The size requirements at the position of scrum-half have not changed between the amateur and professional eras. If anything, number 9’s have bucked the trend become smaller and more compact as the number of rucks has risen to the current average of between 150-200 per game.

Scrum-halves at a possession-based team like Leinster or Exeter can be expected to service over 95% of 100+ rucks per game, and that is just on attack. On defence, they can also be spotted in the ‘boot space’, filling in holes up the middle, and on either edge of the breakdown. The halfback is in thick of the action, whichever way you look at it.

A research article published by the University of Chester published back in 2012:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/231177090_The_movement_characteristics_of_English_Premiership_rugby_union_players

revealed that scrum-halves cover seven kilometres per game, more than any other positions. You can confidently add at least one or two more kms to that figure over the intervening 10 years.

Number 9’s are more often than not, the fittest blokes on the field. Ex-Hurricane Jamison Gibson-Park is now the premier half-back for Leinster and Ireland. As his old provincial coach at Taranaki, Colin Cooper observed:

“His conditioning is huge. He can run a 19/20 ‘yo-yo’ (22 metre shuttle sprints) which are now called broncos. If you’re reaching under 16 you’re too slow. Usually your front-rowers are around 16, and your backs and your fast boys get to 18, some maybe to 19. He recorded a 20.2 with us. I had two of them in the 20s, and he was one of them. He had a huge conditioning base. He’s also very quick and so his speed times were right up there – he had super speed times.”

For that reason, number 9’s tend to roll in at around 1.77m (5 feet 9 inches) in height (Gibson-Park is 1.75m) and anywhere between 79 and 84 kilos in weight (Gibson-Park is listed at 80 kgs).

There are one or two notable exceptions, like La Rochelle’s Tawera Kerr-Barlow (6’2” and 91 kilos) and Conor Murray at Munster (6’2” and 93 kilos). The bigger version of a number 9 still has a real part to play, if he or she can do the running required between rucks on both sides of the ball. A clue to the extra bonuses the over-sized scrum-half brings can be observed in Kerr-Barlow’s figures at ruck-time for his club. Over the first 21 rounds of play in the Top 14, he cleaned out at 54 breakdowns on offence and 22 on D.

The ability to play physically ‘straight up the pipe’ is fast becoming an important part of the number 9’s armoury. New Zealand has a shiny new home-based edition of the big 9 in the shape of Cam Roigard of the Hurricanes. T.J. Perenara’s successor at the Hurricanes is six feet tall and tips the scales at 90 kilos and he may yet become a fully-fledged All Black before this year’s World Cup.

Let’s take a snapshot of some of the reasons which make a bigger unit at number 9 more desirable:

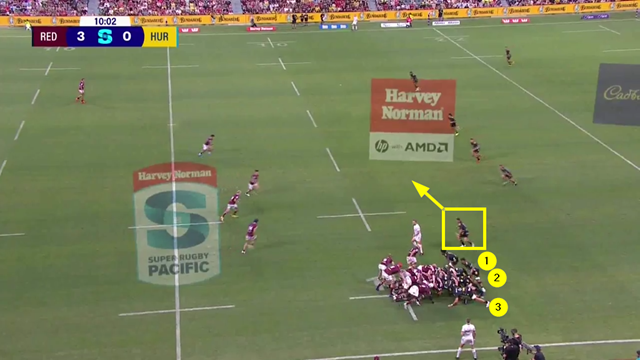

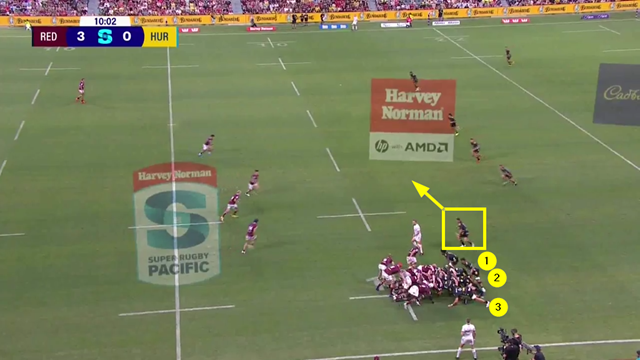

With quicker ruck resolutions under the new breakdown guidelines for referees, the scrum-half is frequently required to be an emergency safety option at ruck-time, able to move the pile when numbers are short. If, as a back, you are able to clean out a defending forward as definitively as Roigard in this example it will naturally open more holes up the middle, and preserve attacking momentum.

That strength can be just as valuable at defensive rucks:

If the new Super Rugby law-trial requiring scrum-halves to retire from the mid-point of the set-piece is adopted world-wide, it will have the effect of making them first man to the tackle ball, ahead of the three back-rowers. Roigard is already on-ball after the pick & go by Fraser McReight of the Reds (in the red-and-white hat) on the second play, then he goes again as the ruck begins to loosen up:

With the halfback positioned in the ‘sweeper’ role behind the ruck through phases, he or she will often drop back to cover shorter contestable kicks into the zone between the backfield and front line of defence:

The strength to stand in the follow-up tackle and deliver an offload once again greases the wheels on the counter.

In the traditional defensive sweeper role, extra strength can also be a valuable asset in disrupting attacking plays directed right ‘up the gut’:

Highlanders’ number 9 Folau Fakatava is indulging his signature move, running away flat from the base before flipping an inside pass behind his back to Jonah Lowe, but Roigard not only reads the play, he has the strength to wrestle the ball away from the Landers wingman and run the length of the field for a try on the counter.

Summary

All-World Frenchman Antoine Dupont has shown that strength really matters for the modern scrum-half. He or she not only needs to be a marathon runner from ruck to ruck, they also need the core strength to grapple and fight when they get there. There is still a place for the bigger man or woman at the spot, if they have the core skills. Cleaning out, pilfering on the deck and physical defence after the tackle are becoming important attributes. Who will forget Dupont’s tackle on Mack Hansen against Ireland, with the Irish wing hanging above the goal-line and poised to dot down?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YMdQR209sH8

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)