How to use ‘joined-up thinking’ in your game-plan

How do you find a clear plan of action on a rugby field? There are so many factors to consider, and your own preferred style of play is only the start.

You have to weigh your own strengths and weaknesses relative to those of the opposition – how do you match up? Are those characteristics similar or contrasting? How far should extend the plan outside of your ‘normal’ range?

Then you might want to feed in other factors, such as the ground and weather conditions, and even the type of refereeing that can be expected.

Especially with the benefits of modern technology, there are many alluring statistics available upon which the game-plan can be based. The sheer information overload can muddy the waters and the make the process of forming a plan much more difficult, rather than easier!

One of those double-edged swords is the division of the playing field into ‘grids’ or different areas of action, both horizontally and vertically. Horizontally, the pitch can for example be divided up into three sections: the two zones marked by the 15 metre lines outwards to touch, and the midfield area in between them.

Vertically, the pitch can be split into three or four zones depending on whether you are in ‘exit’ mode from your own end (typically 1-35m from your goal-line), in the opposition red zone (75-100m) or somewhere in between (36-74m).

The plan, and the proportion of kicking and running contained within it, will vary according which ‘grid’ you are in and to where you are on the field. Typically, you may play more conservatively at both ends of the pitch (vertically), and possibly also in the wide zones (horizontally).

In the final analysis, it doesn’t matter what you do – as long as your thinking is joined-up. The plan has to enjoy a clear sense of connection from one zone to the next, so that the player’s actions can be triggered immediately, as if by instinct. If they have to hesitate and think about what to do next, the plan is not working!

The most important factor in the coaching guidebook is clarity, even if that means certain limitations. Better to know one play from top to bottom and in all of its variations, than to know three or four options by halves, or incompletely.

The great coach of the 1960’s Green Bay Packers, Vince Lombardi, used to teach a play called the ‘power sweep’:

“You think there’s anything special about this sweep? Well, there isn’t. It’s as basic a play as there can be in football. We simply do it over and over and over. There can never be enough emphasis on repetition. It’s my number one play because it requires all eleven men to play as one to make it succeed, and that’s what ‘team’ means…Every team eventually arrives at a lead play. It becomes the team’s bread-and-butter play, the play that the team knows it must make go, and the one the opponents know they must stop. From continued success with that play, your confidence can grow."

You find the plays which make most, or all of your players work for a positive outcome, and you ensure that those (few) areas you identify are really points of leverage where you can hurt the opposition.

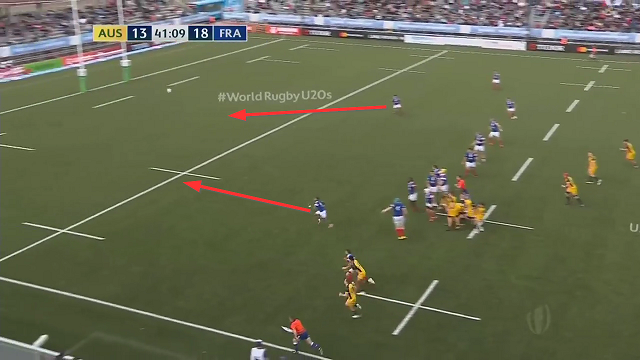

Let’s look at an example where clarity of thinking in the planning stage translates on to the pitch as play moves across different zones. This sequence comes from the recent France-Australia under 20’s World Championship final.

Australia has the ball on the outer edge of its own exit zone (40m), and has to decide how to advance the ball as play moves into the middle third of the field

The junior Wallabies elect to kick high off their number 9, Michael McDonald, in order to create an aerial contest and reclaim the ball. Why? Firstly, because McDonald is accurate with the boot: the ball travels the right distance (22 metres), with enough hang-time (about three and half seconds) for the principal chaser to contest the ball as it comes down.

The second reason is that the chaser (number 11 Mark Nawaqanitawase) is 6’3 inches tall, and with soft hands. This means that if the kick is right, the chase will be productive rather than futile.

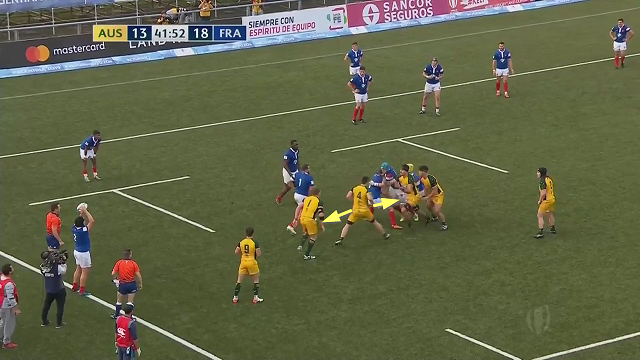

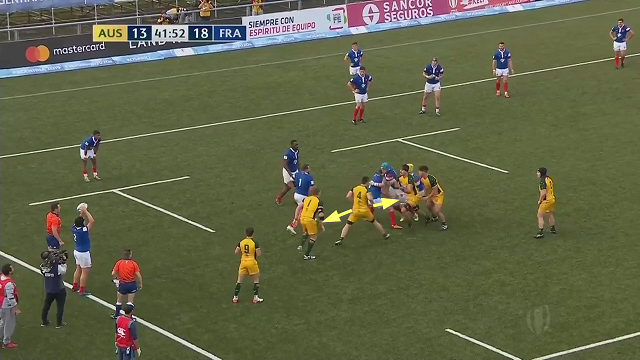

The junior Wallabies also get other little details of the play just right:

There are four Wallabies around the ball, one more than their French opponents, while two other forwards are primed to join the contact situation from excellent angles of entry.

Now that they are in the middle third of the pitch, what to do next? McDonald has no hesitation, because he knows what to expect in a situation when the ball has been reclaimed from a high kick

The French defender contesting the high ball with the Wallaby left wing was the full-back, which means that the last backfield player has been consumed and the area behind the line is temporarily empty:

We already know that McDonald is an accurate kicker off his right foot, and now he demonstrates that same precision off his left. The new point-of-leverage has been correctly identified, and the ball takes one hop before rolling into touch only seven metres from the French goal-line.

So how can we join up the thinking about the strength of our kicking game with the new field position in the opponent’s red zone? The answer is by using the strength of the Wallaby defensive lineout

The key players as the four-man line sets up are the two Wallaby forwards in the middle – number 4 Michael Wood at the front, and number 5 Trevor Hosea behind him.

How do we know that the Wallaby lineout is a strength? Because Wood and Hosea are not beaten by the first French (decoy) move before the throw. Hosea marks out the move towards the tail, but the Australians remain flexible and do not commit to him as the receiver:

Wood at the front is still braced to go either way, and become the jumper as easily as he can provide the front boost for Hosea. This is a priceless advantage over a short lineout which can only feature one set ‘pod’/receiver against the throw.

So, when French movement comes back towards the front, Wood is prepared to contest the throw, with Hosea lifting behind him. And what do the Wallabies do with the ball next? – they give it immediately to their strongest ball-carrier (number 8 Will Harris) to move play all the way up to the France goal-line itself, with a try imminent.

The sequence as a whole is an excellent example of joined-up thinking, about how to connect your points of strength together up and down the field, while involving as many different players as possible to create the sense of team-ship Vince Lombardi mentions. Australia highlights its best kicker, its best chaser and ball-carrier, and the strength of its defensive lineout as play successively crosses the invisible demarcation lines between zones. If he knew the game of Rugby, one can only imagine Lombardi himself nodding in appreciation at the clarity of thought and execution involved.

.jpg)

.jpg)