How to attack with the box-kick

The perception of ‘negative play’ in rugby is often associated with kicking the ball. The implied criticism is there in the phrase ‘kicking the ball away’ – with the idea that a team which can no longer think of anything positive to do with the ball, kicks it away instead.

Rule changes in rugby have had the effect of reducing the amount of kicking in the game, for well over fifty years. All the way back in 1963, Wales and Scotland played out a famous Four Nations tournament match in which there were no less than 111 lineouts – about five times more than the modern average. Wales won the game by six points to nil, and the two scores were one penalty and one drop goal.

Clive Rowlands was the Welsh scrum-half that day, and he revelled in the law of the time which permitted unlimited kicking directly into touch. His outside-half David Watkins, one of the finest attacking talents of his generation, only touched the ball five times in the entire 80 minutes: “once to collect the Scottish kick-off, twice to pick up their grub-kicks ahead, and twice only to catch passes from my scrum-half”, as Watkins commented ruefully afterwards. Four years later he was playing Rugby League in the North of England.

That provided sufficient stimulus for the law to be changed, and thereafter kicks from outside the 22-metre zone which went straight into touch were no longer rewarded with a gain of territory. In 2008, the rule was extended further in scope, with teams unable to kick directly to touch when they moved the ball back into the 22 of their own volition.

The theme of reduced kicking to touch, and an increase in ball-in-play time have changed the complexion of the kicking game.The governing idea now is less to kick the ball away and create another stoppage, than to kick it to spots where you are confident you can either get it back, or force an error by your opponent.

As the current New Zealand number 10 Beauden Barrett says, “Kicking is definitely positive. It’s getting the ball to wherever the space is as quickly as possible… you just have to get the ball to where the space is.”

With a deluge of rain engulfing West London before kick-off in last Saturday’s game between England and the All Blacks, a quality kicking game was always likely to be at a premium. With four proficient kickers in their back-line ranks in the shape of scrum-half Ben Youngs, outside-half Owen Farrell, centre Henry Slade and full-back Elliott Daly, England were well-placed to exploit the conditions.

In the first half they were able to use an aggressive box kicking game off their number 9 Youngs to establish position and win the ball back on their own terms. Let’s examine three techniques they utilized to create pressure on the receiver, the New Zealand full-back Damien McKenzie.

England would have known that McKenzie is a dangerous counter-attacker given time and space in which to move, so the theme of longer box-kicks is to keep the delivery as close to the 5 metre line as possible, with a three-man chase blocking all of McKenzie’s outlets:

When McKenzie takes the ball on the left 5m line, right wing Chris Ashton is hugging the side-line, England’s best tackler (number 7 Sam Underhill) is directly ahead of him, with number 10 Owen Farrell blocking the channel infield.

There is nowhere for McKenzie to go, and the proximity to the side-line means that it is easy for Underhill to maintain outside leverage and drive him into touch after the receipt. That means an England throw to the lineout.

On shorter box-kicks, England showed excellent accuracy in their pursuit skills:

Once again, the two main chasers on the England right are Ashton and Underhill, but on this occasion the kick is approximately 10 metres shorter in length than the first example, and much further infield.

This gives Ashton the chance to challenge for the ball directly, and the technique he uses on chase is very instructive. This situation is one which has been fraught with danger for the chaser over the past couple of seasons: if he makes contact with the receiver by charging him in the air, or collides with him accidentally while looking back for the ball, the likely result is not only a penalty, it can easily be a carding offence.

Ashton’s solution to get to the target space ahead of McKenzie before the ball has finished its descent, and then ‘stop’. He is not charging the catcher and he is not running through him while he is still in the air, so the risk of penalty is minimized:

Ashton is competing for the ball but he is also making McKenzie go the long way around to get it – effectively McKenzie has to jump over the top of Ashton with little hope of coming back down on his feet.

In the event, the ball is dropped and picked up by Beauden Barrett in an offside position. That is a penalty to England.

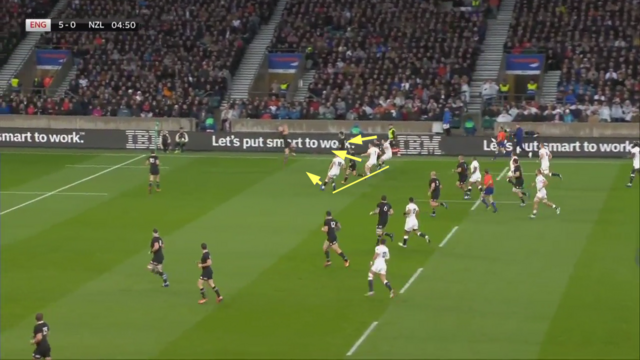

The third example illustrates the potential to win the ball back after a high kick by means of counter-ruck.

The kick is closer in length to the first than to the second of our two examples – not short enough for a direct contest to be made, but the ideal length for the defender to be able to control the receiver’s movements after he makes the catch.

Sam Underhill duly lines McKenzie up and makes an offensive tackle, driving the Kiwi number 15 five metres backwards in the follow-up. This opens up the possibility of a counter-ruck over the ball for the next three chasers, England tight forwards George Kruis and Ben Moon and number 14 Ashton. They can blow straight over the tackle, but on this occasion Underhill spoils the effect by trying to pick the ball up after the ruck has already been formed.

His mistake doesn’t dilute the educational impact of the three examples taken together, as a ‘handbook’ of box kick pursuit techniques. All three are positive in intent, attempts to recover the ball directly either before the receipt, or just after the catch has been made. It is kicking to create opportunity for the offence, rather than simply to move the ball off the field of play – illustrating just how far the sport has travelled from those 111 lineouts and that match back in 1963. It is indeed a different game.

.jpg)

.jpg)