How to create depth at attacking rucks

Depth is the key to several aspects of the game with ball in hand. One of my very first articles for The Rugby Site more than four years ago, was based around a Wayne Smith video session on support play.

In his session, ‘The Professor’ outlined his basic philosophy, with the ball-carrier getting on a straight line as swiftly as possible, and his support maintaining its depth approximately two to three metres behind the man with the ball.

Wayne Smith goes further, indicating that the support players should bend their runs into an “L” shape (first sideways – and maybe even a couple of steps backwards – and only then forwards) in order to ensure that they get in directly behind the ball and do not slide up alongside it.

The principles of depth and ‘verticality’ – support coming from behind, not alongside – can prove successful in every area of Rugby. For example, the most dominant driving mauls are associated with the creation of three or more layers of protection, sealing the opposition well away from the ball and allowing no interference as the ball is driven on.

The same principles hold true in contact situations after a tackle has been made. When a team wants to exit from its own end, how frequently do we now see this set-up?

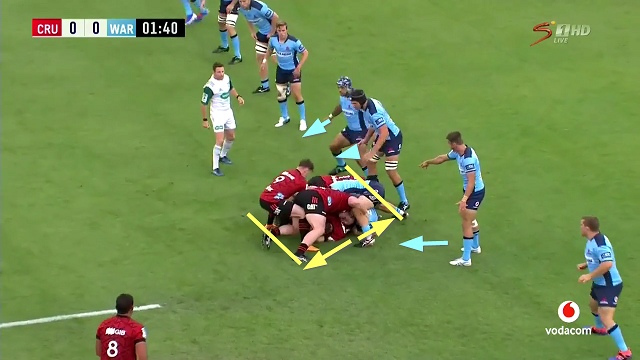

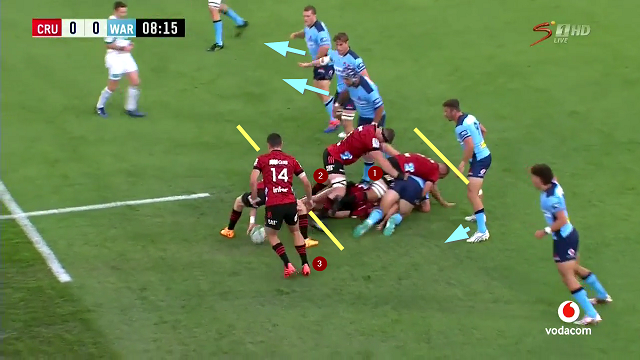

In this early example from the Crusaders-Waratahs match in Super Rugby 2020, the Crusaders build three layers of support on the kicking side for the exit from the boot of their half-back, Mitchell Drummond. The alignment of the forwards, one behind the other, ensures that Drummond will be in a comfortable ‘armchair’ and under no pressure when he goes to make the kick.

The same could not be said of some of the Crusaders’ attacking rucks in the first half. In this period the home team had a lot of difficulties countering the threat of the Waratahs’ hooker Robbie Abel on the ground after the tackle:

At most rucks, attacking teams will look to commit no more than two cleanout players in support. The first player looks to remove any threats to the ball as it is being placed, the second ‘sits and scans’ above it to create an offside line and protect the number 9 as he goes to play the ball.

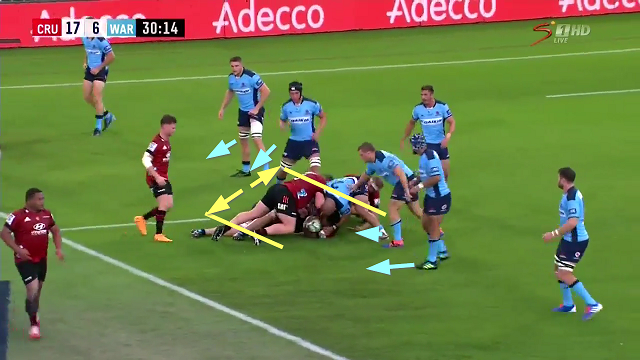

These instances represent three breakdowns where the cleanout support has failed to do its job properly and Abel has infiltrated on to the ball. The outcomes all have something in common:

• The rucks area all shallow, between one and two metres in depth

• The two cleanout players have finished side-by-side, rather than one behind the other

• The number 9 has been drawn into the ruck contest in two of the examples, making him vulnerable to disruption

• The interior defence is already ‘set’ and looking upfield.

