There are myriad approaches to playing the pivotal number 10 position in Rugby, and it can be hard to know how to achieve the required balance when there are more than one of them on the field. How do you blend the player with great instinctive skills, the one who can spot gaps and exploit them, with the more considered game-manager, the player who can take a step back and implement the right strategy to move his team up and down the field?

Very seldom do you get the Dan Carters of this world, those who can do both with equal facility. Usually there is a choice to be made. England are a fascinating test case. They have been struggling for the better part of two years now, to integrate the intuitive ball-skills of young Harlequins #10 Marcus Smith, in a team which has historically depended on two excellent game-managers (Owen Farrell and George Ford) for much of the past decade.

The previous coaching regime of Eddie Jones looked to solve the problem by picking Smith at #10 with Farrell at #12 outside him. In the event, it did not work. For his club, Smith is a brilliantly instinctive counter-attacker. The less time he has to think, the better he plays:

In these two clips from the same game against the Bristol Bears, Smith is under severe pressure when he receives the ball and improvises a kick ‘on the hoof’. The first creates a break out wide, the second chip is regathered by Smith himself for the score. Both plays are all about instant reaction, and problem-solving in unstructured situations.

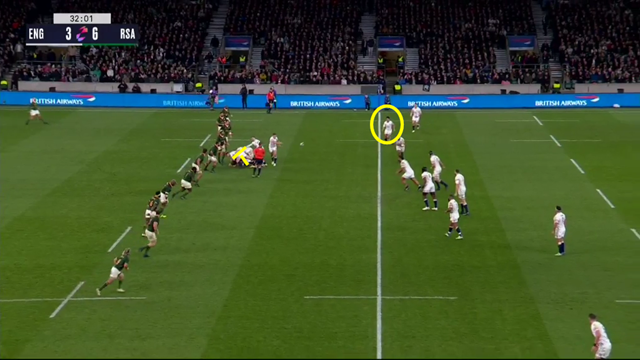

Now look what happened to the same player when he was asked to play the position for England. The following sequence, from the match against South Africa in late 2022 (Jones’ last in charge) was typical:

Smith passes to Farrell, and after the ball is taken into contact, the young pretender finds himself isolated on the short-side, well away from the next phase, while Farrell has committed to the cleanout:

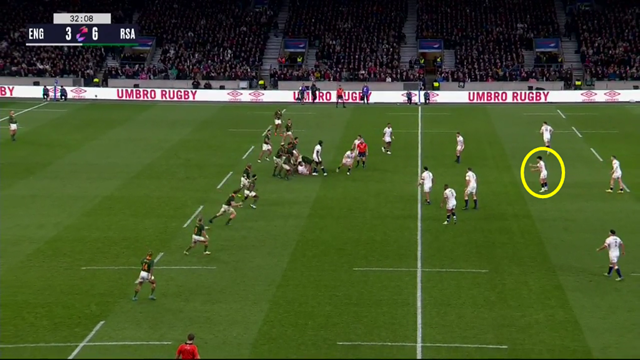

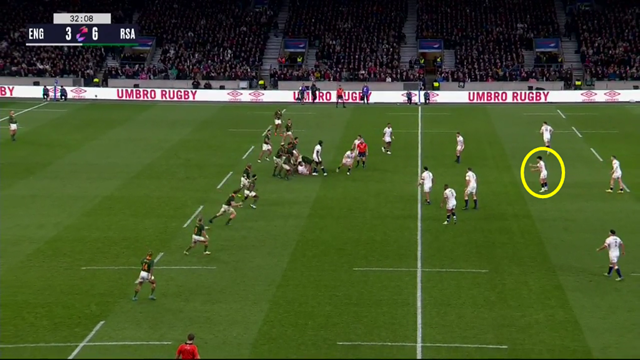

After one more phase producing very slow ball from the ruck, Smith is back in place at first receiver, but he has no other option but to kick the ball away. England’s attacking shape has been lost completely, and Smith is left standing behind most of his support.

The kick generated a counter-attack try for South Africa rather than England:

The sequence illustrates the difficulty Marcus Smith had in playing within a structure where the game-manager was playing outside, rather than inside him. After the ball is shifted right, he runs straight past the play to the short-side, Farrell attends the ruck and that leaves South Africa defending a ‘no threat’ phase consisting only of English forwards. The knock-on effect is a defensive kick on third phase, with the Springboks better set up on the return than England are on chase.

That was Eddie Jones’ last match in charge of England. The challenge for his successor Steve Borthwick has been how to find a role where Smith’s undoubted abilities can find the room to breathe, and thrive. Borthwick’s solution at the World Cup has been to move Marcus further away from the heavily-structured aspects of attack, and into space.

In the latest round of matches versus Chile, he picked Smith at full-back with Farrell at #10 to do the structural spadework closer to set-piece:

The structure inserts three England backs in between Farrell and Smith – both centres on decoy runs and blind-side wing Max Malins passing the ball to the Quins’ wizard. That gives him the ball in space, and then his instincts take over. The sidestep and the offload occur without thinking, and Marcus is suddenly living in the sweet spot of his rugby psyche again.

It is first phase turnover and the Chilean defence is out of shape, but the key is Farrell’s shift from one side of the ruck to the other to realize where the gap will occur. He inserts himself at first receiver in order to play provider to Smith, who is the better of the two at exploiting the space with his natural array of skills. Both are essential to the score, but this time they are working in the right order. Strategic view first, instinctive execution second.

Summary

A Dan Carter is rare jewel indeed. Most number 10’s are either strategist/game-managers or they are instinctive ball-players. It has taken England the better part of two years to fit Marcus Smith and Owen Farrell into the same team. Both Eddie Jones and Steve Borthwick began with Smith at #10 with Farrell at #12, but there is no point in sliding the game-manager outside the ball-player. Reverse the situation, and pick Farrell at #10 and Smith at #15, and the outcomes are immediately improved, at least on attack. It just requires a little ‘blue sky’ thinking.

.jpg)

.jpg)