How to chase the high kick – the Springbok way

It is often more difficult to spot innovation in a series of games where the pattern of play is both conservative and repetitive. That was certainly the case in the recent series between the British & Irish Lions and South Africa. As Sir Graham Henry so rightly commented, all three games were ‘a hard watch’ for the neutral observer.

There was a lot of kicking – an average of 54 kicks per game in open play across the series – and there were only six tries scored. All but two of those tries had start points deep inside the opposition 22 zone.

After the tour, the Lions head coach Warren Gatland justified the conservative style of play adopted by both sides as follows:

“The example of where the international game is at the moment is when we saw how South Africa won the World Cup, and they won through their kicking game.

And in 2019, during that whole year, the only team that they lost to were the All Blacks – and the All Blacks kicked more than South Africa. Every other team that they played and won they kicked more than the opposition, so that’s kind of where the game is at the moment.

It is about territory and kicking and putting kick pressure on, not playing too much rugby.

They don’t want lots of phases at breakdowns because every breakdown is a 12% chance of a turnover. You get to the next phase, it’s a 24% chance and the next phase is a 36% chance.

Those are the sorts of things and stats are people are looking at and you’re just limiting the percentages.”

How can the spirit of innovation be sustained with such a conservative mind-set dominating the play? The answer for South Africa relates to their work at the defensive breakdown and on kick chase.

South Africa tend to kick high in order to create an error in the receipt, or win the ball back themselves directly. One of the innovations they introduced in the first round of The Rugby Championship versus Argentina lay in the use of a second row (number 4 Eben Etzebeth) as one of the main chasers of the kick.

The aerial aspect of the game for a modern second row tends to be confined to the lineout and restarts, but Etzebeth’s exceptional work rate and energy level mean that he can fill the role on chase typically reserved for a back-rower or inside back.

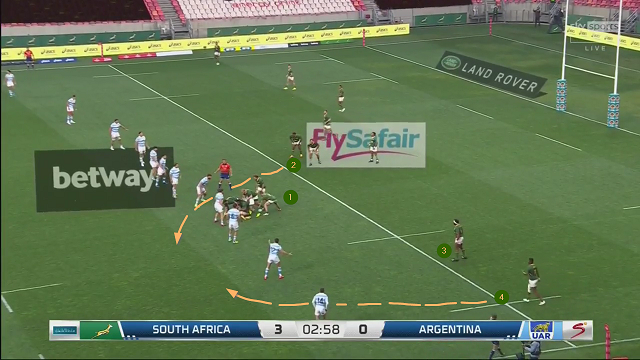

Against the Pumas, the Springbok set-up on chase for a box-kick off their number 9 Cobus Reinach looked like this:

Cobus Reinach (1) is the kicker, with two chasers on the short-side, Siya Kolisi (3) and left wing Aphelele Fassi (4). The main chaser on the right is Etzebeth (2).

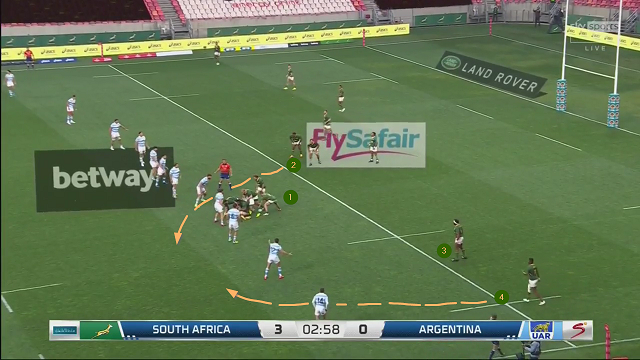

As the play develops, Etzebeth and Fassi converge on the target area from opposite sides in a pincer movement:

The effectiveness of this arrangement became more and more clear with every repetition during the first half of the game:

On this occasion the kick from Reinach occurs on the other side of the field, with Etzebeth sliding around to the left to fulfil his role as the primary open-side chaser. At the critical moment, he and wing Sbu Nkosi arrive underneath the point of receipt simultaneously:

Both have achieved take-off well before their Puma opposites, and Nkosi reclaims the ball.

The same well-drilled pattern was executed on both sides of the field:

This time it is Etzebeth who gets first touch ahead of Fassi:

The Springboks are suddenly over halfway, on the back of the minimal risk represented by one short pass from Kolisi to hooker Joseph Dweba.

South Africa reaped the ultimate reward in the 18th minute of the first period:

On this occasion Etzebeth and Nkosi are both chasing from the same side of the field, and the second row’s exceptional size and handling ability allows him to dominate the airwaves. What happens next? No passing necessary!

Two kicks, one catch, one ruck and one pass are all it takes to move the ball 50 metres down the field and score a try, with risk reduced to an absolute minimum.

This is what Warren Gatland’s comment about ‘limiting the percentages’ really means. Wherever possible, you move the ball North-South by kicking it, rather than passing it East-West across the width of the field and creating the opportunity for a turnover in contact. When you are fortunate enough to have a second row with Eben Etzebeth’s work rate and athletic ability in your team, it makes that choice a lot easier. It may not be pretty but it is effective, and it does allow for innovation within the game-plan.

.jpg)

.jpg)