The salient features of more successful rucks are the opposite of those above. Here is an improved version, even if it is not the finished article:

The ball-carrier (Andrew Makalio) receives the ball standing still, which means that the first two cleanout players (number 7 Tom Christie and number 3 Oli Jager) have to bend their support run into that “L” shape which Wayne Smith recommends:

They perform it accurately and the result is a good ‘save’, with Christie ahead and Jager directly in behind him at the end of the play. However, the ruck is still quite shallow, the defence is well set and Drummond is still relatively exposed at the base.

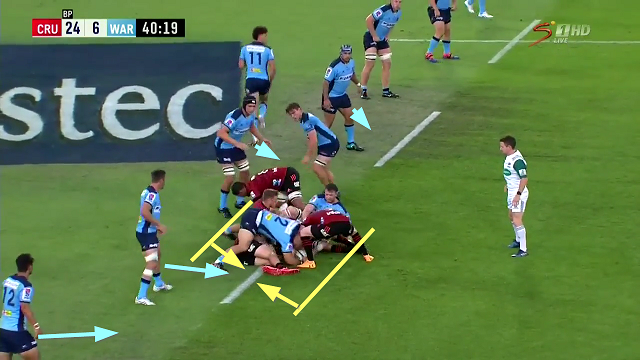

The following ruck represents another upward step on the ladder:

There is a little more depth, courtesy of a more dominant cleanout by the first support player, Drummond has more room at the base and some of the Waratahs defenders closest to the ruck are beginning to look and move outwards rather than straight forward.

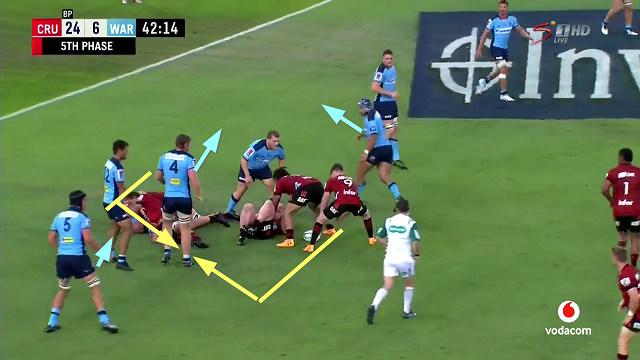

The longer the game wore, the more assertive the Crusaders play at the breakdown became:

Here is that man Abel again, but this time the Crusaders’ first two supports deal with him far more convincingly. Whatever momentum Jager lacks on the carry is amply supplied by the strength of number 4 Scott Barrett’s initial cleanout, and by the accuracy of number 8 Whetu Douglas, shuffling laterally to get in behind and finish Abel off, yards and yards downfield.

Now look at the situation which has been created:

The ruck is about four metres deep, and the Waratah’s inside D is a mess – three of the defenders are either looking or running sideways or backwards. It will not be easy for numbers 4 and 12 to get to the far side because of the mass of bodies on the ground. Mitch Drummond is back in his armchair and has an easy pass to make.

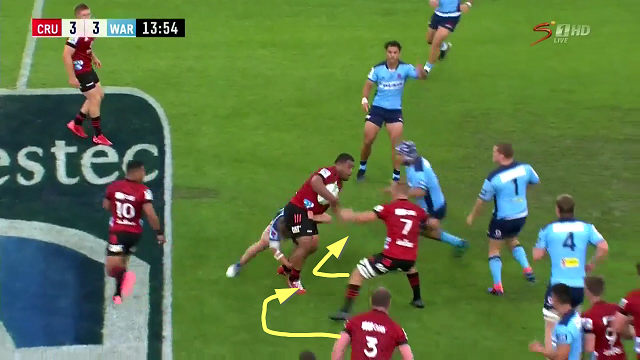

The same theme was reinforced late on in the game:

The carry is adequate but not dominant, and it is the excellent technique of the two cleanout players which creates the attacking opportunity for Richie Mo’unga to crosskick out to the left wing.

The same principles of depth and verticality apply everywhere on a rugby field. Correct alignment is as important at the cleanout as it is in support play, and you want your rucks as deep, not as wide as possible. Wayne Smith was right after all.

“The Rugby site is the only online coaching resource to offer a truly global perspective, subscribe for 12 months. ":http://www.therugbysite.com/pricing

.jpg)

.jpg)