“Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose”. Those were the words of French journalist and novelist Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr as long ago as January 1849, in his journal Les Guêpes (‘The Wasps’).

In English, the meaning of the proverb translates as ‘the more things change, the more they stay the same’. This is especially true of sports like rugby, where much of the innovation on view is very often an adaptation of what has gone before, seen in a slightly new and different light.

Coaches are constantly on the look-out for refinements of existing processes to make them more efficient, because the totally new, the ‘next big thing’ is much harder to find, let alone invent from scratch.

First-phase moves from lineout, or ‘gadget plays’ run within it, are a prime case in point. Much of what appears to be new, in fact belongs to the evolution of ideas over time, with coaches approaching the same concept from another angle.

The famous ‘Teabag’ move has now passed into legend, as New Zealand’s only try in the 2011 World Cup final, the first time that the All Blacks had won the William Webb Ellis trophy after a long drought of 24 years.

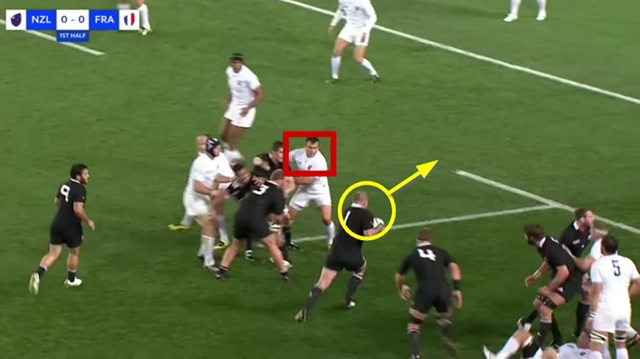

The score came from a short-range lineout near the France goal-line:

The attacking idea at this lineout had been brought back from Wales, where Sir Steve Hansen had been the head coach from 2002 to 2004. At the time, the aerial lineout contest on defence was popular in the Principality, with two boosters committing to form a three-man-pod and lift a counter-jumper in the air. When pursued too aggressively, with two pods launched skywards, this also create some yawning spaces within the lineout itself.

The ’three wise men’ in the All Blacks coaching staff had worked out that France would take exactly that aggressive stance, and had a plan to exploit it. It involved both Sam Whitelock (on a decoy at the front) and Jerome Kaino (receiving at the tail) getting up in the air to attract the counter-jump from their opposites. That committed six French forwards to either jumping or lifting, and levered the space through the middle like a tin-opener for prop Tony Woodcock on a peel from the front:

The one man who could have stopped Woodcock (prop Nicolas Mas) is committed as the inside lifter in the back pod and cannot lay a hand on his opposite number as ‘Woody’ gallops past.

As time went on the move was refined, with the scrum-half (big Mike Phillips) replacing the prop as the ball-carrier up the middle for both the Ospreys at provincial level, and Warren Gatland’s Wales national side. That gave the move greater range and allowed scoring finishes from much further upfield.

