth Jordie Barrett.

The use of the second pass tended to leave the All Blacks further behind the advantage-line than where they began:

On both phases, Beauden Barrett is inserted in between two forward pods, but by the time the second pass has reached its target the defence has closed and prevents the ball moving further towards the far edge of the field. The outcome is a loss of ten metres and an exit kick to relieve pressure.

In both these instances, the ball cannot move past second receiver before the play is shut down and a turnover (the first by fumble, the second by pilfer at the breakdown) is forced. The onside wing (#11 Cheslin Kolbe in the first sequence, and acting right wing ‘Faf’ De Klerk in the second) is playing high upfield, not ‘off’ as in the 2013 samples, and he is in position to stop any further attacking activity in that sensitive zone between the 15m and the 5m lines.

On the one occasion when the All Blacks did manage to unlock the rush, it was due more to a missed tackle on defence rather more than to creativity on attack:

<blockquote class=”imgur-embed-pub” lang=”en” data-id=”a/JcSH87x” data-context=”false” ><script async src=”//s.imgur.com/min/embed.js” charset=”utf-8”>

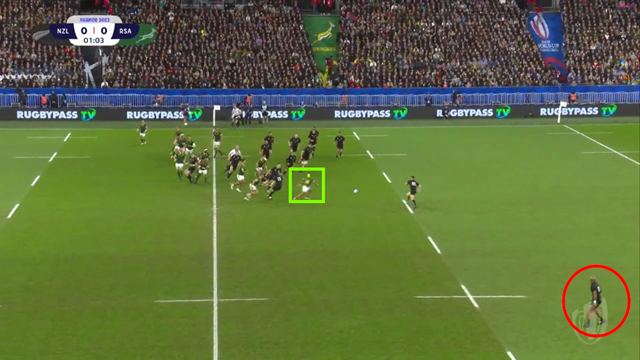

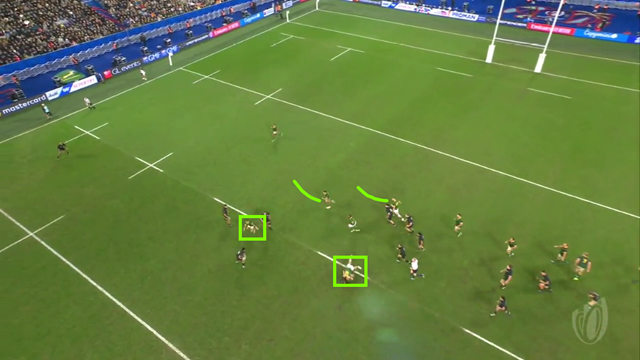

Arendse has Richie Mo’unga firmly in his gunsights after the pass from Jordie Barrett, but the Crusaders’ #10 skips through the tackle to set up a chance for Aaron Smith on the wide left:

The overhead shot elegantly reveals how an elite rush defence works. The first line knifes from out-to-in and focuses on the passer – #13 Jesse Kriel on Barrett and #14 Arendse on Mo’unga – while the ‘drift’ (from #12 Damian De Allende) is only triggered after the initial breach has been manufactured, in the second line of defence. In the event, the try was ruled out for an earlier knock-on at the set-piece.

Summary

Over the last cycle and for a couple of years before that, New Zealand has had problems in coming to grips with the nature of rush defence as practised in the northern hemisphere, and by the Springboks. Has the puzzle been truly solved? In their two big games against teams based on rush defence (France and South Africa) at the 2023 World Cup, the All Blacks only generated three tries, and ultimately they lost both matches. <b<There is still some work for the incoming head coach Scott ‘Razor’ Robertson to do.