Is it better to play Rugby without the ball?

Over the past few weeks, we have taken a look at how refereeing culture can help promote a constructive vision of the game. This has happened in the English Premiership, where the emphasis on generating very quick ball from the rucks (for both attack and defence) produced a series of high-quality, ball-in-hand extravaganzas in the playoff stage of the competition:

Why the english premiership is ahead of the game

and

Why have the top teams stopped kicking for goal

With domestic tournaments across the world coming to an end, and Rugby moving into the international summer tour season, would the changes translate to Test rugby?

Based on the two highest-profile tours of the South by Northern Hemisphere sides – France to Australia and the British & Irish Lions to South Africa – the answer thus far, from three of the four teams involved (France, the Lions and South Africa) is a resounding ‘No’. All three much prefer to play the game without the ball.

In Australia, over the first two Tests France have made 44 kicks to Australia’s 27, completed 141 passes to 365 by the Wallabies, and built 123 rucks to Australia’s 238. Despite the huge disparity in territory and possession, both sides have scored exactly the same number of points (49), and France could easily have won both of the games.

In South Africa, the Springboks brains trust of Rassie Erasmus and Jacques Nienaber effectively promoted the recent midweek match between the Lions and South Africa ‘A’ to the status of a fourth ‘unofficial’ Test match when they selected 13 capped players in their starting XV at Cape Town.

It was a game in which both sides preferred to play most of the game without the ball. There were a massive 71 in-play kicks during the match, at a combined kick-to-ruck ratio of one kick to every 2.3 rucks. Compare that to Australia’s ratio of one kick launched, for 13.5 rucks built in the current series with France.

Some of the detailed stats are even more of an eye-opener. Of the 71 kicks made by both sides, 29 came from positions outside the 40-metre line of the kicking team, and 11 kicks were made in the opponent’s half of the field.

Within those stats, there were some interesting variations of the upfield kicking game, and some clear differences in philosophy between the home side and the tourists.

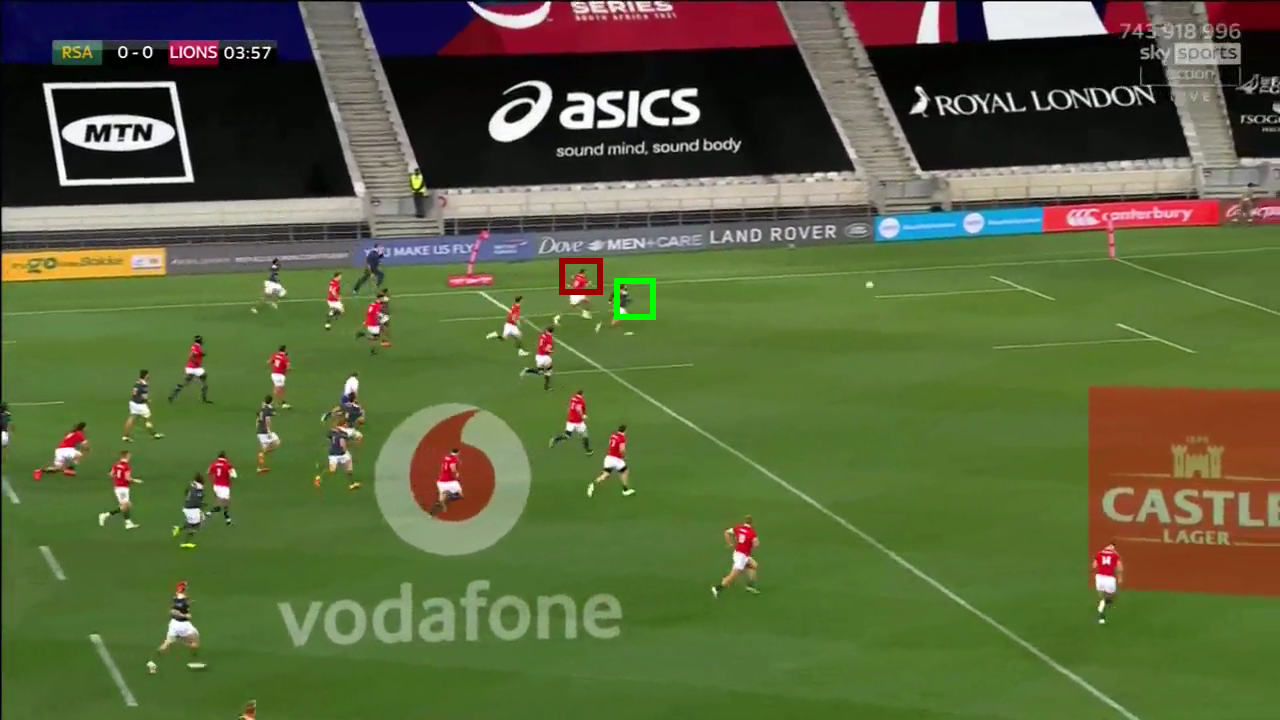

South Africa ‘A’ prefer to kick off their number 9, ‘Faf’ de Klerk from positions outside their own last third of the field. The kicks are launched from midfield out to the corners. Here is an early example in only the 4th minute of the game:

