Can the new trial kicking laws add value to the game?

On February 10th 2021, World Rugby reaffirmed its drive to keep the game moving forward, even amid the restrictions of the post-Covid era.

The three bullet points of its push to produce a more attractive product for broadcasters were as follows:

• World Rugby and Unions united in continued drive to advance game safety and spectacle

• Australia and New Zealand competitions provide high-level trial opportunity

• Variations aimed at increasing space and decreasing defensive line speed could have positive player welfare outcomes

Although most of the trial laws had first received exposure in Super Rugby Australia 2020, one year later they were extended across the Tasman, to New Zealand’s parallel Super Rugby Aotearoa competition.

The pith of the new trial laws is to reduce the impact of defensive line-speed and the number of bodies in the defensive line, by increasing the value of the kicking game to the attacking side.

There are three new areas of advantage for the attack:

1. GOAL-LINE DROP-OUT for held-up, knock-in in goal or forcing/grounding a ball which is kicking into in-goal. Reward defensive team with a drop-out anywhere on goal-line.

2. NO MARK IN 22M – for kicks which originate in attacking 22m. The kick can be marked in goal. Restart with a 22m drop-out.

3. 50:22 AND 22:50 – reward indirect free-kicks to touch with the lineout throw.

The third change is probably the most significant of the three. If the attacking side can roll a kick into touch within the opposition 22 metre area from their own side of halfway, they are rewarded with the lineout throw where it would have previously have gone to the opposition.

Attacking chips within the defending 22 can no longer be defused by a ‘Mark’; restart drop-outs now occur from the goal-line, not the 22m line.

All of these changes encourage the team in possession to kick more in the opposition half of the field, because the potential rewards are greater: there is more chance of an attacking lineout throw, a turnover deep in the red zone, or a kick return beginning in the opposition half of the field.

In an era where defences will frequently build as many as 14 players into a field-wide wall across the pitch, as far out as 40-50m from their own goal-line, these changes are important. If taken on globally, they will persuade more teams to keep extra defenders in the backfield.

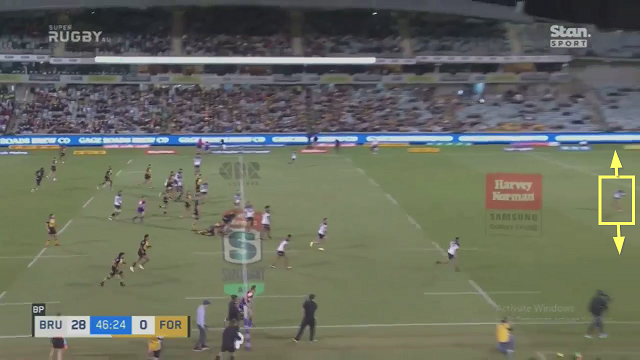

In Australia, where the trials have been running for two seasons, the 50:22 kick has proved much the most influential change. Here is one example from a game between the Western Force and the Brumbies:

The kick is made after four (unproductive) phases from a Force lineout by their number 10 (Jono Lance) at a time when the defence is trying to take the initiative by loading the line with 14 players. That leaves just one player manning the backfield:

The corners of the field are open for the kick from a midfield ruck, and because the kick rolls into touch within the defending 22, the Force keep the throw at the subsequent lineout.

Why is this important? An attacking ruck is frequently resourced by two or three players, so as many as four attackers (including the ball-carrier) can be absorbed at one breakdown, leaving only 11 available for the following phase. At the same time, defences very rarely commit more than the tackler ‘plus one’, giving them 12 defenders on the line. Advantage Defence!

The possibility of a 50:22 kick will make the 14-man line a much less attractive option:

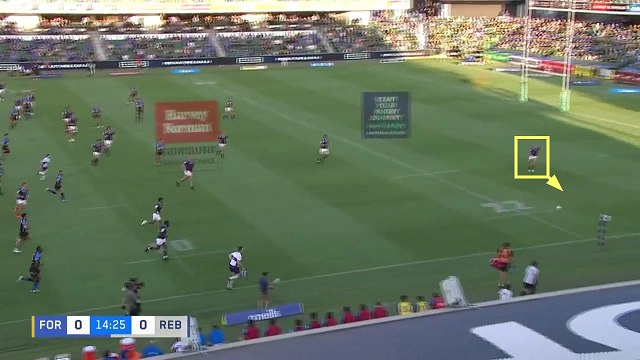

The Melbourne Rebels chase floods towards the line after a kick upfield, but the Force’s Rob Kearney is able hit the corner with a 50:22 which again exploits the single defender left in the backfield:

The answer for the defence is to keep a second player at the back, and that equalizes the numbers on the line. But it does not completely defuse the threat from the kicking game:

In this instance, there are two defenders back, and that cuts off the kick to the corner. But the possibility of a kick straight down the middle remains: a couple of rolls fewer, and the defence will have to touch the ball for a goal-line drop-out, and give the attacking side another crack from kick return.

The new trials laws are positive changes for the good health of the game as a whole. They will encourage attacking teams to use more variety, and explore the options offered by a constructive kicking game; while forcing defences to keep one or two more players in the backfield, and equalizing the numbers on the line. That can only be good for Rugby, as it emerges into the sunlight of the post-Covid era.