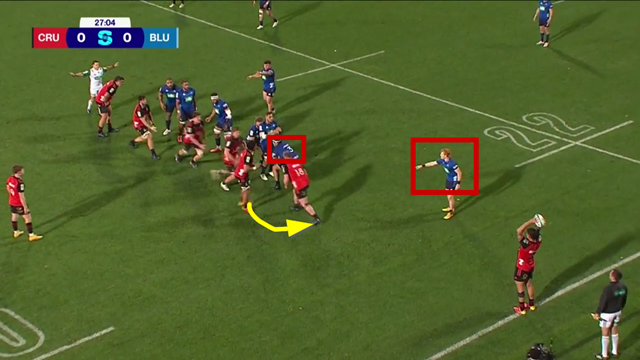

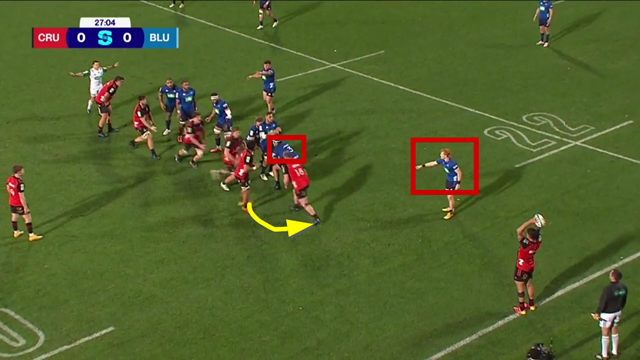

In recent times the same idea has been transferred from the middle to the front of the lineout, and we can evaluate two recent examples, one from each hemisphere. The first (negative) instance comes from the recent Super Rugby Pacific match between the Crusaders and the Blues:

The Crusaders use a decoy to draw Blues’ number 3 Marcel Renata to commit to the counter-jump, then have their number 6 Christian Lio-Willie pull out of the line to take the throw and spring hooker Codie Taylor down the right side-line:

Although Renata is taken out, the Blues’ scrum-half Finlay Christie is looking at the play as it develops throughout and shuts down both Lio-Willie and Taylor in the tram-lines.

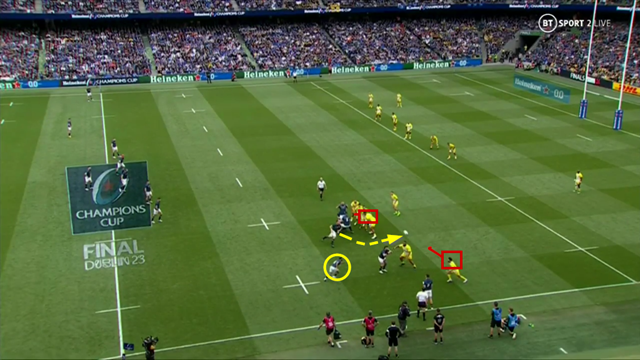

Leinster also used a variation of the same move at their first lineout of the game in the Heineken Champions Cup final against La Rochelle. The Stade Rochelais head coach Ronan O’Gara (who spent time as an assistant coach of the Crusaders in 2018-2019) attributed it to Andrew Goodman, a colleague of O’Gara’s on the coaching staff in Christchurch before he moved to the Irish champion province ahead of the 2022-23 season:

“[Our comeback was] incredibly good because we were on the ropes big time, we were being steamrolled by a very aggressive team. I knew [ex-Crusaders coach] Andrew Goodman would have a ‘special’ or two up his sleeve, but I didn’t expect it after 45 seconds.

“It was a great play they opened their batting with, 7-0, and then within six minutes it is 12-0 and within 11 minutes it is 17-0, so you are not long away from getting hosed which wasn’t the plan coming here.” https://www.rugbypass.com/news/ogara-were-seen-as-the-little-team-but-thats-about-to-change-la-rochelle/

Here is the new variant:

<p.

Why does the Leinster variation work, when the version run by the Crusaders doesn’t? There two major differences: firstly, the receiver (number 8 Jack Conan) is coming down on to the throw from number 3 in the line, with more momentum on to the ball than Lio-Willie; secondly, Leinster have spotted their own half-back (Jamison Gibson-Park) on the 5m line to draw the attention of the defender in the tram-lines (La Rochelle #10 Antoine Hastoy) and give their hooker Dan Sheehan a free run down the right side-line:

Once both the eyes of both the lifter (Will Skelton) and Hastoy are pulled inside, Sheehan’s has the speed and footwork of a centre to do the rest.

Summary

Innovation can be the genuine discovery of something completely new, but far more often it represents the improvement, or streamlining of something already known. The ‘Teabag’ lineout move has been in circulation for 20 years, but the ball-carrier and the target area has changed over time, improving both the range and potency of the ‘gadget play’ as a try-scoring weapon. That is how evolution really works.

.jpg)

.jpg)