History brought up to date with the ‘Teabag’

The sole try the All Blacks managed in their winning 2011 World Cup final against France was called the ‘Teabag’. The genesis of the ‘Teabag’ lineout move was explained thus by Jerome Kaino, in 2015 autobiography:

Steve Hansen came up with it. He noticed that when the French defend from a lineout, no matter where they are on the field, they send most of their guys up as jumpers, and (Thierry) Dusautoir at the back stands off and attacks the opposition first-five if France don’t succeed in winning the ball. ‘Shag’ (Steve Hansen) says: Why don’t we send our two pods up for the ball, suck their guys in, and throw the ball from the top of the lineout down into the hole in the middle for Tony Woodcock to run through?

Steve Hansen had first picked up the ploy during his stint as head coach of Wales between 2002 and 2004. One of the regional sides in Wales, the Ospreys, used it regularly in their games during that period.

The main idea was to encourage the opposing lineout to split into two pods of three players (one jumper and two lifters) and then exploit the space by injecting a runner in between them. This also conveniently completes our picture of lineout attack against the defensive ‘joints’ in the last group of articles.

This is how the perfect Teabag worked for that All Blacks try in the 2011 final:

As one of the defenders targeted by the move (French captain Thierry Dusautoir) commented ruefully: “They scored a very nice try because they had carefully analysed our lineout interceptions on video, and then they scored a beautiful try.”

In the highlight clip, it is important that at least two All Blacks receivers draw their opponents into the belief that they are the real target for the throw. Thus, both Sam Whitelock at the front, and Kaino at the tail are airborne in order to condense the French pods around them.

When they return to earth at 3:03, it is likewise essential that they are on the inside of the intended play, screening off their opponents from getting to Woodcock with a tackle as he bursts up the middle. That is ‘allowable obstruction’.

With Thierry Dusautoir looking out ‘automatically’ towards Kiwi number 10 Dan Carter as his primary assignment, the road opens up for the All Blacks loose-head prop to curl around from the front of the lineout and canter through the middle for the score.

New Zealand had uncorked this move productively from time to time, as shown in this short video – first against the Wallabies in 2008, later against Wales (sic) in 2012:

Little refinements were added along the way, such as the Kiwi half-back moving around the end of the lineout to ensure the only possible defender was dragged out of the hole in the Welsh example.

In Wales, the move was augmented further by a change in the nominated ball-carrier. The Ospreys began experimenting with the use of their big running half-back Mike Phillips instead of a prop, which gave the move greater range than before. Instead of being restricted to close-range situations, the move became effective anywhere in the opposition last third of the field.

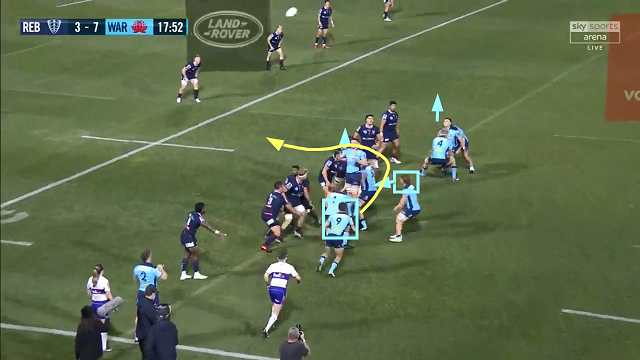

This is the state of the move now. The latest iteration occurred in the recent Super Rugby AU match between the Rebels and the Waratahs:

The new version of Teabag works with the scrum-half starting at the front of the line instead of a prop:

The number 9 is at the front with number 7 (Michael Hooper) at acting half-back, subtly drawing the front competition by moving towards the fake receiver.

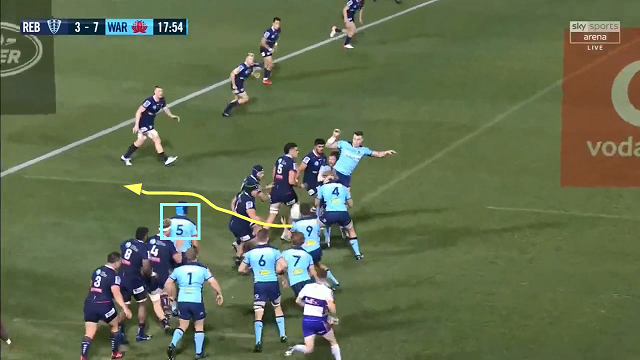

The big difference between the use of a halfback instead of a prop as the ball-carrier becomes evident as the move unfolds:

The Waratahs number 5 (Rob Simmons) ghosts across a likely tackling line at the front, but otherwise there are no defenders off the ground when the New South Wales halfback (Jake Gordon) hits the hole. With the scrum-half as the runner there is far more margin for error, and the move has much more scope and usability – the halfback will get through the hole much more quickly and be more of a threat after the break is made.

Whether you choose to attack around the ends of the lineout, through the middle or by moving the ball wide on 1st phase, there is ample room for creativity in designing ploys to exploit your opponent’s lineout defence. It is well worth the effort – just ask Steve Hansen.

.jpg)

.jpg)