The kicking game in Rugby Union has been traditionally aimed at either the corners of the field, or straight up in the air. In the old amateur days, before the restriction on kicking straight into touch from outside the 22 was ever introduced, the main target area was beyond the side-line.

In “the match of a thousand lineouts” between Scotland and Wales in 1963, there were 111 examples of the eponymous set-piece occupying 38 of the 80 minutes of game-time. Wales won by six points to nil and the Welsh outside-half David Watkins only received two passes from his scrum-half in the entire game.

The other main target was the full-back, standing firm (or otherwise) under the celebrated ‘Garryowen’, with the high ball raining down on him from the skies and the hooves of stampeding forwards ringing in his ears.

Old habits die hard, not least in the kicking game. Newer rules, like the so-called 50/22, have made kicking for the corners more attractive than ever, even if the ball now needs to hit grass before it can cross into touch for the kicking side to gain their reward.

In this article four months ago https://www.therugbysite.com/blog/set-piece/what-is-the-theory-behind-restarts-up-the-middle , I illustrated the tendency to kick off towards the corners rather than up the middle with some accompanying stats:

“96% of restarts tended to be directed to the corners (zones 1,3,4 and 6), with a mere 4% down the middle of the field (zones 2 and 3). Those figures reflect the reality that kick-offs straight ‘down the pipe’ tend to be criminally undervalued, and hence under-used.”

In open play as well as from formal restarts, the kick straight up the middle is becoming an increasingly viable option for the side in possession. The main reason for this development is the patterns of defence adopted by the team without the ball.

In the red zone up 30 metres out from their own goal-line, the defensive side will often bring the full-back up into line early to secure the width of the field. Further upfield, splitting the field into two halves with a two-man backfield is now de rigeur, and those two defenders have moved wider to cover the threat of the 50/22.

Let’s look at the red zone first. With only 20 metres or so to play with, defences will tend to rotate the full-back into line very quickly, with the blind-side wing taking on his duties in an ‘accelerated pendulum’. This can create space for the short kick up the middle, splitting the two players. The following example comes from the 2020 Tri-Nations match between Australia and New Zealand:

The threat of all the Wallaby back three positioned beyond number 10 Reece Hodge to the wide side of the field, pulls New Zealand full-back Jordie Barrett across on to the end attacker early. That leaves the blind-side wing (number 14 Sevu Reece) struggling to make up ground in the middle.

Hodge’s kick hops up obligingly for Tom Banks in support, and Tom Wright steps Reece to convert the try. The space between the two backfield defenders is particularly obvious on the ‘Eagle’s Eye’ replay from above:

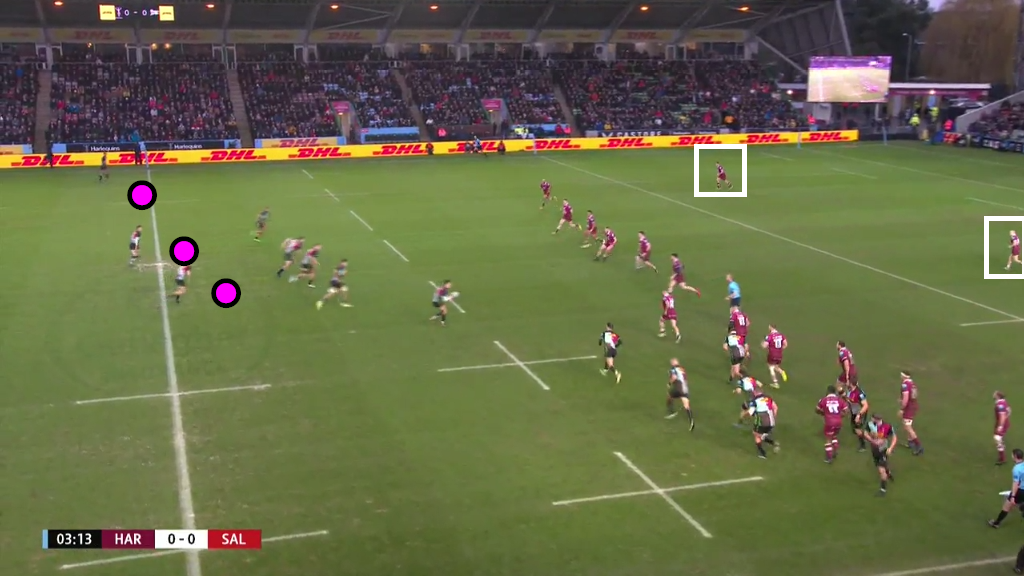

Even when the defence plays more conservatively, the middle remains an inviting target area. The following instance comes from the recent Gallagher Premiership match between Harlequins and the Sale Sharks:

The Sale full-back is standing deeper than Barrett and the spacing between the two backfield defenders is tighter, but there is still a major danger if the ball hits grass, with a handling error from Robert Du Preez trapping wing Tom O’Flaherty behind his own goal-line.

Further upfield, the defensive backfield duo have had to shift anywhere between five and 10 metres wider to cover the threat of 50/22 kicks and the turnover lineout which results from them:

These two examples come from the recent URC game between the Ospreys and Leinster, and both resulted in favourable outcomes for the kicking team (Leinster in white). In both cases there is a long upfield kick and a strong three or four-man chase pinning the backfield defence in its own 22. As I pointed out in the earlier article on restarts:

“What are the main benefits of restarting up the middle? Potential kickers are much further from the safety of touch, which means more passes need to be made, and more phases built in order to play out of the exit zone.”

The return involves a measure of risk associated with extra phases run inside the 22. At least one pass has to be made to take play closer to the safety of touch: in the first example the ball has to be taken up by the Ospreys number 8 forward and set a box-kick position just outside the 22 on the next phase, in the second there is an obvious forward pass out of the hand.

Chances are that you will win the territorial battle if the ball is kicked out immediately into touch from midfield:

Another long punt results in a small, but definite win for Leinster. The middle kick is made on the Leinster 40m line, and after the exit they have a prime lineout attacking position on the Ospreys 40m line.

Summary

There is still plenty of remnant thinking from the amateur era: that the kicking game needs to be directed towards, or across the side-line; or else, high up in the air to test the last defender. Some of the newer rules have encouraged diagonal kicking further, with the potential reward of a turnover lineout throw inside the opposing 22.

Kicking up the middle has a definite value with defences reacting ever more aggressively to threats on the edge, whether it is shorter attacking chips in the red zone or longer territory gainers further upfield. Split the middle and you will find a rich seam of gold.