The new breakdown guidelines issued back in June 2020 – you can see an expert summary by New Zealand Rugby Referees Manager Bryce Lawrence and international official Paul Williams here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PPS9Z5hzPPw – were intended to make the game less of a grind.

The idea was to quicken up ball either recycled or stolen from the ruck, by removing the tackler earlier in the contest, and by demanding that players from both sides stayed on their feet for longer. The advantage was typically shifted towards the attacking side, which could now generate a succession of one or two second rucks and stress the defence with ‘lightning-quick ball’.

For a while, it worked. Harlequins won the English Premiership in a 78-point, 11-try festival of open rugby against the Exeter Chiefs in the Spring of 2021. This season, teams have already adapted and all of the major finals – in Super Rugby Pacific, the European Champions Cup and the Gallagher Premiership – have been played out on terms dictated by the defence.

The climax was reached in the English Premiership final between Leicester Tigers and Saracens, the two masterminds of the kick-pressure game. The match featured a colossal 105 kicks from both sides, and a ratio of rucks to kicks of rather less than two to one (1.65 rucks to every kick, to be precise).

When teams kick the ball away to that extent, it means that they are using the kick not just to exit their own last thirds of the field, but as a specific weapon much further upfield. No less than 39 kicks in the EP final were made from the area in between the two 40 metre lines, which has been traditionally viewed as the best space from which to attack with ball in hand, with a range of options available and both passing and kicking games in play.

The kicking game employed in between the two 10m lines only really works if you have a specific target in mind. Leicester had clearly decided to target the Saracens scrum-half Aled Davies in their pre-match planning, as Davies is usually deployed on the right-hand side of the Saracens backfield. Tigers knew where to find Davies defensively, and they played their hand for all it was worth:

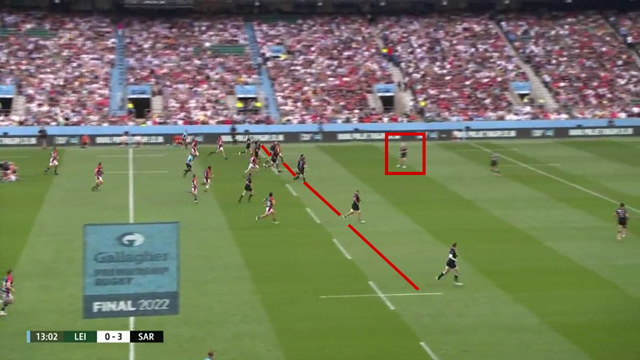

Ex-Saracens number 9 Richard Wigglesworth drops the box-kick from his own 40m line straight on to Davies and draws the fumble, and it is likely he was promoted to the starting XV for just this purpose. Aled Davies (in the red rectangle below) is unprotected and therefore he can be targeted:

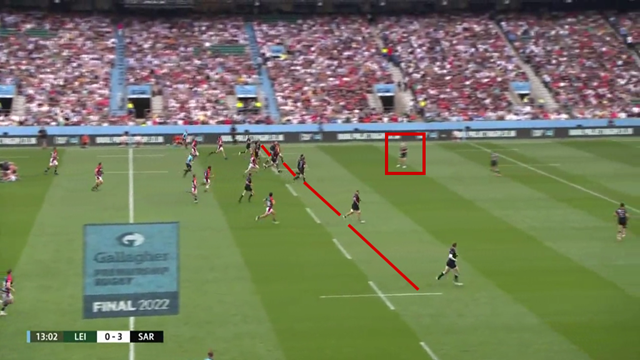

A few phases later in the same sequence, Leicester went back to the well for a second time:

On this occasion, the kick is made from just inside the Saracens own 40m line, and the question is put to Davies’ decision-making as he runs back towards his own goal-line. In the event, he gives his full-back Alex Goode a hospital pass and Goode is forced to concede a five-metre scrum by carrying the ball into the in-goal area.

The pressure from the Tigers’ midfield kicking game all came down the same side of the field:

It is an unequal contest between 6 foot 5 inches of England full-back Freddie Steward, and Davies tracking out of the right half of the Saracens backfield. Players who feel they are being placed under pressure consistently are more likely to make mental and physical errors. In the 26th minute of the first period, Davies committed a head-high tackle on hooker Julian Montoya, and that meant a 10-minute sojourn in the sin-bin on a yellow card:

Leicester scored two tries and 12 points in the period Aled Davies was off the field and took control of the game on the scoreboard.

In the second half, Saracens looked to insert their imposing number 8 Billy Vunipola into the space just ahead of Davies when they knew the kick was coming:

The plan worked well for a while, with big Billy taking the ball in front of Davies on four consecutive occasions in the third quarter when Leicester went to his side with a high bomb. The Tigers eventually found the right length of punt to cause confusion between the pair:

Aled makes another poor decision to move the ball on to his number 8, and that results in another scrum (and pressure position) to their opponents. Pressure exerted in the same zone by the kicking game has long-lasting consequences. With both Davies and Vunipola off the field as the game reached its final stages, the key defensive zone was left completely untenanted:

There is no Saracen within five metres of the ball when it lands, and Leicester were able to hold on to their position for long enough to set up a Championship-winning drop-goal attempt by Freddie Burns. That was game, set and match to the Tigers.

Summary

The lesson from recent rugby finals played all over the world at club and provincial level is that pressure pays, and pressure produces mistakes. Teams set up primarily to kick and defend, like Leicester and Saracens, will happily avoid all handling and ruck retention risks in between the two 40 metre lines and look for specific targets in the backfield with the kicking game. Then it is a case of ‘rinse and repeat’, and of attacking the same target until its discipline and concentration begins to break down under stress. It is not sexy rugby, and it is probably not what the law-makers were envisioning when they changed the breakdown rules, but it is mighty effective.

.jpg)

.jpg)