The pressure on the box-kick as a method of exiting from your own end is increasing all the time. Patience with the ‘caterpillar ruck’ is growing ever thinner. Those four or five layers of protection take so long to construct, and the half-back pours so much of his artistic soul into the careful rolling of the ball to the base – with a couple of head fakes to get the defence to jump across the offside line included, just for good measure.

First referees began to apply the five-second rule which had been previously adopted at scrum and maul more stringently. Here it is described by one of the top officials in the world, Wayne Barnes:

“As soon as the referee calls ‘Use it!’ that [kicking] team has five seconds to use the ball… The scrum-half can use his or her feet to move the ball back to the base of the ruck. If he or she doesn’t use the ball within five seconds, it is turnover ball.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ju8i6b6cKBo

More recently, they have started to demand that all forwards are fully bound to the ruck, and penalize half-backs for rolling the ball back with their hands instead of their feet. Hands in the ruck are after all, illegal, as every rugby-playing schoolboy, or girl, knows.

But the main sticking point is the sheer time it takes to form the dreaded ‘caterpillar’. As Harlequins and England prop Joe Marler put it eloquently in his five-point plan to improve rugby,

“The first thing I would do is ban the f***ing caterpillar ruck.

“It kills me. The whole thing is an a***. I would go as far as saying I’d ban box kicks but I might start to sound like Clive Woodward.

‘I want to see referees sanction the scrum-half for not using it when they shout “Use it”.”

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/rugbyunion/article-10343095/Joe-Marler-reveals-charge-including-promoting-Rassie-Erasmus.html

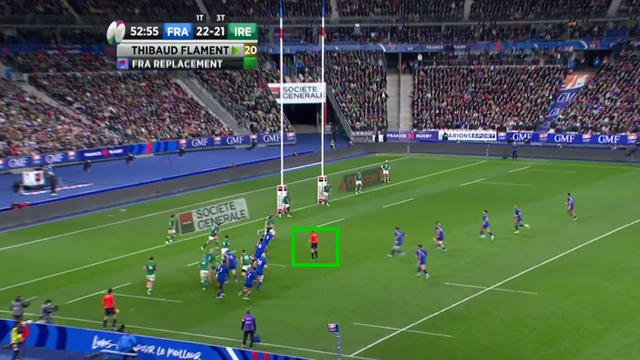

The pressure on the box-kick came to a head in the Six Nations game between France and Ireland. With the right boot of Johnny Sexton and the left foot of James Lowe both missing from the side which beat the All Blacks in November, Ireland were committed to using the box-kick off their number 9 Jamison Gibson-Park in the vast majority of exit situations.

France had clearly realized the opportunity presented in their preparation. Only one of Ireland’s first seven exits, up to the 54th minute of the game, enjoyed a positive outcome. France made hay, accruing no less than 21 of their 30 points from broken Irish exit plays. Only the arrival of the experienced Conor Murray off the bench stabilized that aspect of the game for the visitors.

France made a point of announcing that Jamison Gibson-Park would be placed under physical pressure from the very outset of the game:

It’s only a minor counter-ruck by France number 8 Greg Alldritt, but it upsets Gibson-Park’s balance by forcing him to momentarily commit to the melee. His kick spooned into touch only a few metres outside the Irish 22, and Les Bleus scored their first try of the match from the next lineout.

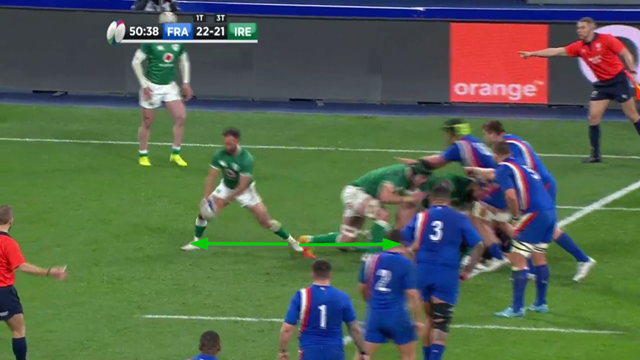

That sense of imminent pressure followed the Ireland number 9 around in exit situations to the very end of his involvement:

With the additional refereeing pressure on clearing the ball quickly, there has not been time for Ireland to build the caterpillar, and Gibson-Park is obviously wary of another attack around the base:

The kick is again short and hurried, and the outcome is a knock forward by the chaser, left wing Mack Hansen.

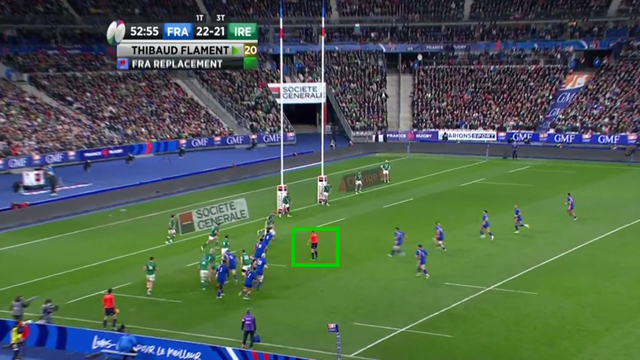

When the half-back has to take two big steps back from the ruck to create some breathing space from defensive pressure, it also creates problems of timing for the chaser:

Wing Andrew Conway is already a couple of metres ahead of the kicker as the box exit is made, and he is facing a ring of four French escorts before he can penetrate on to the ball. That represents a comprehensive defeat for the box kicking strategy.

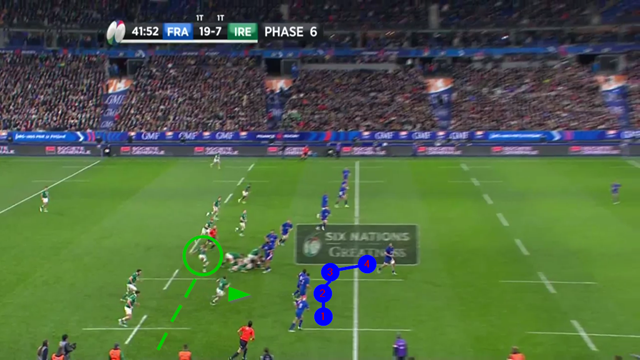

The other major conundrum Ireland struggled to resolve was one of position. France had identified the area from which the box kick would be made (just inside the near 15 metre line) and were prepared to contest heavily at any rucks set in this zone. Their efforts were rewarded by three turnovers:

In the first example, Ireland need one more ruck to get to the ideal area for the launch, and French wing Gabin Villiere is ready and waiting to pounce after the carry. In the second instance, Les Bleus know exactly where the run over the back of the lineout will come, and they are prepared to pour physical pressure at the tackle and post-tackle into that zone:

France converted the turnover into try on the following phase.

Summary

The Stade de France late on Saturday 12th February was a dark place to be for the future of the box kick. While it will continue to be one of an array of exit options, there is no doubt the kick off 9 is coming under increasing pressure from both opponents and officials. Demand to use the ball quickly and legally is in the refereeing spotlight, and the duress on the half-back at the base, and on any carries needed to get to the right spot is increasing. Variety on exits is becoming ‘the spice of life’.