How to expose the ‘spare man’ in defence

How do you recognize defensive tendencies? Is there a short-hand for understanding where a defence will be concentrating their strength on a particular play? The answer to both questions is ‘Yes’, and it revolves around the defensive use of the ‘spare man’.

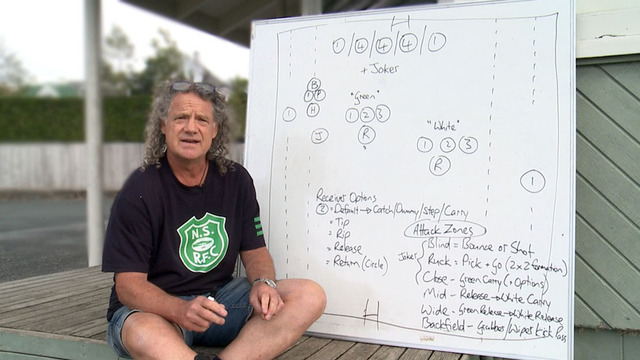

In 99% of situations which arise on a rugby field, the defence will be divided into two parts – a front line, and a backfield. The front line, which can number anywhere between 11 and 14 players, has to make first-up tackles against the running and passing games.

The backfield (typically between one and four players) is responsible for monitoring the kicking game, and plugging any breaches in the line which occur.

There is always a gap between the front line and the backfield, one which varies in depth, depending on field position. There is usually a defender who offers to fill the gap and connect the two lines of defence, and observing his movements can be key to the success of the attack.

In phase play, it is more often than not the defensive number 9 who connects the two lines. He can defend from behind the ruck in the so-called ‘boot’ space, and either move up into the front line anticipating the pass/run, or drop back towards the backfield in expectation of a kick.

The two lines of defence also exist from the primary set-piece in the modern game, the lineout. At lineout time, according to Law 18.35:

Players not participating in the lineout must remain at least 10 metres from the mark of touch on their own team’s side, or behind the goal line if this is nearer.

The spare man in defence at lineouts is the equivalent of the scrum-half, and he/she is called ‘the receiver’:

18.16. If a team elects to have a receiver, the receiver stands between the five-metre and the 15-metre lines, two metres away from their team-mates in the lineout.

It is the task of this player to connect the two lines of defence effectively and patrol that 10-metre gap enshrined in law. If the attacking side can accurately predict his/her movements, it will also know where the most vulnerable points in the defence are to be found.

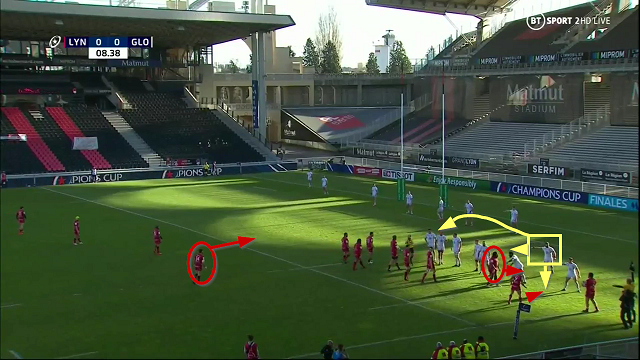

Let’s look at what this means in practice. Here are a couple of attacking lineouts from the same position on the field, from the recent European cup game between Lyon and Gloucester:

Lyon’s most potent forward ball-carrier (Matthieu Bastareaud, circled) has moved down to the front of the line, along with the attacking scrum-half.

The defensive receiver (Gloucester hooker James Hanson, in the yellow rectangle) is persuaded to shift down to mirror that movement. More typically, he would be patrolling the zone around the end of the lineout as the ‘tail-gunner’, able to connect immediately with the back-line behind him.

The play unfolded as follows:

It is a drop throw to Bastareaud at the front, which seems to confirm the rightness of Hanson’s placement. He is able to make the tackle on the big Lyon number 8.

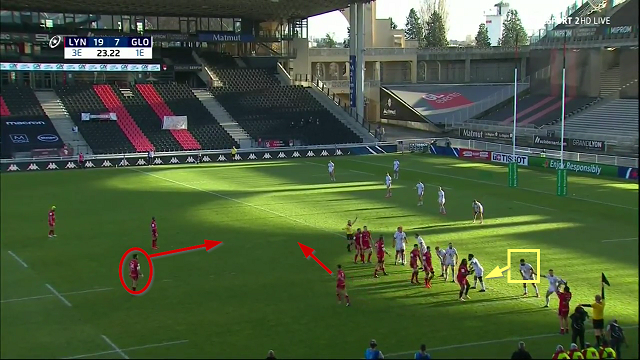

The next time this situation arose, the picture looked very similar:

Bastareaud is at the front again, and Hanson has moved even closer to the 5-metre line to mark him.

On this occasion however, Lyon are ready to spring a trap behind the same look. Having drawn away the spare defender from the end of the line, they are now in a position to use their own spare attacker (the blindside wing) in the vacant area between the defensive forwards and backs:

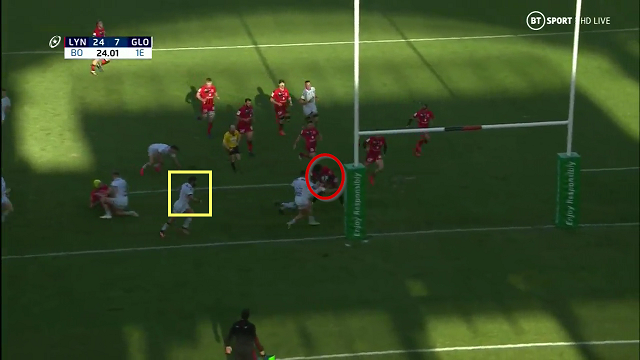

The defender who is left with the unequal task of tackling the Lyon number 14 is a tight-head prop, and there can be only one winner of that contest. The connection between the back-line and the forwards on defence has been irretrievably lost.

The shot from behind the posts provides another revealing illustration of how just how far the defensive receiver had been frozen out of the play:

With Bastareaud poised to score between the posts, the spare man who might have made a difference is still five metres adrift.

Locating the spare defender is the short-hand for deciding the direction of attack on the next play.

Whether it is pinning down the defensive half-back in phase play or the defensive receiver at lineout, once the spare man has been committed there will be an opportunity to exploit the connection between the two lines of defence elsewhere.

.jpg)

.jpg)