On 1 August 2021, World Rugby introduced some new trial laws to the game, designed to enhance the effectiveness of attacks by making the kicking game more important. Arguably the most important change was the introduction of the “50/22” kick.

One of the top referees in the world, Wayne Barnes explains the rationale behind the 50/22 in this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hFvq1NePPDE

To paraphrase his comments:

““If you kick the ball from your own half inside the opposition 22 metre line and the ball goes into touch, the kicking team gets the lineout.

“We all know that defensive teams can put a lot of pressure on the attacking side, often with 14 men in the line.

“What World Rugby and its law-makers are trying to encourage, is to make sure these defenders have to think twice. If the kick is made, they need to have someone back to defend it.

“Wingers now have to drop back to cover the kick, giving more space on the edges for team to attack.”

Eight months, it seems like a good moment to assess how the 50/22 is working out in practice. In particular, how can the kicking side identify the best scenarios from which to launch a 50/22 attempt?

There was a decent harvest of samples from both sides of the hemisphere divide on the weekend of 26th March. Three sequences from the Gallagher (English) Premiership in the north, and Super Rugby Pacific in the south, illustrated three very different situations where the 50/22 can be of concrete value.

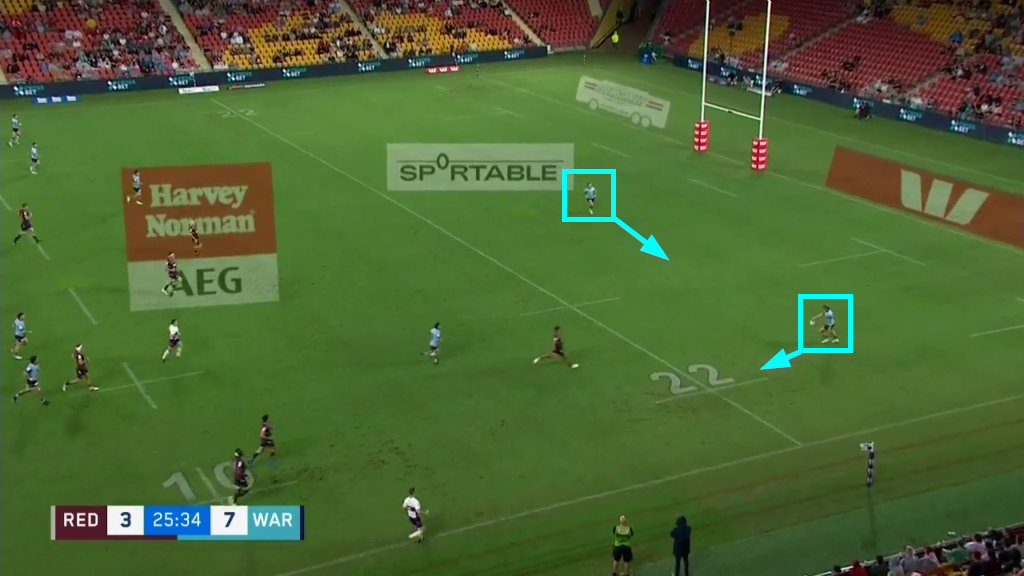

Let’s move to the southern hemisphere first, and the game between two Australian teams, the Queensland Reds and the New South Wales Waratahs. The following example showed how it is possible to manipulate a two-man backfield defence in order to open up an opportunity for the 50/22:

This is really a variation of the ‘wide-to-wide’ principle applied to the kicking game, rather than the running game. The initial punt by Queensland full-back Jordan Petaia is so steeply angled that it draws both of the NSW backfield defenders – catcher Tane Edmed and support Will Harrison – over to the left half of the field.

Edmed cannot risk a 50/22 and allow the ball to bounce, and Harrison has to follow him across to offer another option on the return. That opens up a huge space to the right for James O’Connor on the third ball, with Harrison scampering back desperately to cover the ground.

To recap Wayne Barnes’ comments, an accurate long kicking game can force the defending side to drop a third man into the backfield to cover both edges of the field. Two is not enough.

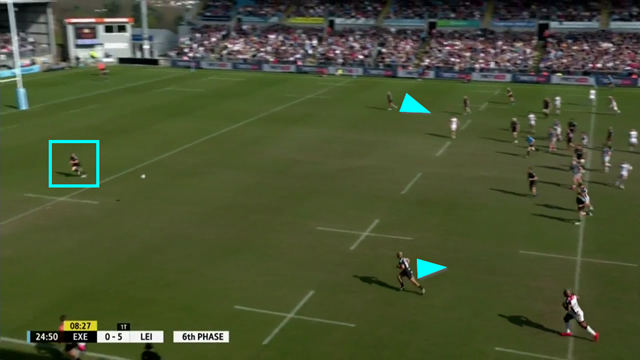

The other two examples occurred in the English Premiership game between Exeter Chiefs and Leicester Tigers. Exeter showed how a naturally left-sided kicker can open up the field for the long kicking game – especially from second receiver:

The intelligent construction of this exit play repays detailed study. Firstly, the Chiefs create the impression that they are going to box-kick off their number 9 down the right-hand side by building a ‘caterpillar’ of forwards. It draws the best Leicester aerial receiver (England full-back Freddie Steward) over to that side of the field as the catcher.

Instead, they make two passes out to the left and that is the second decoy. Whenever a defence reads the second pass in the opposition 22, it is the trigger for the wing to that side to think ‘run’ rather than ‘kick’, and in this instance Leicester’s Chris Ashton is pulled upfield, only to back-track once the kick is made by Henry Slade.

This is exactly the picture Exeter would have been hoping for. The wing (Ashton) is out of play, and the best backfield defender (Steward) is furthest from the ball. The ball can kick left into touch for the 50/22, or may even roll into the in-goal area for a goal-line dropout, and both of those would represent massive territorial wins for the Chiefs.

That pushes the returner (ex-Crusader Nemani Nadolo) into taking a risky option, moving the ball infield to Steward under pressure from a strong Exeter chase.

The third example comes from the same game, but with colours reversed:

This is an illustration of what tends to happen when the defence changes the momentum of a sequence when their opponent has the ball near the halfway line – either making a dominant tackle, counter-rucking strongly or in this case, blocking down an attacking kick.

When the defence scores s small victory in this kind of field position, it will tend to pull up the two wings into the 14-man line Wayne Barnes describes in his presentation. So, a broken play near halfway can provide an unexpected platform for the 50/22 kick.

In this instance, the Exeter wings both chase up automatically after George Ford’s kick is blocked, and that gives Ford a second bite at the cherry. He takes full advantage with the 50/22 to the unmanned corner.

Summary

The 50/22 kick is beginning to grow in value as the different scenarios in which it can be a weapon are recognised more clearly.

A two-man defensive backfield can be a vulnerable target when pulled first one way then the other, and a naturally left-footed kicker can greatly assist in the process of unpicking it.

Even broken plays which encourage the defensive wings to push further upfield can provide an unexpected springboard for the kick into a vacant corner of the 22.

There are ample opportunities for the ideas behind the law change to come to fruition.

.jpg)

.jpg)