How to take the short-cut to success off first receiver

The concept of two lines of attack has been around for most of the professional era. It first came to prominence on the British & Irish Lions tour of Australia in 2001, when the Lions head coach Sir Graham Henry formulated the idea of using forwards as a front line to engage the defence, with the backs as a wider option behind them.

Since then, many refinements have been added to the mix, even if the basic idea remains much the same – the number of forwards in the front line (one, two or three?), the identity of the distributor lurking behind them (#10, #12 or #15?), and the distance between the two elements of the attack.

The occasions on which the two lines of attack are used with impact, and with the right balance of elements, are still relatively few in number. For the concept to work at full power, both threats have to be convincing: the flat or short ball to the ‘forward’, and the ball out of the back door to another back-line distributor.

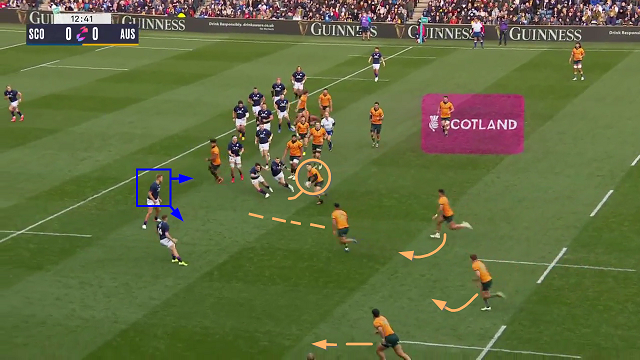

Too often in practice, the short ball is ignored in favour of the pass behind the man, and straight into the second line of attack. Here is a recent example of that common mistake from the end of year tour game between Australia and Scotland. The Wallabies are on attack and have the two lines in place:

Australia would like to use the full width of the field and exploit a situation in which they have a potential two man overlap on the left-hand side. In order to achieve that aim, they have the engage the key defender, Scotland’s outside centre Chris Harris (in the blue rectangle):

Harris is standing on balance, and is able to move either way – he can link with the inside defenders, or shift to the outside to join up with Scotland number 14 Darcy Graham. The purpose of the short ball is to move him off that point of balance and away from the target area.

In the event, the first line run by Australia’s Len Ikitau fails to convince Harris to take a step inside, so the second line of attack finds itself opposed by an organized line of defence a few metres further downfield.

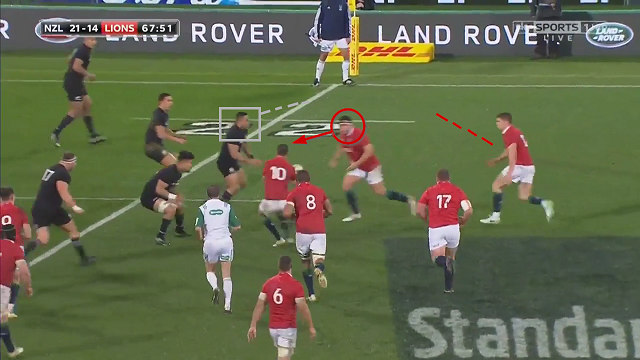

Now let’s take a look at a couple of instances where the short ball becomes a shortcut to the try-line. Wind the clock all the way back to the second Test between the Lions and New Zealand in 2017:

There are some subtle differences in this example, compared to the instance from the Scotland-Australia game. Here the first receiver (Ireland’s number 10 Johnny Sexton) keeps the short ball option alive a little longer before committing to the pass, and that forces the defender to declare his hand:

The key New Zealand defender (centre Ngani Laumape) has been drawn off-balance on to the Lions’ back-door option, number 12 Owen Farrell. That opens the path for England hooker Jamie George on the short ball, and the Lions convert the break into a try on the following phase.

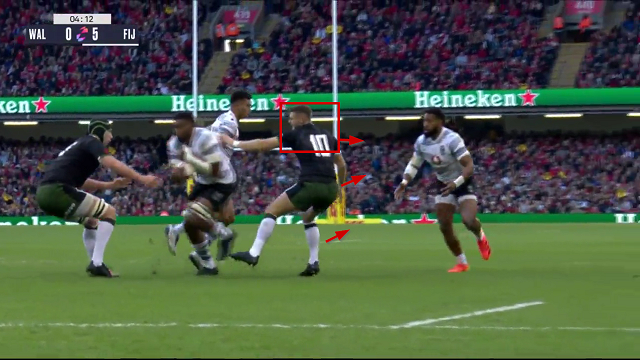

Now for a more recent example from the weekend game between Fiji and Wales at the Principality stadium:

There is a forward in the first line option (Fiji number 8 Viliame Mata) with outside centre Waisea Nayacalevu as the second line alternative. Once again, the aim of the play is to drag the key defender – Wales number 10 Dan Biggar – off his centre of gravity and away from the intended zone of attack.

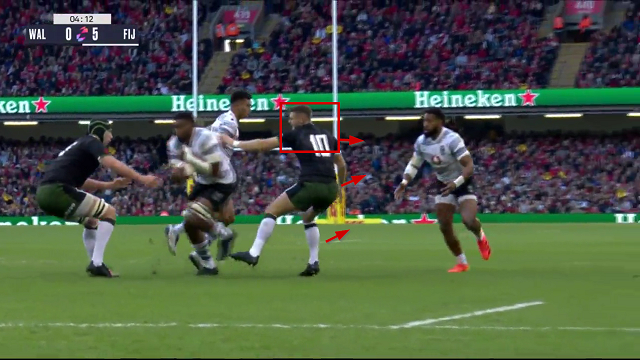

The screenshot from behind the posts makes it crystal clear that this is exactly what happens in the course of the play:

Biggar shifts his weight to the outside anticipating the threat of Nayacalevu, and can only throw out a despairing arm when Mata receives the short, angled ball. There is no possibility of a realistic tackle completion at all.

Here is the full sequence, in slow motion, from behind the posts:

Modern professional defences are coached to keep their width, and defenders will often subconsciously write off a forward runner in the first line as a decoy, in order to move out on to the (perceived) greater threat from a second line back out wide. As a consequence, the first line option to the forward is often under-used, when in fact it can provide a relatively simple shortcut to the try-line.

.jpg)

.jpg)