If there was one message as dusk fell around a euphoria-laden Twickenham last Saturday, it was surely ‘Never trust the book-maker’. The bookies had installed Ireland as six-to-one on favourites in a two-horse race, which meant they were bound to come a cropper. Anyone with a smidgen of rugby nous would have rushed out to their local bookie to slap a tenner on England.

Whatever the bookies’ algorithm might have been saying, it could not measure factors such as Mindset or Attitude entering the arena. I wrote a preview article How England can Upset the Apple Cart which found that there were plenty of statistical ingredients already present on defence in a recipe for English success.

When Borthwick’s charges showed they were in the mood to add the exotic spice of Boldness to the mix, it became a potent brew indeed. Sir Graham Henry’s recurring mantra when he took over the reins as Wales coach in the late 1990’s was ‘Be Bold’. Hardly ever did a team meeting finish without that seminal phrase spilling forth from Kiwi lips. ‘Ted’ did not need the odds to be forever in his favour, he just required an even chance, with the right skill-set to exploit it.

Boldness builds belief more quickly than any other tool in the psychological box because it demands that individuals back themselves, and their skills, under the shadow of a real threat of failure. When they succeed, growth accrues quickly and immediately. Players learn how to play ‘in jeopardy’, how to sort the wheat [the bold] from the chaff [the reckless] in the risk-reward matrix.

England’s attack, which had flared into life only in brief snapshots in the previous three rounds, was transformed by boldness. The red rose offence found the right areas in which to embrace risk on its own terms consistently, with Steve Borthwick’s charges winning the line-break battle 8-2, while setting 84 rucks at a higher ratio of lightning-quick ball than their counterparts in green: 62% by England, compared to 55% by Ireland.

What is the new path that England are attempting to follow? Only five of England’s 16 attacking possessions ran over 4+ phases, and the men in white focused on the kick return as their chosen weapon of attack. They had six major kick return platforms in the game and made hay from all of them.

Bath inside centre Ollie Lawrence reinforced the point after the game when he said,

“Last week in training we worked a lot on our kick return and our counter-attack, which is an important element of our game, but we didn’t really show it against Scotland.

“It was a shift in mindset – let’s shift the ball and have a go at these teams because we’ve got such good players but we need to utilise them.

“We got the balance right against Ireland, that’s the reason we got the result we did.”

One of the primary planks in Ireland’s game-plan is their kicking game. Andy Farrell’s men like to kick long and infield to create high ball-in-play time rather than a staccato set-piece rhythm, and wing James Lowe’s left boot is highly instrumental in that process.

With the estimable Freddie Steward at full-back, England have tended to kick back rather than risk making a mistake in that no man’s land between the two 40m lines. With George Furbank at #15, Steve Borthwick swapped Leicester for Northampton and went against type as a coach.

Add Immanuel Feyi-Waboso and Tommy Freeman into the backfield mix and it was clear ‘Borthers’ had pushed his chips all-in on counter-attack with ball-in-hand, from positions on the field he would previously have considered either highly suspect, or speculative at best.

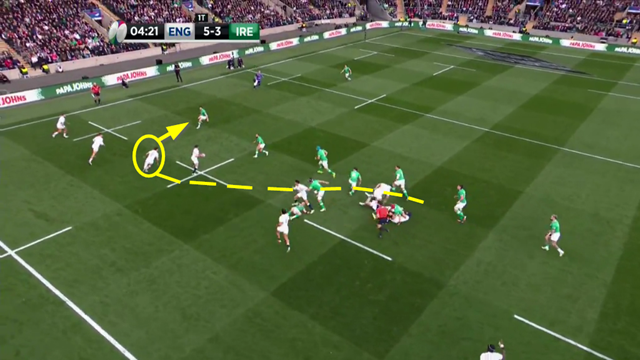

The new chord was struck as early as the 4th minute of proceedings:

Insert Furbank 1

If it was Steward forced to turn and chase back near his own 40m line off the long clearance by Lowe, there is little doubt the outcome would be a high kick and chase by the Tigers’ giant. But it is not the Leicester #15, it is the diminutive Saints-man Furbank, and he is prepared to be bold and back the skills of the England outside backs on the return with ball in hand.

His club-mate Tommy Freeman rides the hit from Calvin Nash in the first instance and that is risk-reward won. Furbank recycles himself from the far side of the ruck to become the key passer on the second play. Boldness is its own reward.

At the beginning of the second period, England converted their second try of the game after returning another infield exit by Jamison Gibson-Park from a position on halfway:

Insert Furbank 2

The moment of truth arrives for Ollie Lawrence when he is felled by the tackle of Hugo Keenan out on the right – just as it did for Tommy Freeman at the start of the match. With the Irish defence advancing upfield and minimal support around him, Lawrence is prepared to be bold, ride the challenge and wait for the cavalry [in the shape of Earl and Feyi-Waboso] to arrive. By next phase, he also knows that George Furbank will have found a way to recycle himself back into play after a heavy challenge by Robbie Henshaw in midfield, to lead the charge down the left.

Right to the very end, England were able neutralize the impact of James Lowe’s long left foot clearances by their boldness and determination to return with ball in hand across the halfway line:

Summary

There is no try on this occasion, but once again the pressure has been heaped high on the men in green, who find themselves under pressure deep in their own end.

Borthwick and his coaches hatched the plot and won the tactical battle against the Grand Slammers-elect. At the same time, Borthwick’s selection in the back three clearly announced a forward route for the national game in England. A combination of George Furbank, Tommy Freeman and Immanuel Feyi-Waboso are not going to spend their time kicking the ball back, they are primed to run for their lives. Embrace the risk-reward balance, be bold and let your skills do the talking.

.jpg)

.jpg)