At the professional level of the game, many defensive coaches are also double-designated as counter-attack coaches. In other words, they don’t just deal with how to defend the opposition when they have the ball, they look at ways of managing the transition from a turnover of possession.

They examine the opportunities which might be on offer when they win the ball after the opponent has just had it.

Teams can go so far as to shape their entire attacking games around these moments. In the current Six Nations, France have enjoyed the least active time in possession of any side except Italy, at around 17 minutes per game. Yet they have won all of their four matches and are sitting pretty at the top of the table with only one round to go. If they beat England on 19 March, they will have won the Grand Slam for the first time in 12 years.

One of the keys to France’s change of attitude has been the appointment of Warren Gatland’s old defence coach with Wales and Wasps, Shaun Edwards with the national team. The ex-leaguer has an intimate understanding of how to link his defence to counter-attack, especially from kicks:

“It’s important to have a great kicking game and that was the first thing I spoke about with Fabian when I joined. When I was with Wales, we won a lot of close games with France because we had a better kicking game. If they had our kicking skills and options, they win.” https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/rugbyunion/article-9202809/SIR-CLIVE-WOODWARD-meets-France-coach-Shaun-Edwards-reveals-turned-England-role.html

After four rounds of the current Six Nations, nine out of France’s 14 tries have come by means of a kick, or a turnover return. None of them have taken more than five phases to convert.

France’s tense round three match against Wales in Cardiff put Shaun Edwards’ theory about the kicking game to the test, in an encounter containing no less than 69 kicks out of hand. France ‘won’ this aspect of the game by scoring the only try of the match after a long kicking duel.

The scoring sequence began with a long bout of ‘kick-tennis’ between the two backfields:

Number 10 Romain N’tamack kicks long to the Welsh 22m line, and Dan Biggar returns serve with a wobbly effort. There is already a small but significant difference when N’tamack launches his second kick of the sequence. Where he was putting boot to ball the 30 metres from the French goal-line, now he has advanced ten metres further upfield:

In games like table-tennis and badminton, there is an unwritten rule that the first player to ‘lift’ the ball – the one who can no longer keep the ball or shuttlecock on a flat plane – is on the receiving end of the rally, and more often than not loses the point.

In the second round of kicks, Welsh full-back Liam Williams is forced back deep into his own 22, and because he cannot find depth on the return, he has to lift the ball in the hope of making the kick contestable. Fatally, the ball travels too far in the air for the chase to close on the catcher.

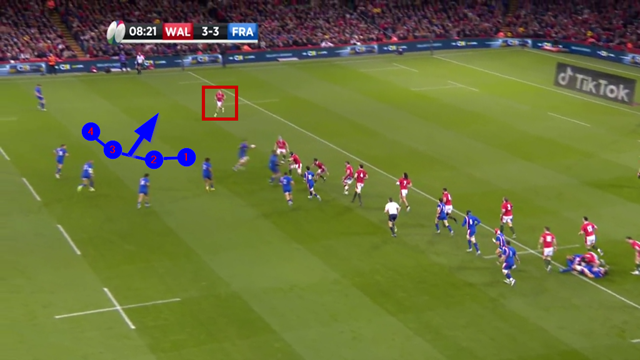

This is what France have been waiting for – the right opportunity to return a kick with ball in hand. The Wales right wing Alex Cuthbert has already had to do a lot of work off the ball, first running forward to pursue kicks, then dropping to rejoin his backfield on two separate occasions at the top of the screen. This is the area in which France choose to concentrate their counter-attack:

The France full-back Melvyn Jaminet penetrates the gap between Wales number 12 Jonathan Davies and Cuthbert, and the Welsh wing is (understandably) too slow on the turn to keep pace with his fresh French opponent, Gabin Villière.

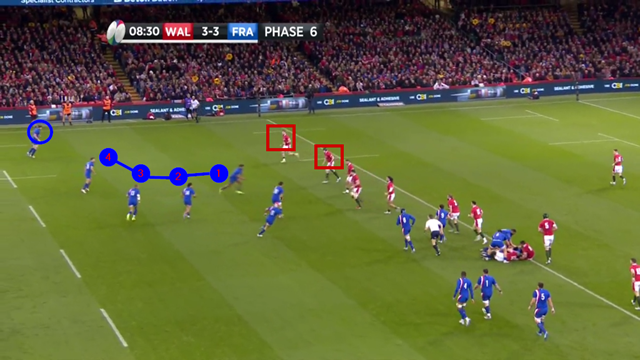

The remainder of the five-phase sequence is all about paring away Cuthbert’s inside support before attacking down his side once again:

The back inside Cuthbert (Davies) is forced to make a tackle in midfield on number 8 Greg Alldritt, and that reopens the old wound on the Welsh right, where Cuthbert looks increasingly isolated:

The Wales wing is on his own against four French backs, with number 7 Antony Jelonch providing width out to the left side-line. On the critical phase, Davies’ place has been filled by a forward (number 6 Seb Davies in the black hat), and the time for France to strike has finally arrived:

Davies and Cuthbert lose their co-ordination in defence of the French quintet, and Jelonch scores unopposed. The Welsh right wing must have been well and truly exhausted by all of the to-and-froing during the previous minute and a half!

Summary

Why is defence and the kicking game so important? Because it can lead to counter-attack opportunities set out clearly on your own terms. If you can dominate kicking duels and understand when the defensive ‘lift’ occurs, there will be a chance to counter against a chase fragmented by either a lack or organisation, or exhaustion, or both. You don’t always need the lion’s share of possession to construct an effective attacking game!

.jpg)

.jpg)