How to manipulate the short-side from lineout

The drive from lineout has become probably the most profitable means of attack from set-piece over the past few seasons. It has taken over from the scrum in that respect.

At the scrum, there is only one place to put the ball in and all of the forwards start in technically, their strongest positions. Offensive players may have to use their feet to direct the ball towards the base, which can cause instability. The number 8 must concentrate on controlling the ball with his feet, and cannot see the picture ahead of him like the ball-carrier in a maul. There are more things which can go wrong.

At the lineout, the attacking side can choose where they want to throw the ball, and they can look to deliver the ball into areas where their blocking wall will be stronger than the opposition defence. The ball in hand is easier to control than the ball at the feet, and players who start at the back of the drive can move past the ball to become blockers in front of it.

In short, the lineout drive is a better form of legalised obstruction than the scrum!

It can be a particularly effective ploy to preface an attack on the short side with a lineout drive, and this was a consistent theme in the recent Bledisloe Cup series between New Zealand and Australia.

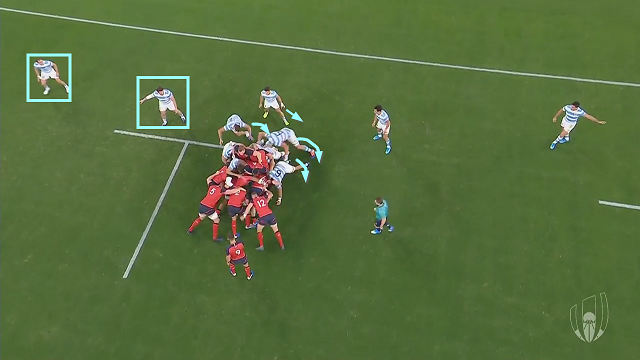

The first example however, comes from England’s 2019 World Cup game against Argentina, at a lineout deep within the Pumas’ 22m zone:

The initial receipt is made on the 15m line, then the drive rolls infield towards the Argentine posts. First one, then two England backs assist in the process of adding weight to the push over the right side of the maul. First #12 Owen Farrell, then #9 Ben Youngs initially bind on to the ball-carrier (#2 Jamie George), then move past him further up the maul to become blockers. This effect cannot be duplicated at a scrum.

The panoramic overhead shot from behind the posts reveals more about England’s real attacking intentions:

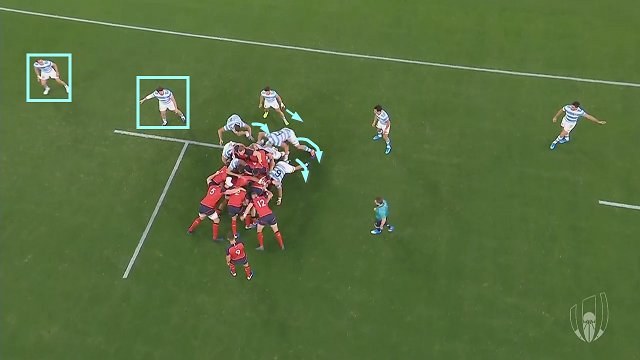

As the drive develops towards the posts, no less than seven potential Argentine defenders feed themselves successively into the maul. Only two defenders are left to man the short-side: one is a hooker (#2 Julian Montoya), and the other is the #10 Benjamin Urdapilleta:

On the attacking side, the England number 10 George Ford shifts late across to the narrow side to join left wing Johnny May. When the ball is released, it is an unequal contest: England’s best ball-handler and their best finisher, set against an Argentine forward and their smallest back, in more than 20 metres of space:

Examples from positions much further upfield were evident in the Bledisloe Cup series:

Timings are an important factor compared to the scrum. Most scrums seldom last more than 7 seconds before the referee calls for the ball to be used, or some form of illegality is detected and he awards a penalty.

The lineout drive can be sustained for far longer than that, because the rules governing it a far more liberal:

16.15 – When a maul has stopped moving towards a goal line, it may restart moving towards a goal line providing it does so within five seconds. If it stops a second time but the ball is being moved and the referee can see it, the referee instructs the team to use the ball. The team in possession must then use the ball in a reasonable time.

The attacking side can temporarily stop, regroup and then begin again within five seconds. As long as they can achieve slight forward progress, they can keep probing for weaknesses in the defence.

In the above example, the original lineout receipt was made at 32:33 on the game clock:

The break down the side-line occurs 27 seconds later – and that would not be possible from a scrum!

The extra time afforded to the attack can be used to shift personnel around to its advantage. England moved their #10 to join their left wing in a mismatched short-side attack. The All Blacks have their dynamic number 8 Ardie Savea widen towards touch at 32:50, and he finds himself opposite the Wallaby half-back Nic White. It is numbers 9+8 versus numbers 2+9, and that is a situation the All Blacks can exploit.

The lineout drive is a more robust, manageable platform for set-piece attack than the scrum, especially if the short-side is the target area. The attacking side can keep the ball for longer, probe for weaknesses and create more potential mismatches on that narrow side of the field. The target area may be short, but attacking possibilities are long on potential!

.jpg)

.jpg)