How the exit kicking strategy has moved infield in the modern game

Wind the clock back to the amateur era – way back. In one game between Wales and Scotland in 1963, there were 111 lineouts. That statistic is approximately four to five times higher than the number of lineouts in the modern professional game.

The Welsh fly-half, the redoubtable Dai Watkins, commented ruefully that he had only touched the ball five times, “once to collect the Scottish kick-off, twice to pick up their grubbers ahead, and twice to catch passes thrown by my scrum-half”.

It is an indication of the weighting of the amateur rules towards set-piece and the kicking game. There were no restrictions on kicking directly to touch from any position on the field, and therefore even attackers as ingenious as Watkins did not always receive much ball from the half-back.

The automatic response to relieve pressure by kicking to touch, and starting from scratch with another set-piece, proved a difficult one to shake even in the early stages of the professional era. But as the game has become more sophisticated, more teams have realized the value of kicking infield.

Wherever possible, instead of seeking a pause in play with a clearing kick over the side-line, sides look for ways to gain positive momentum with the ball still on the paddock.

The basic aim for the defending team is to establish itself comfortably on the outer limit of its own exit zone – roughly 34 metres from its own goal-line. Once achieved, this position increases its range of options in the running and kicking games without increasing the risk that attends them.

Let’s offer some illustrations by examining a couple of examples from Super Rugby games played in Australia and New Zealand recently.

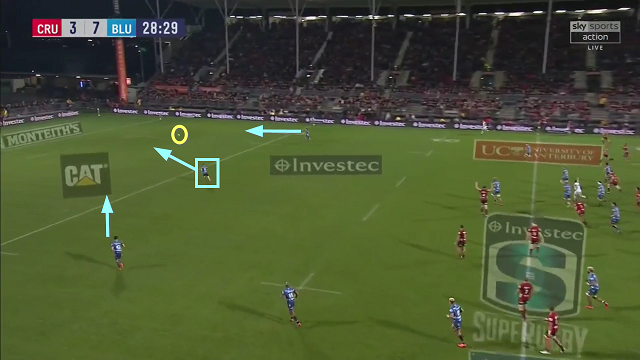

The following instance comes from the match between the Crusaders and the Blues in Super Rugby Aotearoa. It starts with a box kick by the Crusaders half-back Bryn Hall on the junction of his 22 and the left 15 metre line:

Hall ensures that the box kick does not go out over the side-line and that it is available for contest by the main chaser, left wing George Bridge. The ball travels no more than 13 metres forward in the air, but it takes the Crusaders out to that key marker where they have reached the boundary of their exit zone.

At this ‘marker’ the range of their decision-making increases dramatically. Part of the reason for that is the disorganisation that Bridge’s reclaim has caused in the Blues’ defensive ranks:

With Bridge’s opposite number Mark Telea involved in the contest for the ball in the air with his opposite number, there is a yawning space behind him which now has to be serviced by the Blues’ scrum-half Finlay Christie (sprinting back from the ruck), and the full-back Beauden Barrett (running laterally from centre field).

Barrett’s clearance can only be a defensive one with the extra time afforded to the Crusaders’ kick chase, and when they get the ball back the men in Red and Black are in prime position on the invisible edge of their own exit zone

Crusaders’ full-back David Havili has a choice of promising options. He can move the ball by hand out to his right or he can kick against another disorganized backfield.

He picks the second option:

It is easy for Havili to find space behind the Blues’ backfield because the main defender is none other than the number 9 Christie, who has had to run 80 metres towards his own posts over the course of two plays!

The outcome is just what the Crusaders want. The Blues are the team who have been forced to kick to touch to relieve pressure, giving the Crusaders a prime attacking lineout throw only 35 metres out from their opponents’ goal-line.

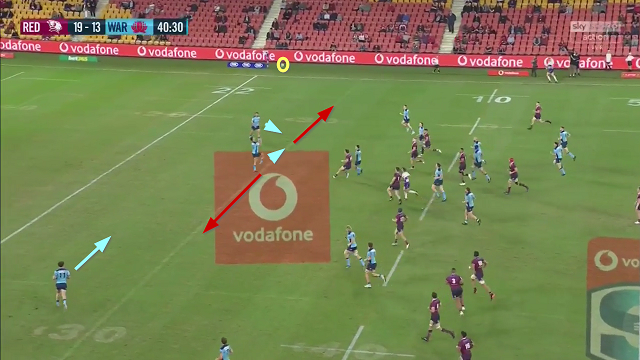

The second example comes from the Super Rugby Australia game between the Waratahs and the Reds. It starts with a long exit kick by Waratahs full-back Jack Maddocks from deep within his own 22:

Maddocks’ kick achieves very good length, over the Reds’ 40 metre line, and that give the Waratahs a chance to advance to the ‘marker’ on the edge of their own exit zone on the next play:

As the ball descends Maddocks is not under serious challenge in the air, and he has a support player (John Ramm to his left) available outside him:

The range of his decision-making has increased – if he makes this catch 20 metres further back. he will probably not choose to embrace high risk, and offload the ball to Ramm so close to his own goal-line. On the edge of his own exit zone, he can make a more positive decision, and Ramm duly takes the gap to make a clean break.

These two illustrations show how a top professional outfit will look to implement a more sophisticated exit strategy, one which does not involve kicking the ball straight into touch. With modern lineouts regularly running at a 90%+ retention rate, the rugby landscape has changed and giving the ball back to the opponent is not a desirable outcome.

Instead, a smart exit strategy will employ short infield kicks for repossession, or long kicks to outdistance the opposition backfield in order to work its way out to the invisible line where exit translates to attack, and more positive decision-making options become available.

.jpg)

.jpg)