Ahead of the last World Cup in 2019, World Rugby produced a series of useful guides, offering very clear and concise summaries of various aspects of the game. One of them was entitled “Drift or Blitz: what is really the best form of Defence?”

It is still very much a valid query at all levels of the game. One of the questions I am asked most frequently is ‘why is Drift less popular as the staple form of defence?’ Increasingly, the trend has been less to run laterally, push off from the inside out and drive attackers towards the safety of the side-line, and far more to make tackles on square in the front line, closing down the space before the ball ever reaches the edge.

The most extreme form of Drift defence is the so-called ‘Jockey’ variant, where defenders will slide backwards rather than sideways, trading metres for time as they look to reconnect in a coherent single line. Typically, this is used after a change of possession, when all the emergency lights are flashing for the team turning over the ball.

As the World Rugby article indicates,

“If the attacking team has seven players on the far side of the breakdown and the defensive team only has four, we would call that a three-man overlap.

Any overlap is hard to defend unless you employ the drift defence. As the name suggests, each defender drifts on to the attacker to their outside once a pass is made. As the defenders drift, so they reduce the overlap.”

Some recent examples from Super Rugby Pacific 2023 will help explain just why the more passive forms of defence, like the Drift or Jockey, are becoming less popular and more marginal in coaching attitudes to the game.

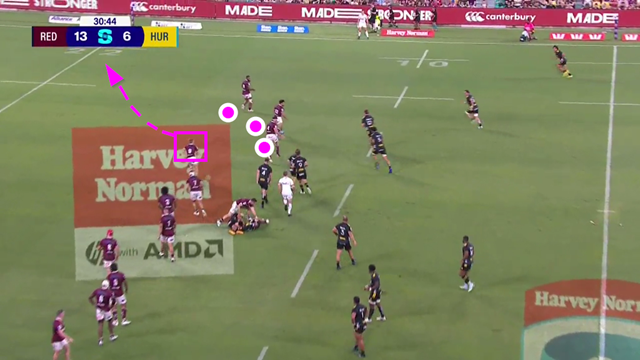

The first instance comes from a turnover return from the match between the Queensland Reds and the Hurricanes. The Reds have just blocked down a Kiwi kick and moved upfield, only to find themselves short on the left-hand side on the return:

It is a 4-on-3 overlap for the Hurricanes, and that means the Reds’ line has to adopt the unmistakeable ‘bend’ that characterizes a jockeying defence. It is looking to identify a spot further downfield where it can make the tackle, with either a defender in cover (scrum-half Tate McDermott in the rectangle) or a second coming out of the backfield linking up with the line. That spot is just inside the 22m line near the left touch.

The problem is the space traded, which more athletic and powerful modern players can use to build up an unstoppable head of steam on a thinly-defended extremity. As soon as the last defender (Reds’ wing Filipo Daugunu) engages, the odds shift in favour of the edge attacker, Canes’ centre Billy Proctor. Proctor comfortably beats both of the Queensland halves (McDermott in cover and blond number 10 Tom Lynagh from the backfield) on a canter to the try-line.

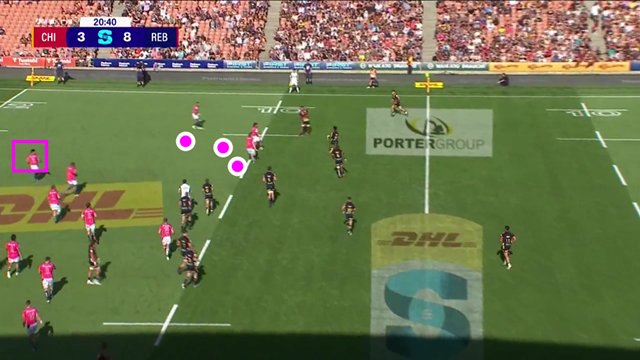

Now let’s look at a very similar example from the game between the Melbourne Rebels and the Chiefs in Hamilton:

This instance derives from kick return starting inside the Chief’s own 40m line. Once again, it’s a 4-on-3 with the defensive wing sitting off and offering a ‘tell’ to the distinct bend of a jockey drift. Once you show the attacker that you are intending to make a tackle from the side not the front, all the trumps are with the offence, and Chiefs’ wing Emoni Narawa simply skirts around the arm-tackle of Stacey Ili on the outside.

The offload then beats the two Rebels halves, one in cover (scrum-half Ryan Louwrens), and the another (10 Carter Gordon) coming out of the backfield.

One of the big issues in Jockey defence is the aerobic demands for the cover defenders. Instead of defending in line or sweeping close behind it, the scrum-half has to cover more ground in a sprint for the corner flag:

This example comes from a turnover (via a loose pass) late on in the Reds-Canes game. Once the penultimate attacker engages both of the last line defenders, there is no covering scrum-half in sight to oppose three Hurricanes on the ball out left. There is only Lynagh coming out of the backfield, and that is not nearly enough to prevent a try.

The game between the Chiefs and the Rebels also illustrated the pitfalls of trying to play more aggressively out of the Jockey shape from a lineout turnover:

In this case a defender (Rebels number 14 Lachie Anderson) comes out of the backfield more aggressively to close down the passing lane on the edge, but it opens up space for the kick down the 5m channel, with only left wing Monte Ioane left in cover to protect the entire width of the backfield.

Summary

Increasingly in the modern game, Drift or Jockey defence is slipping out on the tide of rugby fashion. Defence has to be inch-perfect, especially from changes of possession. The line defenders have to get their angles on arm-tackles exactly right in order to make a solid impact, and the last edge defender has to avoid becoming entangled with the penultimate attacker. The components of the cover/backfield defence have to be in place, and they have to be consistently effective. If any of these cues are absent, the (counter) attack will hold a winning hand.