How do we attack in the wide channels? What qualities do we expect from our wings and full-back? Back in 1971, the touring British & Irish Lions changed their hosts’ outlook on the game permanently. The Lions’ overlap play in attack, bringing legendary – and now sadly-departed – full-back J.P.R. Williams into the line as an extra man, brought sensational results, particularly in the provincial games.

The Lions’ philosophy was based on a core group of Welshmen, and you can see a perfect distillation in this try at the end of the Scotland-Wales game at Murrayfield in 1971:

There is crisp passing along the line, with the ball always thrown ahead of the receiver, and J.P.R enters the line to make the extra man, allowing his wing Gerald Davies a curving run to the corner.

Such moments tend to leave an indelible impression about <b.‘how to attack in the wide channels’, in the 15m-5m area. There remains much theoretical overhang from the amateur era, even though the Lions’ own visionary coach, Carwyn James was seeing the way forward very clearly indeed in his comments after the tour:

“The winger now has much more of a footballer’s game to play. He is no longer just as runner-in of tries… In so many situations now, he is the pivot of your attack and he becomes effectively your fly-half… Therefore, he must be a person who can pass the ball.

“We have always thought of wings as being runners-in, fleet-footed players who can tries but these days we expect far more from them. We expect some of the qualities of full-backs, we expect them in certain situations even to be distributors like a fly-half. The game is changing virtually every day.” We beat the All Blacks

Those are sage words. Roll the clock forward to the professional era, and the very best attacking teams in the world follow Carwyn James’ advice. They do not look to exploit overlaps directly, because they know how good professional defences are at closing down apparent space in the 15m-5m corridor and turning the tables on the offence. The attacking side needs more strings to its bow than simply taking extreme edges and finishing with pure speed.

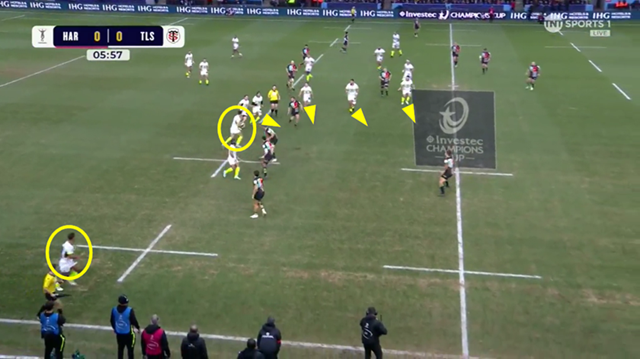

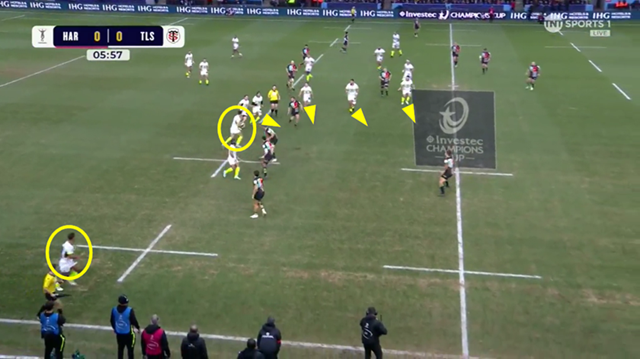

French club Toulouse are one of the elite attacking teams in Europe, and they often utilize apparent space in the 15m-5m zone as a ‘restart’ designed to create a killing zone elsewhere, via quick and decisive changes of direction. They used these switches to cut English Premiership club Harlequins to pieces in the group stage of the Champions Cup. The earliest hint came in the 6th minute of the match:

As soon as the ‘acting playmaker’ [Toulousain #12 Pita Ahki] hits the right 15m line, he is not looking to release the spare man on the right side-line with a long pass, but a group of support players on his inside with a short switch. This is where the French giants are looking to create a real breach in the Quins D.

The first proving occurred towards the end of the first period:

As play shifts towards the right touch, Toulouse have a temporary three-to-one overlap but they are not looking to finish down the side-line. As soon as the two acting playmakers – #15 Blair Kinghorn and #14 Dimitri Delibes – receive the ball, they want create play down that right 15m line, not finish on the edge. Kinghorn delivers the in-pass, Delibes switches inside and makes the try-assist for hooker Peato Mauvaka.

It is an organic part of Toulousain patience, their willingness to outwork their opponents in the attack-defence matrix:

There is plenty of space to work with down the left 15m-5m zone, but the acting playmaker, #13 Pierre-Louis Barassi, only wants to bring his left wing Matthis Lebel back on the switch and launch that man Mauvaka straight down the 15m line on the next play.

It looks like a nice opportunity to attack the last Quins edge defender with a potential 3-on-1 in view, but once again the Toulousain trained instinct shifts the ball to the support inside before realizing the apparent space with a concrete break down the left.

Summary

The Lions’ overlap play developed by Carwyn James on the 1971 tour only skimmed of the surface of the great coach’s thinking. He has already predicted a more far-reaching and complex role for outside attackers – not only wingmen – as playmakers more than 50 years ago.

The game is changing, day-by-day. The best attacking teams in the current era never take the apparent space they are offered on the edge without checking, or switching inside first. They bank on outworking their opponents to the 15m line and scoring closer to the posts instead!

.jpg)

.jpg)