The most basic version of attacking in the professional era is the so-called ‘same-way’ or ‘around the corner’ attack.

The idea is a simple one: to set rucks quickly and move your own attackers around the outside edge of the breakdown more quickly than the opponent is able to do on defence. The theory goes that, by the time you have reached the far side-line, you will have created an exploitable gap.

The staple for same-way attack is the delivery off number 9 rather than number 10. The forwards have to be able to roll into a realistic attacking space, one which they can reach in the five of six seconds it will take to set up, and win the preceding ruck.

Once you have the building blocks of a sound same-way attack in place, you can begin to build and elaborate.

For example, Wales of the Warren Gatland era would utilize the ‘exhaust and stretch’.

Wales used a succession of same-way forwards attacks off 9 all the way across the full width of the field, to exhaust the defence on the way out; at the same time, they would reassemble a full back-line with extended line spacings, to stretch it on the way back to the original side-line, in one single phase of offence.The recent Gallagher Premiership match between leading lights Saracens and Leicester Tigers contained some model examples of how to run, and how not to run a basic same-way attack from lineout.

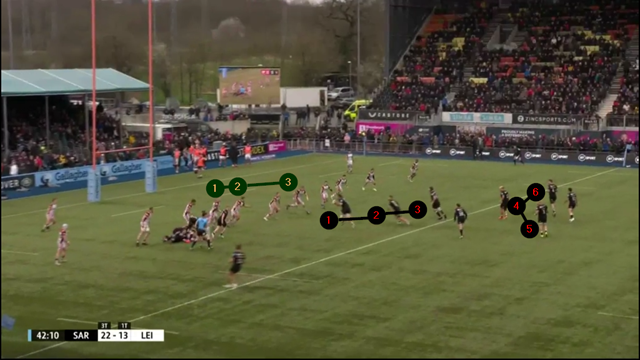

Firstly, let’s take a look at a successful example by Saracens. The start-point is full 7-man lineout on the Leicester 22 metre line, so both sets of forward begin on an equal footing, with the same distances to run offensively and defensively:

The lineout is scrappy, with Saracens’ hooker Tom Woolstencroft having to move across field to connect with the first ball-carrier, Wales centre Nick Tompkins. Crucially, Tompkins breaks the first tackle and makes another seven metres in contact. The first ruck then consumes two forward attackers (on cleanout duty) and two forward defenders (in the tackle), and that represents a situation of advantage for the attack as the shot widens:

Three Leicester forwards have made it around the open-side corner of the ruck, but all of the other six Saracens forwards are already ‘in pod’ and ready to play:

The second phase of attack between number 8 Billy Vunipola and number 6 Andy Christie (with support from second row Tim Swinson) takes out all of the Tigers’ forwards who made it around the corner of the first ruck, and extends the Saracens advantage to tipping point:

A basic head-count shows that there is only one Tigers forward left (number 4 Callum Green), desperately trying to make it around the ruck to defend a yawning space. But there are two Saracens tight forwards already primed to strike:

It is a hopeless defensive situation for the second row, and the Saracens receiver (Alex Goode) cleverly draws Green on to him before releasing one of the unmarked tight forwards (number 3 Vincent Koch) with an inside pass:

All in all, it is a very lucid sequence illustrating how positive collisions can exhaust the defence’s ability to keep pace around the corner of the ruck on a succession of same-way plays.

Now let’s look at a failed version of the same attacking pattern, again starting from lineout within the opposition red zone:

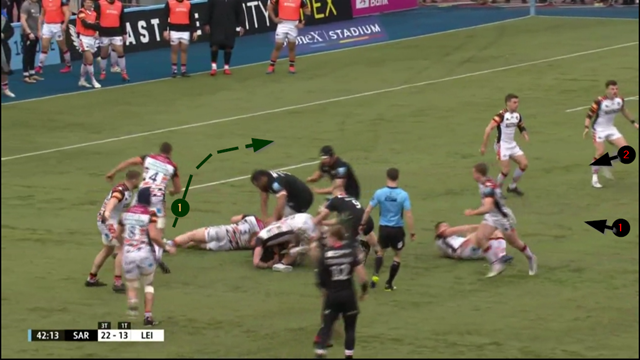

With the first tackle by Tompkins denying the ball-carrier (Leicester centre Matias Moroni) positive yardage and taking play further infield towards the posts, Saracens are winning the race around the corner of the first ruck:

https://ngm-blog-images.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/Sameway+4.png

Saracens’ hooker Woolstencroft is already attending the ruck, but the first Leicester forward (number 8 George Martin) is struggling to make up ground:

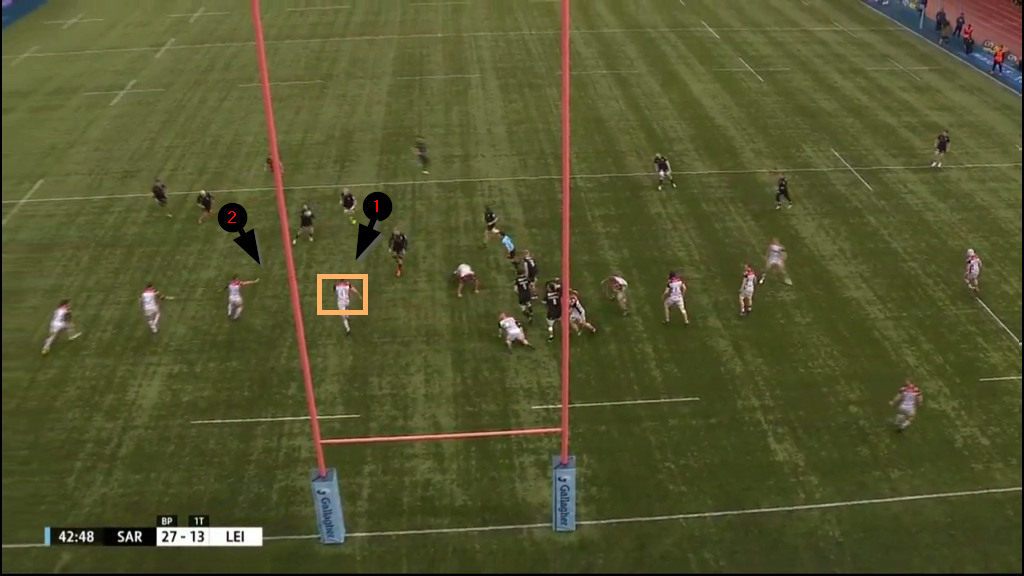

With no Leicester forwards beyond him, Tigers scrum-half Jack van Poortvliet is forced to take on the ball himself, and when the shot widens again it becomes clear that Saracens have won the race to the far side-line:

The width of defence extends about 10 metres beyond the attack, and both of the remaining two Leicester backs (Freddie Burns and Kini Murimurivalu) are already looking to come infield. The final phase confirms what we already know:

Murimurivalu has to take in the ball on a pick and go play and Burns is first held up, then knocked back in the tackle. In an attacking sequence principally designed to feature the forwards, backs have made four of the first five carries, and that is a sure sign of failure.

Summary

Most of the best sides in the world are able to implement an effective same-way attack, and very few can do without it entirely. Positive collisions, quick ball placements and work rate around the corner of the ruck by the forwards are essential building blocks in the success of a pattern which remains one of the fundamental platforms for success.

.jpg)

.jpg)