How the All Blacks are looking to beat the rush in Japan

The All Blacks attack coach is Ian Foster. At times during the media build-up to the quarter-final game against Ireland, ‘Fozzy’ looked to be feeling the pressure. He bristled when asked about the impact of Andy Farrell on opposition coaching staffs:

“Ian, what is it about Andy Farrell’s methods that make his teams successful against the All Blacks?”

“I don’t know, you’ve to ask Andy that…”

Farrell has been the defence coach on the staff of three different teams who have beaten New Zealand over the past seven years – with England in 2012, the British and Irish Lions in 2017, and Ireland in 2016 and 2018.

The Press questioning then shifted to the significance of Ireland’s November victory over the All Blacks in Dublin:

“I can’t remember it. No, that’s not true. We just got beat by a good Irish team. That was a different time, different place. Is it relevant? Perhaps, they would have learned some stuff, we learned some stuff."

“We actually don’t get too stuck in the past, it’s more about the challenge that’s in front of us. This is a World Cup knockout game and it’s actually about what happens this week, not what happened in the last two years.”

Ian Foster had a point to prove against an Andy Farrell coached defence, and to his credit, he proved it. Head coach Steve Hansen was keen to flag up the changes Foster had made to the Kiwi attack structure after the match had finished, 46-14 in New Zealand’s favour.

It is worth examining one essential element in those changes more carefully. Andy Farrell coaches a rush defence with high line-speed. The All Blacks like to use the full width of the field on attack, but have found difficulties in getting around that defensive pattern without the ball being choked off at midfield.

Against Ireland in Tokyo, the All Blacks showed how the ball could first be moved wide by the backs, and subsequent momentum be sustained by the forwards coming back in the opposite direction.

Moving the ball wide creates some inherent problem against a rush defence. Once the ball reaches the side-line, the defence is free to ‘tee off’ because it now has only one side of the field to defend. Therefore, whatever momentum has been built up on the initial phase by the attack often tends to be handed straight back to the defence on those following.

Let’s take a look at what this means in practice:

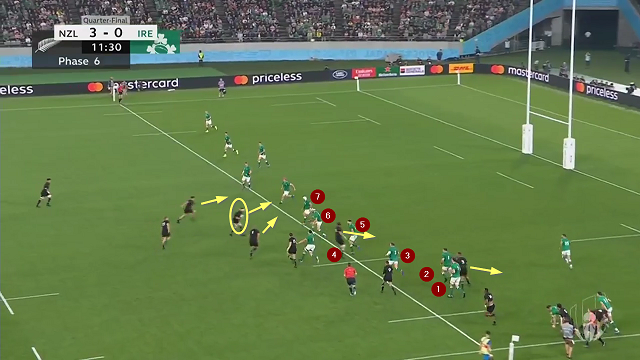

The ball has reached the right side-line and most of the New Zealand backs have been used up to get it there. Only Beauden Barrett and Jack Goodhue are available on the next ‘bounce-back’ phase, and the Irish are primed to rush off their fourth defender (C.J. Stander in the headband) out from the ruck:

Most attacking teams will accept that they have to set up a three-man forward pod and run straight into the rush directly off a pass from the scrum-half in this situation.

Not the All Blacks. They run two forward decoys inside (5 Sam Whitelock and 3 Nepo Laulala) while setting up their main pod off the number 10 or first receiver, in this instance Beauden Barrett. This involves a measure of risk: the passing has to be accurate to move the ball beyond the rush from the fourth Ireland defender, and into the more passive 5th-7th defender zone outside him. When they get there, Kieran Read is willing to bite off a little more risk by making the offload to the man outside him, Joe Moody.

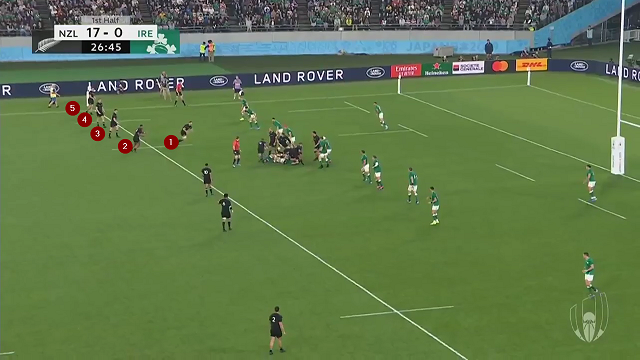

This set a pattern which the All Blacks followed successfully throughout the game. Here is a fuller version including the backs’ initial wide attack:

At the end of the backs play, all of Goodhue, Barrett, Sevu Reece and George Bridge have been consumed at the ruck, along with Aaron Smith passing from the base of it.

On the next bounce-back phase, they insert their number 10 (Richie Mo’unga) in between Smith and the forward pod, in order to get the ball beyond the fourth man rush (Rory Best in the white hat). A sharp tip-on pass from Brodie Retallick to his captain Read then hits the sensitive area between the 6th and 7th defender.

The All Blacks now have the advantage with the ball at midfield, and they are able to play out in either direction:

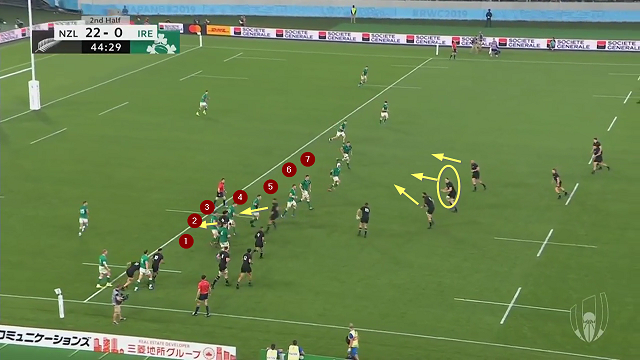

The same pattern was repeated with even greater success in the second period:

First the backs move, using the full width of the field from right to left. Then the risk/reward forward structure on the bounce-back phase, with two forwards running hard decoy angles and Barrett inserted between the scrum-half and the pod outside him.

Even though Ireland have adjusted to try and time their rush off the 7th defender (Best again in the white hat), he is still beaten by the accuracy of the pass across the front of Retallick and into the hands of Moody:

Ian Foster has certainly earned his corn as an attack coach at this World Cup, after experiencing a number of difficulties in combating Andy Farrell-coached defensive structures in previous seasons.

On Saturday, he has to prove he can handle another high-grade rush defence coached by one of his own countrymen, and an ex-All Black coach to boot in John Mitchell. It promises to be an intriguing contest, and one which may well decide the fate of the William Webb Ellis trophy in 2019.

.jpg)

.jpg)