How to use late movement on attack close to the ruck

The ruck in Rugby can be both a curse and a blessing. If you get consistently slow ball delivered from it on attack, it gives defences invaluable breathing space to regroup and set up properly for the following phase. If you can get quick ball from two or three rucks in a row, chances are you will be able to find a hole somewhere.

While a great deal of time is spent, and rightly so, on improving the speed of ball delivery from a ruck, it is just as important to focus on the movement around it. Most rucks create their own geography, and two sides for the attack to explore.

If you can move your players from one side of the breakdown to the other more quickly than the defending side, it is another string to your bow, and an extra way of creating an advantage.

If it is to be most effective, this movement has to be as late as possible in order to minimize the reaction time for the defensive team. It does not need to involve either a lot of players, or a lot of passes in order for the ‘late overload’ to be productive and create a break in the line. It is a low-risk, but high effort play.

Let’s take a look at two examples from the current Super Rugby Trans-Tasman competition. Neither are complicated: both plays are run off short passes from the number 9 and depend on a late movement from one side of the ruck to the other by just one forward – the attacking number 8 in both instances.

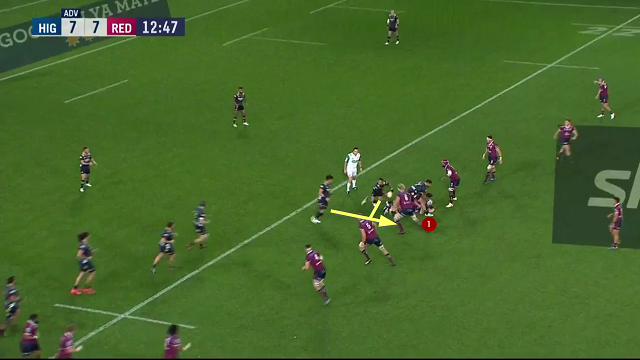

The first example comes from the round one game between the Highlanders and the Reds at the Forsyth Barr stadium in Dunedin:

The Highlanders set a ruck in midfield near their own 22, and the success of the following play derives from two elements: the late movement of their number 8 (Kazuki Himeno) from one side of the ruck to the other, and some subtle nuances on the pass to launch him through the gap by number 9 Aaron Smith.

Ad the ruck forms, Smith suggests by the position of his head and feet that he is setting up to pass out to his left:

The three Reds’ defenders on that side immediately shuffle out when they read the cue. In fact, Smith is prompting Himeno to switch sides and pop out to his right. The Reds defence is static, but the Highlanders’ attack is still dynamic and in motion. The outcome is a simple overload on the defender (Angus Scott-Young) on the right:

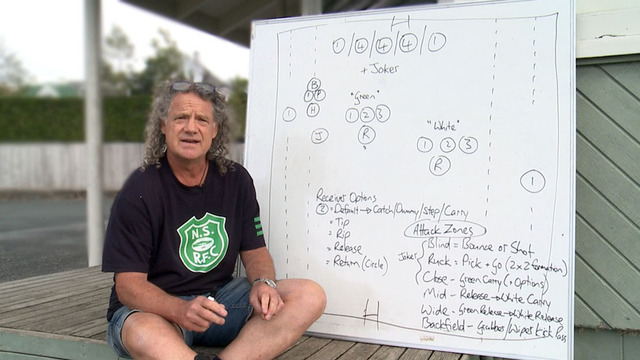

Once the principle is established, it is possible to build a more elaborate pattern around it:

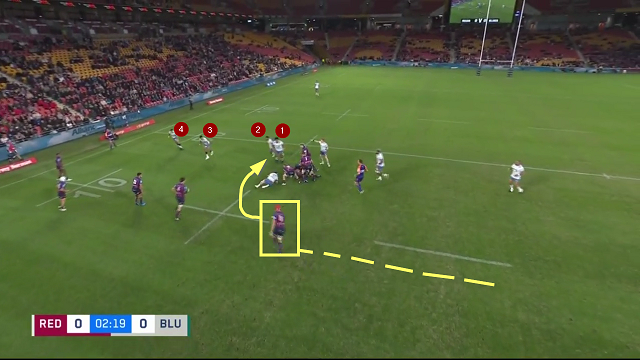

This example comes from early in the recent Trans-Tasman match between the Reds and the Blues. The key runner (Queensland number 8 Harry Wilson, in the red hat) will shift across the whole width of the field over a couple of phases to provide the extra man in attack.

Wilson starts attending a ruck near the right-hand 15 metre line:

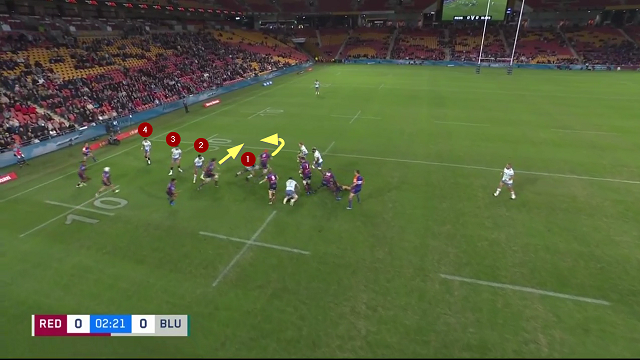

Then he tracks all the way across to the left by the time the second ruck is complete:

Prior to Wilson’s movement, the Blues short-side defence is fully numbered up on the Reds’ attackers opposite, four on four. By the time Wilson reaches the critical space outside Queensland scrum-half Tate McDermott, the short-side D is fixed and the Reds have manufactured the overload on the ‘Guard’ position closest to the ruck:

The Reds are dynamic and in motion, while the Blues are static. That gives the attacking side access to the support lanes after the initial breach is made – so there is very chance of the attack maintaining its momentum.

Successful attacks do not require complex schemes, or a huge number of moving parts. It can be enough to be able to move one player from one side of the ruck to the other quicker than your opponent, and time his insertion into a sensitive spot at just the right moment – all with some subtle help from your half-back!

.jpg)

.jpg)