The cross-fertilization of ideas between collision sports is on the increase. There are blocking techniques at the breakdown which resemble those used on the Offensive Line in American Football, there are ‘pick’ plays from Basketball that translate smoothly to the creation of kick return corridors in Rugby. Like Rugby, the NFL has moved to lower the height of tackles and avoid head-on-head contact, and it has consulted with prominent rugby coaches in order to achieve it.

Only a few months ago, Leinster Senior Coach Stuart Lancaster was asked by a well-known NFL coach how to stop the ‘Quarterback Sneak’ play close to the goal-line, which mimics the pick-and-go in rugby.

And so it goes on. Sports like American Football, Basketball, Rugby League and Rugby Union are in a constant state of conversation, one informing the other to the advantage of all.

Pass Protection in American Football is designed for the Offensive Line to shield the Quarterback who wants to throw the ball downfield. The five big guys in front of the QB have to buy him enough time to find a receiver, and complete the pass successfully.

The Offensive Line has to be able to hold off pass-rushers for roughly two and half seconds in order for the QB to get the ball away (the so-called ‘pass block win rate’), and they have to get their spacings right by creating a pocket of protection around him.

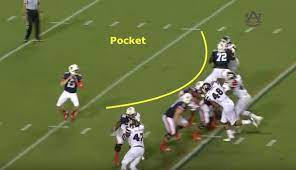

The ideal of ‘the Pocket’ is the shape of an inverted bowl, with the QB in the middle of it:

At the start of the play, the two Tackles (one on each edge) begin to turn out to force their opponents to take the widest route possible around them, and may drop back as much as 9-10 metres behind the original line-of-scrimmage as the play develops. The three interior linemen (the Center and two Guards) try to stay where they are without retreating more than a metre or two after the ‘snap’. The QB steps up into the pocket that has formed to make the throw.

This idea has passed successfully into Rugby, through the thinking behind the ‘escort service’ for receivers awaiting a box-kick by the opposing scrum-half. There are ever more contestable kicks at the professional level of the game, and all of the elements of the defence have to be able to work together to neutralize them – not just the catcher, but also the people running back into position ahead of him.

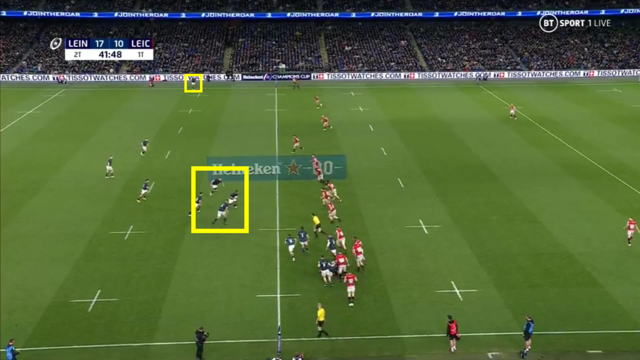

In the recent Heineken Champions Cup quarter-final between Leinster and Leicester, there were 14 contestable box-kicks, four launched by Leinster and 10 by their opponents. That represents one box-kick every six minutes. Leinster showed how to create a perfect pocket around the receiver early on in proceedings:

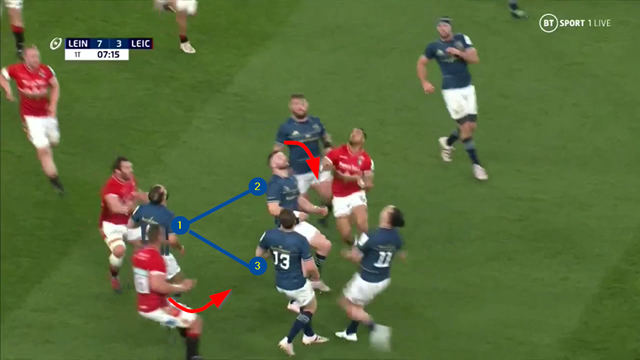

In both these examples from the first half, the Leinster left wing James Lowe is benefiting from the ideal three-man pocket of protection forming around him as the ball descends.

The two ‘tackles’ on each edge of the escort service (“2” Robbie Henshaw on the right and “3” Garry Ringrose on the left) drop back further than the man in the middle, “1” Jamison Gibson-Park. That means the two Leicester chasers who might either compete in the air, or make a punishing tackle on Lowe when he returns to earth (Antony Watson on the right of the picture, and Hanro Liebenberg on the left) have to go the long way around, on the outside of the play.

