Getting around the ‘Rush’ Defence

One the most difficult problems for coaches to solve in the modern game is the rush defence. Rush defence dominated the recent series between South Africa and the British & Irish Lions, via the two versions coached by Steve Tandy (for the Lions) and Jaques Nienaber (for the Springboks).

Only six total tries were scored during the three games, and the Lions only managed two scores in the course of 240 minutes of play. Dating back to the knockout stages of the 2019 World Cup, Nienaber’s defence has proven especially resilient, giving up only three tries in the six most important matches in South Africa’s recent rugby history. All have been scored from start points only five metres from the Springbok goal-line.

One structural method of combating an effective rush defence is to employ a ‘single wing attack’. This means shifting the ball between one of the touchlines and midfield, and back again, in a zig-zag pattern. The width of the field is effectively shortened, with only one wing used for the attack.

Typically, a defence can only set up to rush on the wide side of the field. The numbers on the wide side are greater and there is more chance of a second pass being made. The single wing looks to avoid the possibility of fumble or interception arising from that scenario.

Let’s take a look at how the pattern can operate in practice. The following sequence comes from the first Bledisloe Cup match between Australia and New Zealand at Eden Park.

It lasts for one minute and 15 seconds (49:45-51:00 on the game clock) and 11 phases of play. Australia worked the ‘single wing’ productively for the first eight phases, moving the ball between the left side-line and midfield more than 30 metres downfield.

Between phases 9 to 11 the Wallabies attempted to use the wide side and (unsuccessfully) take on the All Blacks’ rush defence, with the sequence ending in an interception try for New Zealand number 10 Richie Mo’unga. It was an object lesson in risks and rewards attached to the different forms of attack available.

The sequence begins with a Wallaby kick receipt, and most of the Australian players clustered on the left side of the field after the first phase:

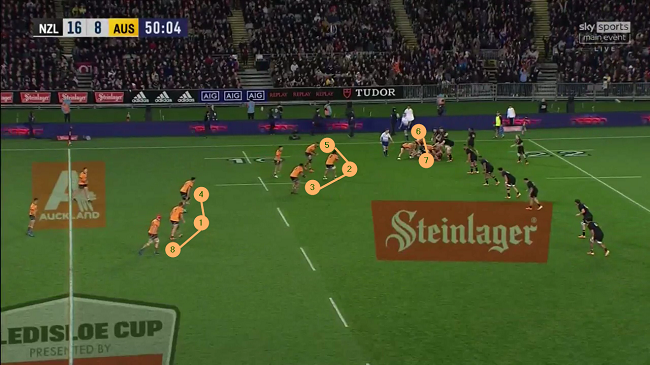

Only number 14 Jordan Petaia is left hugging the right touch-line, all the other Wallabies are over on the other side. Australia makes no attempt to move into a typically balanced attacking shape, like the 1-3-3-1, over the next couple of phases:

The two “1”s in the 1-3-3-1 would be usually be numbers 6 and 7 (Rob Valetini and Michael Hooper), but both remain over on the left side throughout the sequence, with the other two forward pods of three over-shifted in between the left touch and midfield. Only Petaia (out of shot) maintains width to the right. The attacking shape therefore, resembles more of a compressed 2-3-3.

That means the offence will zigzag between rucks set on the left side of the field.

Short ‘pop’ passes or offloads are at a premium in this form of attack – here, between Len Ikitau and Andrew Kellaway at 49:58, and Tate McDermott and Hooper at 50:28, and there is no opportunity for the defence to develop significant line-speed.

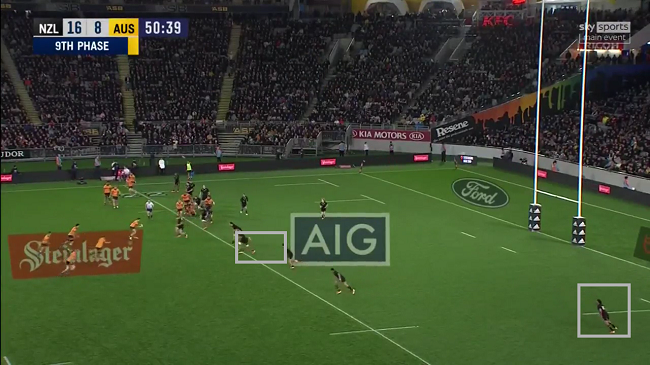

One of the keys in single wing attack is identifying the right moment to look for width on the other side of the pitch:

This is the moment of truth. There is an opportunity for either a short tip-on pass between Wallaby number 1 James Slipper and number 8 Harry Wilson (in the red hat), or a cross-kick to exploit the mismatch between Petaia and Mo’unga out on the far right.

In the event, Slipper cannot get the pass away in time, and on next phase the chance has evaporated:

Mo’unga has snuck up out of the backfield and into line in the interval, and he rushes the space between the passer (Hunter Paisami) and the receiver (Petaia) to make an intercept and score at the other end. It is a sobering lesson.

Constructing effective methods of attack to kick down the rush defence door remains a priority for coaches at every level of the game. The series between the Lions and South Africa (and the Springboks’ outstanding defensive record since the knockout stages of the 2019 World Cup) has reinforced that cold, hard reality.

Single wing attack, with all the forwards over-shifted into one side of the field, is a safe and effective counter. It is easier for the attack to control the ball in contact and defuse line-speed. The litmus test is the ability to time the change of direction, and identify the gaps on the wide side of the field accurately.

.jpg)

.jpg)