How the 1-4-4-4-1 can translate to professional level

Allan Pollock’s recent series on the 1-4-4-4-1 attacking pattern sounds great in theory. But how can the principles behind it translate to the all reaches of the game, professional and amateur?

Those principles could be summarized as follows:

• Strength of the offence is between the two 15 metre lines

• Three players available to cover the ruck at all times

• Pods of attackers play ‘without numbers on their backs’, mixing forwards and backs

• Two main receivers or ‘release’ players, plus halfback connecting the pods

• One attacker in each 15-5m corridor providing width

• Varying tempo between very fast (quick ball) and very slow (scanning defence for weaknesses)

A lot of these principles make sense in the modern game. As noted in my previous articles on The Rugby Site on Jack Nowell and Du’ Plessis Kirifi, there is an ever-increasing interchangeability between forward and back skill-sets; there is also a premium placed on ball control, which occurs primarily by condensing the attack between the two 15 metre lines. Ball-distributing ‘twins’ with number 10 type skill-sets are also popular, in order to connect the attacking pods and keep width in the attacking structure.

Perhaps the best illustration of how these principles might work out at the highest level of the game occurred in the group stage game between New Zealand and South Africa at the 2019 World Cup in Japan (25:05-26:55 in the first half).

Starting from the receipt of a South African kick-off deep in their own 22, the All Blacks built eight rucks with the sole interruption of a recovered Aaron Smith box-kick at 25:45. You can see the six phases after the kick, leading to a try for Scott Barrett in this highlight reel:

Many of the ‘rules’ for the 1-4-4-4-1 offence were in evidence.

• All eight rucks in the sequence were covered by three potential protectors or more – and three of breakdowns those were covered by four players. This ‘max protection’ was especially important as South Africa presents probably the strongest collective on-ball threat at the tackle in the Test arena. Even wide rucks were well-covered to both sides:

• The main ball-carriers in the wide channels were interchangeable – either Ardie Savea (number 6) or Sevu Reece (number 14) to the right, and Anton Lienert-Brown (number 13) or George Bridge (number 11) on the left. Lienert-Brown was twice the widest attacker on the left touchline and his final contribution was crucial to the score (at 2:45 on the reel).

• The two primary ‘Release’ players or distributors connecting the pods were number 10 Richie Mo’unga and number 15 Beauden Barrett, with occasional intervention by 12 Ryan Crotty. Barrett was the more prominent of the pair in this sequence, getting his hands on the ball four times at first receiver to Mo’unga’s twice. On three occasions Barrett ran the ball, fulfilling Allan Pollock’s default rule ‘if in doubt, carry – and carry hard’!

• The tempo of the attack slowed for the box-kick at the start of the highlight reel, which was preceded by a 12 second ruck. It increased dramatically in the final two rucks, with two immediate (two second) deliveries prefacing the Lienert-Brown break.

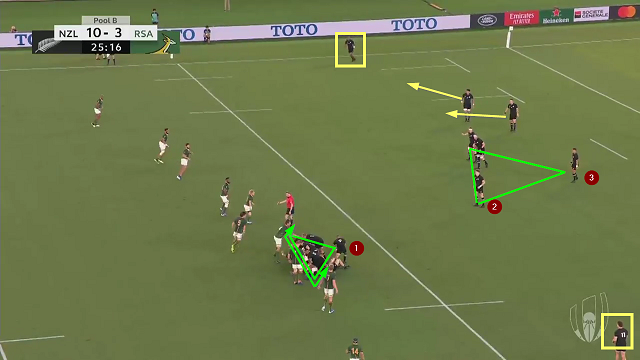

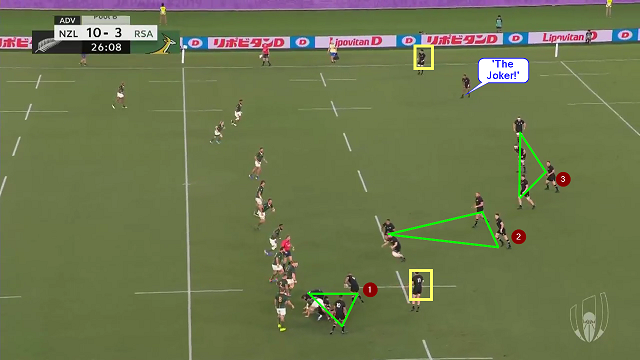

• The base structure of a 14441 was visible in the wide-angle shots immediately before and after one of the wide phase attacks:

In the first example, no less than six players (or two pods of three) have concentrated around the tackle area to ensure that there will be no possibility of a turnover. The halfback is at the base as “1”, with two release players (“2” Barrett and “3” Mo’unga) outside him. At the same time, there are still two attackers maintaining width (Reece and Bridge) to either side of the field. In this case the presence of an extra release player at second receiver allows the kick-pass across to Sevu Reece on the right.

In the second instance, with play further upfield there is less need to double down on protection and the pods are more widely spaced. There are three 3-man pods, each with its own dedicated release player, and two attackers providing the width (Bridge and Savea). The Joker is played by Sevu Reece who is spare on the right 15 metre line.

The 1-4-4-4-1 is an ambitious attacking pattern which wants to both have its cake and eat it. In order to make it work, you need a high proportion of forwards and backs who can exchange roles (especially among those who are required to provide width); at least three proficient receivers or release players, and top work rate from everyone in order to establish ‘max protection’ at every ruck, however wide on the breakdown it is set. Collectively, that is a tall order – but also an exciting challenge!

.jpg)

.jpg)