The potential jackler (Julián Montoya) has to make a tackle instead, and Lowe takes contact on his own terms. The same three defenders are involved in the second example, and Watson again cannot get near the ball in the air, nor can Montoya get into position to pilfer it on the ground.

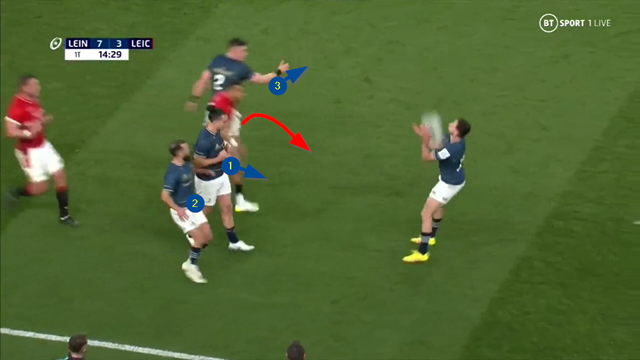

Now look at what happens when the three-man pocket does not form successfully around the catcher:

In this case, all three escorts are roughly level at the moment of the receipt and there is no pocket. Watson has penetrated in between Lowe and the man on his right, “2” Dan Sheehan., to make a tackle further downfield. The picture of Leinster’s attacking shape as the shot widens looks like this:

The near forward pod is in place but there are two players still running back into position from the Leicester side of the play, and there is no width out to the opposite side-line, so attacking options are restricted.

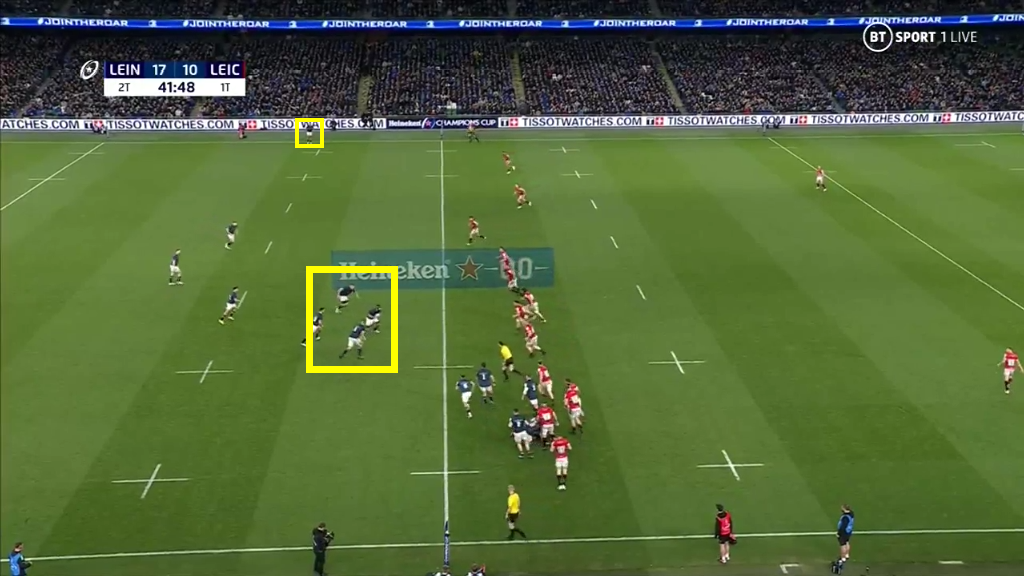

Compare that with the scenario when the pocket forms perfectly:

In this case, the desirable three-man ‘inverted bowl’ shape is present and correct, the receiver Jimmy O’Brien advances on to the ball unhindered and the ruck is quick and dynamic. The attacking formation immediately afterwards looks like this:

Everyone is onside for the next phase, and there is width available out to the left touch-line, enhancing the attacking options.

Summary

It is quite possible to ‘stand on the shoulders of giants’ by transferring I.P quickly from other collision sports like Basketball, League and American Football to Rugby. It took time for the theory of ‘pocket protection’ around the passer to evolve in Gridiron, but the lessons can be taken on quickly in Rugby and applied to the escort service surrounding a receiver of the high ball. When the meaning behind those lessons becomes ingrained, it not only simplifies the catch and the turnover of possession, it automatically creates the best scenario for a big counter-punch on the very next phase of attack.