The kicking game is here to stay. It has already happened in Rugby League, even though there is more space in which to attack with two fewer players on the field than there are in Union.

As long ago as 2015, ex-Great Britain back-rower turned pundit Phil Clarke commented on the development of League on Sky Sports as follows:

“Most teams attempt to break through the opposition in a similar manner. The rules of the sport and the nature of the game limit the ways in which teams can strike, and as a result we’re starting to see a similarity in the way that teams attack…

“Nowadays, the most important skill is the kick. Whether you like it or not, kicking the ball has the biggest effect on the outcome of the game. When a team gets towards the end of their six tackles, more often than not they choose to put boot to ball. Sometimes this is to simply put as much distance as possible from their own try-line.

More significantly, it’s the outcome of the attacking kicks that matter, and it’s becoming so important that a team’s season and a coach’s career can depend on it.

The improvement by teams in reading the attacking plays of their opponents means that they’re declining more running plays. However, defending against kicks is a bit harder to do.” https://www.skysports.com/rugby-league/news/12204/9795331/phil-clarke-the-kick-has-become-the-most-important-skill-in-rugby-league

Now elite level Rugby is moving in the same direction, and with stacked 13- or 14-man defensive lines the importance of kicking as part of the attacking plan is becoming more heavily accented than ever. The number one ranked team in the world, France, won the 2022 Six Nations by making the most kicks per game, and having the least active time of possession of any side in the tournament. Les Bleus were also the only nation to average over 1,000 kicking metres per match.

In the professional game, as much creativity is poured into the kicking game as it is into the construction of back-line moves. Two of my most recent articles https://www.therugbysite.com/blog/attack/how-to-find-the-pressure-points-with-the-midfield-kicking-game and https://www.therugbysite.com/blog/kicking/how-to-use-the-left-footed-kicking-game-to-your-advantage examined how some of that energy is invested.

It can be invested by targeting specific defenders in the opposition backfield who may be vulnerable to aerial attack, or by use of a left-footed kicking game which can change the angles and coverage of the field. It is also increasingly being used as a primary weapon on the blind-side of attacks, when the opposition are down on numbers due to a yellow card.

There is temptation to attack with ball in hand when you are one man (or woman) up, but in fact that tends to play into the hands of an undermanned defence. It is more precise to identify where the opposition has left a hole, and attack it with the kicking game.

There were a number of examples from the two Test series in Australia and New Zealand where the defensive side lost an outside back, and routinely left the blind-side wing vacant.

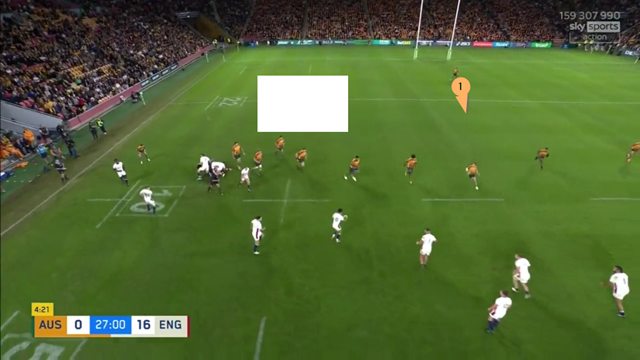

Let’s take a look at an example from the second game between Australia and England in Brisbane:

It is the first phase from lineout, and England number 10 Marcus Smith immediately looks to launch a kick against the grain, back towards the area behind the original lineout. Why?

The Wallaby right wing Izaia Perese is off the field on a yellow card, which leaves scrum-half Nic White struggling to fill in as an emergency defender in the sensitive zone behind the lineout. Australia are bundled back to their in-goal area as the pressure ramps up, and White’s clearance kick is returned all the way to the 5m line.

It was not the only time England essayed the same tactic with Perese off the paddock:

Once again, the Wallaby full-back is leaning towards the open-side of the pitch, and that creates space on the other side, even if the outcome (a line break for England) is slightly fortuitous.

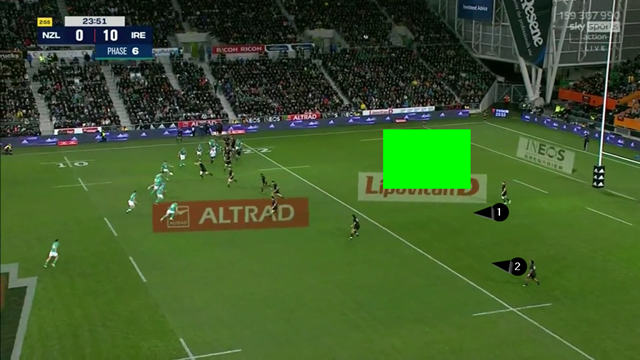

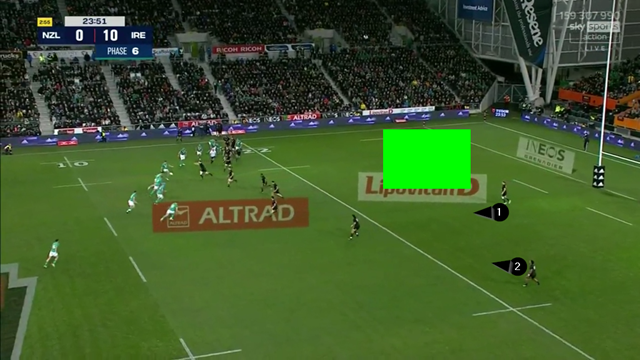

It was left to the best attacking side among all of the teams on tour in July, Ireland, to put the icing on top of the cake in the second Test against New Zealand at Dunedin. In this case, the All Blacks are missing left wing Leicester Fainga’anuku, and it is the blind-side wing spot which is left vacant on defence:

The Irish start from a lineout platform by moving the ball between their own left 15m line and the side-line. It is low-risk strategy, with forwards against forwards and the rucks in that area easy to cover.

Their real intentions become clear on 6th phase:

With number 14 Sevu Reece having moved over the left or open-side to replace Fainga’anuku, and number 15 Jordie Barrett sitting in centre-field, the blind-side ‘box’ opens up for the kick by Ireland’s Johnny Sexton.

Beauden Barrett’s exit created another big win for the men in green:

Ireland once again returns the kick down the short-side, and Ofa Tu’ungafasi is forced to make a desperate early tackle on Garry Ringrose in order to prevent a try being scored. That was another yellow card, and a potential penalty try.

Summary

It is easy to see ‘run’ rather than ‘kick’ when your opponent loses a player to the sin-bin, but the kick is often the better option. With many more defensive teams looking to rotate their backfield early, and bring their full-back up on the open-side edge to counter the use of the blind-side wing on attack, the reverse kick may well have more lead in its pencil in 15 v. 15 situations. Store it away in your memory, it could be important.