Coaches at all levels of the game, and in all sports are always looking for simple, robust solutions that work – the simpler, the better. One play, the eponymous ‘power sweep’ was the basis for the entire Green Bay Packers offence of the 1960’s, coached by its legendary mentor Vince Lombardi.

As the man himself once said,

"There is nothing spectacular about it. It is just a yard-gainer.

“But on that sideline, when the sweep starts to develop, you can hear those [defensive] linebackers and backs yelling, ‘Sweep!’ ‘Sweep!’ and almost see their eyes pop as those [offensive] guards turn upfield [and go] after them…

“It’s my number-one play because it requires all eleven men to play as one to make it succeed, and that’s what ‘team’ means."

Hall-of-Fame defensive tackle Merlin Olsen, of the Los Angeles Rams, once described what it was like to face the Packer sweep during a game:

“They ran the same play time after time after time. They had tremendous confidence in the play. They would make a call for a sweep to the right or a sweep to the left, and Bam! They had it. And they knew it."

Sound core plays like that are worth their weight in gold when the pressure comes on. You can then build variations off the base-play, and they will be just as reliable.

At the World Cup in France, one of the most effective and repeatable set-piece plays has involved the use of the #12 as the key distributor, with a short ball to his centre partner providing the line-breaking ‘money-ball’. The play is relatively simple, but it is the work off the ball by the entire back-line which makes it so lethal.

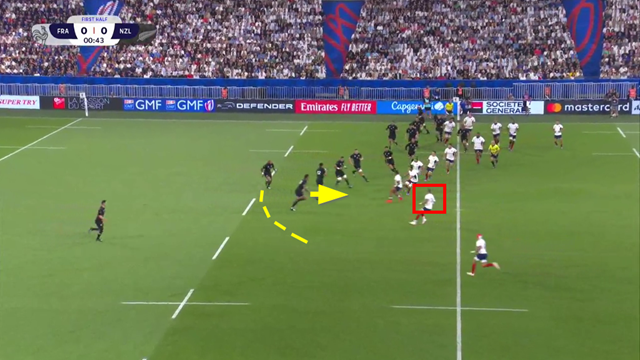

The first example occurred within two minutes of the tournament’s opening whistle, in the match between the All Blacks and hosts France:

From a lineout the ball is shipped to New Zealand #12 Anton Lienert-Brown, with two basic options around him: he can either feed an attacker swinging around the back (left wing Mark Telea, moving towards the far corner flag), or he can take the short option to fellow centre Rieko Ioane – very hard and very short.

The idea is to create indecision for the defensive #13 (Frenchman Gaël Fickou). Fickou chooses to drop off anticipating the ball behind, but that creates enough space for Ioane to burst through on the short option. The same play was repeated with surprising regularity and success in the pool stages of the competition:

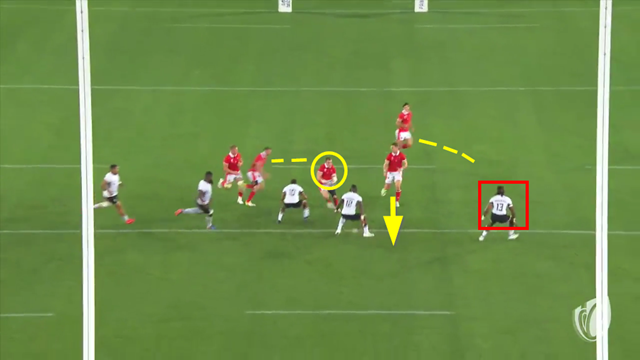

In this sequence, from the start of the game between Wales and Fiji, the men in red have added a few flourishes to add to the defensive hesitation of Fijian #13 Waisea Nayacalevu. The offside wing Louis Rees-Zammit is running the same ‘flag’ route as Telea, but Welsh #10 Dan Biggar is also doubling around inside centre Nick Tompkins to threaten a second touch. Once again, the simple solution takes all the chips, with Tompkins putting George North through the gap underneath the Fijian skipper.

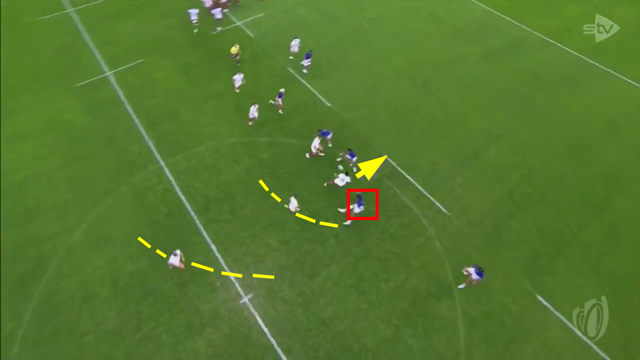

In their later pool game versus Australia, Wales added another twist to the tale. With the Wallabies looking to move over and cover the short ball, Wales introduced the in-pass off Tompkins to take advantage of the shift:

In all these cases, the offensive formation has enough variation to draw one-on-one tackles against powerful, dynamic attackers, and that is all that is needed to create the break(s).

The same play is just as viable off scrum as it is from lineout:

The Samoan #13 chooses to jump out on to the threat of England #10 George Ford doubling around his #12 Owen Farrell, and that creates the hole for the short ball, and a line-break for Manu Tuilagi, another very powerful runner who is quite capable of beating either arm tackles, or a defender in one-on-one situations.

Summary

Vince Lombardi’s power sweep was one single play with as many as 15 variations built around it, depending on how the defence reacted. Lombardi would have his offence run the play in all conditions and in every kind of weather against his first team defensive unit: ‘You can’t make the power sweep work when the defence knows it’s coming!’ might be one response. ‘Run it again’ would be Lombardi’s retort.

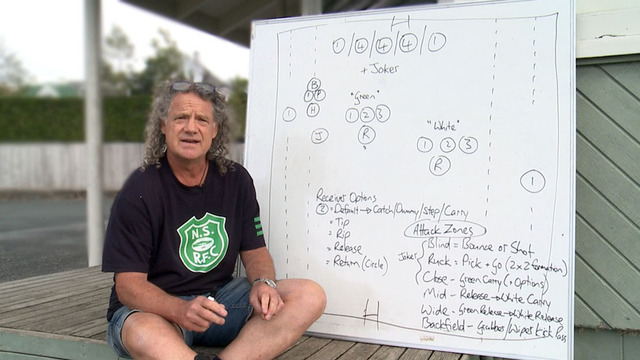

You don’t need quite as many variations on a rugby field – three or four would do – but you do need the same total confidence in your ability to make the base attacking play work. Once that is cemented in place, the rest will follow. Just keeping running it again, until it is second nature.

.jpg)

.jpg)