Inside England’s red zone kicking game from Twickenham

England have reaped the benefits of probably the best attacking kicking game in the world since Eddie Jones took over as head coach back in early 2016. Arguably, they lost the World Cup final by moving too far away from that point of strength.

The habitually select two players with great experience at outside-half in George Ford and Owen Farrell (with Farrell moving to 12), they have Ben Youngs at scrum-half and the left boot of Elliott Daly at full-back. They can therefore, punish the opposition with a four-pronged kicking game coming off either foot.

Part of the attacking plan includes a constant refinement of the kicking game inside the opposition red zone, which extends approximately from the goal-line out to a position just outside the 22.

Why kick the ball away when you are so close to the goal-line? Would it not be better to keep the ball in hand? It sounds counter-intuitive. When you peel back the layers of the onion however, you discover a paradox at the core: it becomes easier to use the kicking game the closer to the scoring zone you get.

As the field begins to condense and the defending side has less space to mark in its own backfield, more players are freed up to play on the front line. This can create opportunities for the attacking team if they are prepared to ‘see the space opening in front of them’.

England introduced some important refinements in their red zone kicking game in the recent Six Nations game against Ireland, which probably derive from a familiarity with Rugby League. They used that to keep constant positional pressure on Ireland and create two tries from kicks directly.

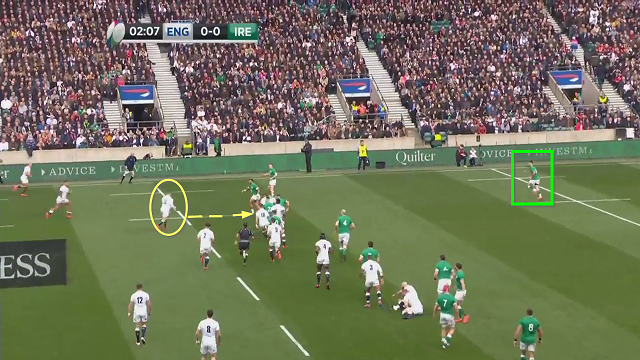

The first instance came as early as the third minute of the game.

England benefit firstly from George Ford’s instinct to square his shoulders and take the ball right up to the defence from 1st receiver. This encourages the defenders to believe in the pass play – not just the line defenders but the nearest backfield defender behind them, number 9 Conor Murray.

The time it takes Ford to move five strides upfield are enough to persuade Murray to move across the right 15 metre line and into the wide channel:

When he receives the ball at 2nd receiver, Elliott Daly has no real intention of passing. It becomes clear that England want Murray as close to the touch-line as possible so that they can deliver a kick inside him. Daly’s left-foot grubber travels directly along the 15m line, and parallel to touch. England establish a strong pressure position after Murray mops up the mess near the Ireland goal-line.

The inside kicking game was a feature of the first half, and it marks a departure of the typical practice where attacking teams tend to look for space behind the wings with diagonals or cross-kicks in the red zone.

England scored a try on the next occasion where they established a position near the Ireland 22. Here is the scoring phase from overhead:

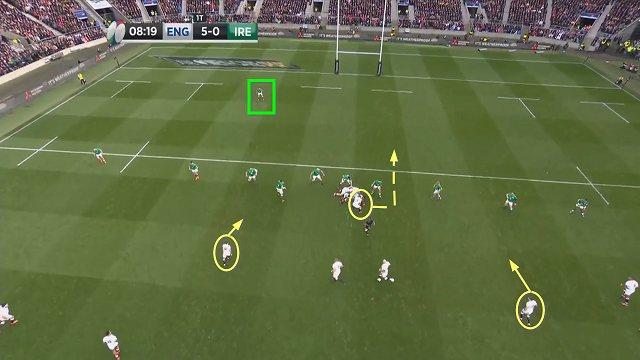

Before the ball emerges from the ruck, Ireland have good width on line defence – they have at least one player in both 15-5m zones. But the men in green only have one backfield defender, full-back Jordan Larmour:

The problem for Larmour is that England have two potential first receivers, standing on either side of the ruck – Ford to the left and Farrell to the right – and the full-back can only ‘sit’ on one of them.

As soon as he sees Larmour shadowing Ford, England number 9 Ben Youngs pulls away to the other side of the breakdown and delivers a kick along the same lines as Elliott Daly’s earlier effort. He doesn’t kick for the corner, but parallel to touch just to the right of the posts.

Although Johnny Sexton drops out of the line to safeguard the threat, he is beaten by the bounce of the ball and Ford touches down for the try. The two main pass receivers (Ford and Farrell) have become the primary kick chasers on the play.

That was not the end of the matter:

When George Ford receives the ball from the ruck, he does not consider cross-kicking to Johnny May on the right wing, even though May is probably England’s premier chaser of a high ball. The kick is directed inside, parallel to the side-line and just to the right of the posts. In this instance the ball again evades the defender and Daly touches it down for the score.

The common theme is that Ireland’s evident desire to defend the full width of the field in their own red zone has been used against them. Larmour is on the wide outside guarding May, and England are once more utilizing players who would usually be considered play-making receivers (Daly and Farrell) as the main kick chasers.

There is a lot of good thinking behind the plan: the most dangerous attacking play-makers are typically those targeted for the greatest defensive pressure, so it makes sense to put the ball in behind the players marking them. The receivers can then become the aggressors again, just this time on the kick-chase.

.jpg)

.jpg)