The last image of a memorable Women’s World Cup final between the Black Ferns and the Red Roses was a lineout steal on the goal-line by New Zealand. If it hadn’t been made, it was all but certain that England would have scored from another drive to seal the fate of the game in their favour:

The Roses had already scored four tries from their maul in the match, some starting from as far away as 15 metres from the goal-line, and they would have done so again if Abby Ward had returned to terra firma with the ball safely tucked away. As it was, the Ferns’ replacement lock Joanah Ngan-Woo took the brave decision to counter-jump and turn over the throw at source.

It is risky, because three defenders (one receiver and two boosters) are automatically being subtracted from the defence on the deck. Moreover, it is not a repeatable tactic, because a well-drilled attacking lineout will expect to win nine out of every ten throws it delivers. Instead, the defence will need to select at least one specialist in lineout drive disruption, a dominant maul defender, and he/she usually comes from the second row.

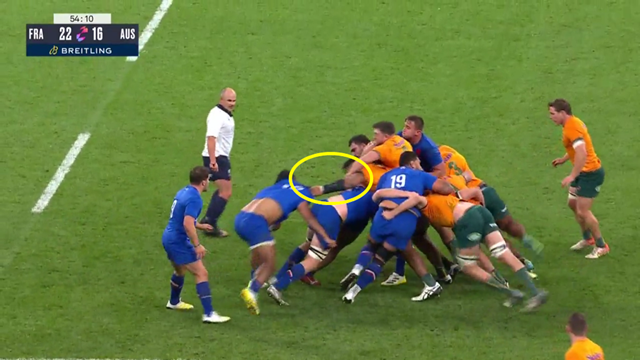

One such maul defender is the Wallabies’ Will Skelton. Skelton is a giant – 6 feet 8 inches tall and tipping the scales at around 140 kilos – and he knows how to use his physical tools to impose himself in close-contact situations. This driving lineout occurred in the recent game between France and Australia:

The French drive is moving sideways and Skelton has broken the bind at its tip, next to the receiver. Once he gets one long, powerful paw on the maul ‘rudder’ at the back, it is over for the attack and they are forced to release the ball under circumstances favourable to the defence.

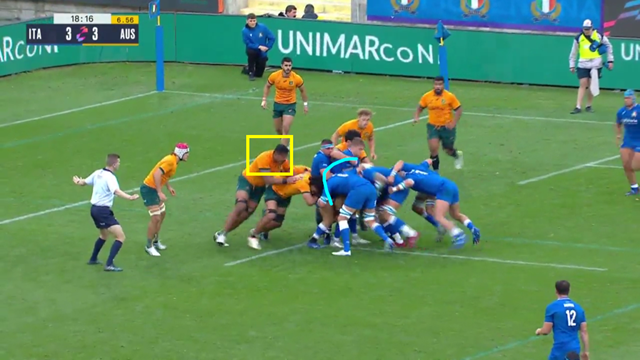

It was very much the same story when Italy tried the drive against the Wallabies in Florence one week later:

Skelton is positioned directly opposite the receiver (in the headband) and immediately attacks the seam between the catcher and the blocker on his outside (Italy number 5). He drives his upper body through the gap like a wedge and locks that prehensile left arm on to first the second, then the third layer of the maul. The outcome is a sack, and a turnover scrum to the Wallabies.

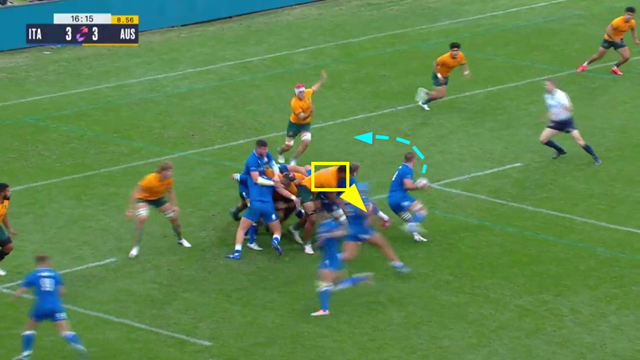

What do you do on attack, when faced by such a dominant maul defender? The Azzurri quickly realized that there was little further point in taking on Skelton directly, at the first point of contact:

The first counter-measure is throw away from the dominant maul defender. Skelton is in the middle of the line while delivery goes to the back, and this means that the big Aussie cannot interfere with the formation of the blocking front around the receiver. Instead, he has to skirt around the right edge of the maul and become a fringe, rather than a central figure as events develop.

The result is self-evident. With Skelton on the periphery, the drive advances all the way to the Australian goal-line, and a try is scored on the following phase:

The only time the Wallaby giant comes into contact with the ball is when the maul becomes a ruck, and he has to release the ball and roll away on the ground.

The second major tactic is to invite penetration on to the ball and move the ball away quickly from the point-of-contact around the edges of the maul:

The throw goes to the middle and Skelton bursts straight through the blocking wall, but the Italian forwards are prepared for it. The ‘rudder’ (number 8 Lorenzo Cannone) immediately breaks off around a soft open-side edge to make ground all the way up to the Wallaby goal-line. When the counter-push goes forward around a dominant maul defender, it often draws in the ‘Guards’ at the side of the maul in its wake:

On this occasion the quick shift away from the counter-drive moves around the short-side, with the Italy numbers 2, 7 and 11 establishing a numerical advantage in the 5m corridor.

Summary

The lineout drive was a primary feature of the Women’s World Cup final between New Zealand and England. The Red Roses scored four tries from it, while the Black Ferns replied with two 5m scoring drives of their own. The ability to establish a dominant maul defender is key for the defence, and it is equally vital for the attacking side to formulate alternate strategies to overcome that dominance once it has been proven. Italy’s ability to move the point of attack away from Will Skelton was a major plank in their historic victory in Florence, and it sets out an important template for the future.

.jpg)

.jpg)