How has the All Blacks attack changed since 2019?

After New Zealand’s two games in the knockout stages of the last World Cup in 2019, I wrote a couple of articles for The Rugby Site examining some crucial aspects of their attack structure: versus Ireland in the quarter-final, and England in the semi the following week.

That brace of articles looked at how the All Blacks tried to find width on the phases after the ball bounced back in off a side-line. They used two forward decoys coming close to the ruck off 9, with a full pod of three off 10.

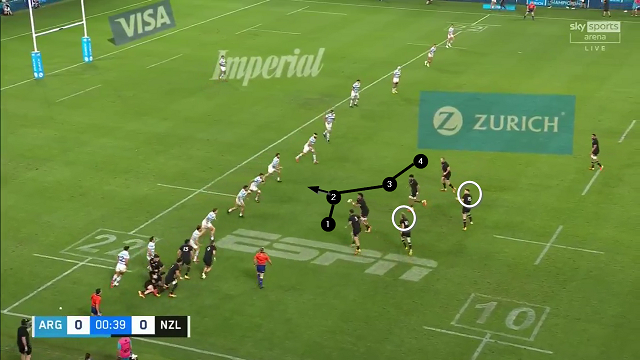

Against Ireland, the All Blacks successful bypassed the rush of the fourth defender to get the ball into the middle of the field:

The following weekend, England were well set up to defend this same attacking formation:

A lot has changed in the intervening couple of seasons since the World Cup in Japan, in particular the new breakdown guidelines issued by World Rugby in 2020 designed to speed up delivery of the ball from the ruck.

The speed of delivery means that there is much less time for both the attack and the defence to reorganize – and there are more dynamic, one-pass phases in and around the breakdown.

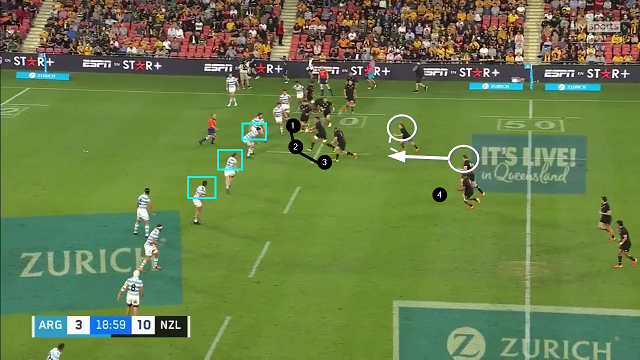

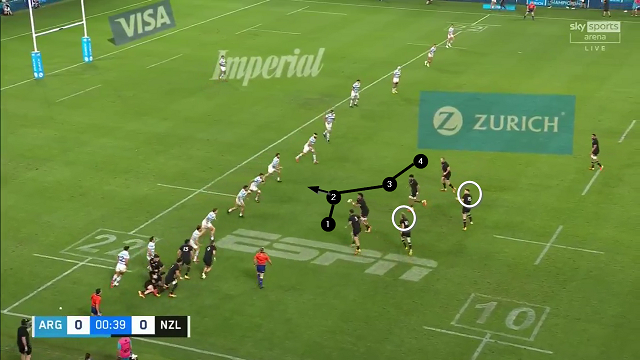

Take a look at the following sequence from the All Blacks’ recent Rugby Championship match against Argentina:

There are three rucks set in the space of less than 16 seconds and four phases of attack lasting 18’. Each breakdown produces lightning-quick ball of between 0-2 seconds and there are no passes made beyond first receiver. Something has to give, and in this case, it is the Pumas’ organisation around the ruck, allowing a clean break up the middle by number 8 Hoskins Sotutu.

So how does this impact the New Zealand attack structure when the ball is near a side-line, and the full width of the field is available?

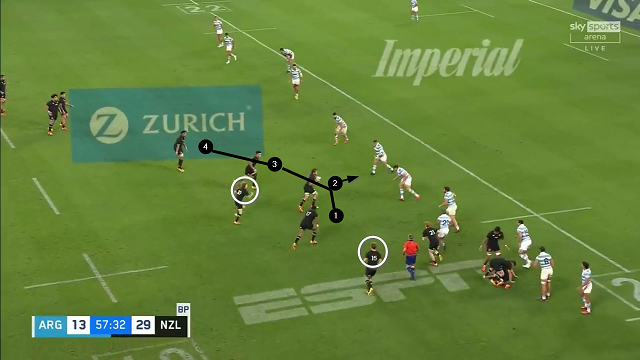

Instead of two decoy forwards off 9 and the full pod outside the number 10 in midfield, there are no less than four Kiwi forwards arranged close to the half-back:

The middle man of the pod has options both in and out, and the two main playmakers (10 Damian McKenzie and 15 Jordie Barrett) are aligned in close order directly behind him:

This is the same scenario on the other side of the field. Again, there are four forwards playing together with McKenzie and Barrett only a few short metres from the ball-carrier.

The idea is definitely not to move the ball into midfield from this formation. When the second pass is made, it typically features a short ball to Jordie Barrett coming back on an angle towards the first receiver, not away from him:

On this occasion, the ball is overcalled by McKenzie, but his only intent is to dump a pass of no more than half a metre off to the New Zealand number 15 on a cutback run, with the target area between the Pumas’ fourth and fifth defenders (both front row forwards) out from the ruck:

This type of play was a consistent theme. Here is Damian McKenzie coaxing Jordie Barrett on to another angled ball:

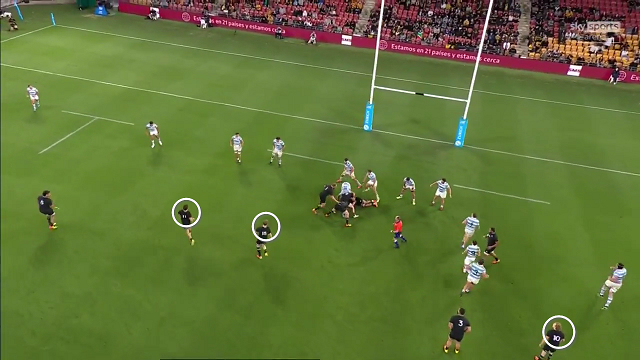

The effect of the quicker ruck-speed generated by the 2020 law variations has been to concentrate attack closer to site of the breakdown, with the wings and full-back spending much more of their time infield, looking for work directly off the halves:

In this screenshot, both number 11 George Bridge and 15 Barrett are aligned inside the first Kiwi forward to the left, with McKenzie providing an outlet on the other side.

If the game has progressed to the stage where you can win three mini-rucks in the span of only 16 seconds, it means that the time for re-alignment has been dramatically reduced – on both sides of the ball. There is generally less time to implement the old Canterbury Crusaders 2-4-2 pattern and spin the ball into midfield, so the All Blacks are looking to load up with an extra forward and an extra back three player close to the site of the ruck. It is an important glimpse of the future.

.jpg)

.jpg)