How to find mismatches against the single-line defence

Rugby is moving steadily towards League. Wales have recently won the 2019 Six Nations tournament on the back of a defence which conceded a mere 65 points, and only 7 tries over five games. That is a niggardly average of 13 points, and 1.4 tries per game – tournament-winning stats indeed.

The Welsh defensive coach is Shaun Edwards, the ex-Wigan halfback from League, and that is no coincidence either. Arguably the biggest change in Rugby’s professional era occurred when the game started to import defensive coaches from League.

John Muggleton in the Southern Hemisphere and Phil Larder in the North set the tone in the early part of that era. Muggleton (a former Leaguer for the Paramatta Eels and part of the triumphant 1982 Kangaroos touring side) coached an Australian D that gave up only one solitary try at the 1999 World Cup. Larder was probably the key figure in the English coaching group, building the white rose wall into a world-leading force before the World Cup four years later.

Coaches like Muggleton and Larder were game-changers, and their biggest single innovation was the concept of the single line of defence strung out across the entire width of the field, composed of both forwards and backs.

In the amateur era, forwards and backs had always tended to function as independent units. The forwards won the ball and the backs used it, and never the twain would meet. They even spent most of their training time working separately, with forwards delving the dark arts of scrum and lineout in one corner while the backs refined their moves in another part of the field.

All that changed with the introduction of coaches from League. Where forwards had always tended to hunt as a pack and follow the ball into contact situations as an eight, now they were required to ‘split and decide’ – either to commit to rucks or stand out, and become part of that single line of defence.

Roles began to blur, just as they had already blurred in League – where the positional interchangeability of backs and forwards was a far more common occurrence. The current Ireland defence coach Andy Farrell played international Rugby League in all three rows of the scrum and at outside-half!

The single line of defence places a premium on finding mismatches – pinpointing the weaker defenders and matching them up against your most potent attacking weapons.

Versatility on defence has spawned the same quality on attack in the modern era, with players required to fulfil multiple roles. In particular, wingers who were often seen as simply touch-line finishers in the amateur era, are now required to track down those weak defenders in the middle of the field.

In the English Premiership, the Exeter Chiefs are probably the most effective at using their wings on the inside track, often sliding them in between their three pods of forwards.

England star Jack Nowell provides some lucid examples of how wings and full-backs – and especially wings operating from the blind or back-side of the play – can become the most effective attackers.

Here are a couple of examples from a European Champions Cup match between Exeter and French Top 14 side Castres:

On both occasions, Nowell has come inside to play half-back at the base of the ruck. In the first instance, he is matched up against a front-row forward at the side of the breakdown. When he breaks the first line, there is only one defender in front of him; as a back three ‘natural’ he has the foot-speed to out-distance the cover scrambling back off that single line of defence.

In the second instance, Nowell beats the prop nearest the breakdown and accelerates away from the other line defenders alongside him. He is able to run 25 metres downfield before the tackle is made deep in the Castres backfield.

Now let’s take a look in more detail at a kick return sequence from the Wales-France Six Nations game in Paris. In the 46th minute of the second half, Wales have moved the ball towards the left side-line via five straightforward phases:

In the top left-hand side of the screenshot is Josh Adams, the Wales left wing. As play begins to move in the opposite direction, Adams is not content to remain on his touch-line, but begins to move infield with the ball:

In both of these shots, Adams has moved to a position well outside the Welsh first receiver Gareth Anscombe, and beyond the first pod of three Welsh forwards. Meanwhile, hooker Ken Owens (circled at the top of the screen) has taken up Adams’ traditional role on the extreme left edge.

Effectively, Adams and Owens have exchanged assignments, and that is the way it stays. Wales are still keeping their width but they are also increasing the chance of finding a mismatch in the middle of the field.

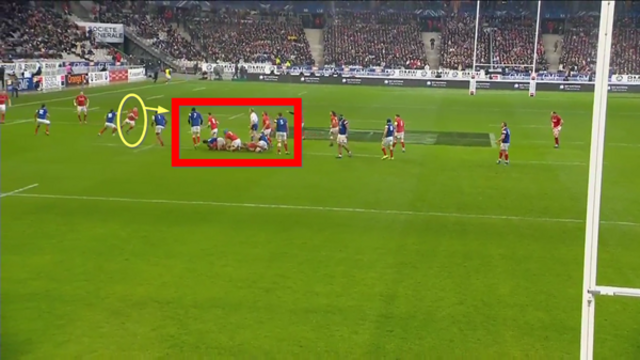

That mismatch duly arrives, and is quickly identified by Josh Adams on 10th phase:

Ball movement is still going right, towards the ‘wrong’ side-line, but Adams has inserted himself at first receiver beyond the right 15 metre line. His first step, inside off his right foot, leaves no doubt about his real attacking intentions.

He is heading back towards the site of the ruck, and the two guards (second row Paul Willemse and back-row Arthur Iturria) book-ending it. Adams’ combination of speed and power is more than enough to penetrate the gap, and with 13 defenders up or near the line it requires only one more pass to defeat the full-back.

The screenshot from the angle behind the posts at the moment Adams receives the ball is quite revealing:

The gap between #7 Iturria on the left of the collapsed ruck, and #5 Willemse on the right is at least five metres wide. Josh Adams’ body lean and first step is designed to do nothing other than exploit it. If it is a perfect example of how positional variations and flexibility can overcome a Rugby League style, single-line defence, it is also an eloquent statement of how far the professional game has moved from its amateur roots.

.jpg)

.jpg)