The Junior Boks have just won turnover ball from a fragmenting Lions breakdown, but there is no thought in De Klerk’s mind about shifting the point of attack with ball in hand. His only idea is to create a 50/50 foot-race to the corner between the two number 15’s, Willie Le Roux and Anthony Watson:

Likewise, it is clear from Le Roux’s attitude that he is always set up to chase the kick, not move the ball through the hands.

The kicks off De Klerk’s left boot were launched from position as far upfield as the opposing 22:

There is hardly any sense that the odds are even in the attacker’s favour as the kick is made. It is a 50/50 speculator simply designed to put the Lions’ backfield under pressure. The final example almost created a line-break for replacement wing Herschel Jantjies:

Again, the idea is to stretch the Lions’ backfield cover to the corner of the field, with Elliot Daly making a good tackle on Jantjies to snuff out the opportunity:

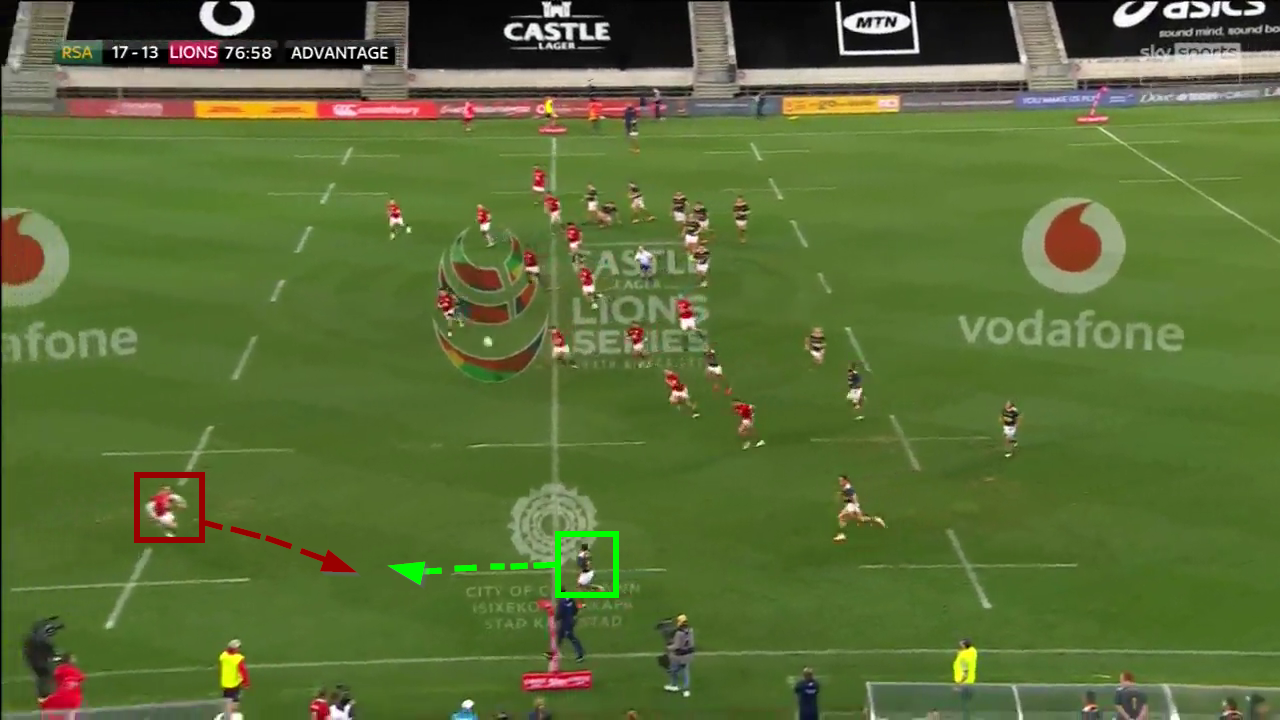

The Lions tended to look at the kicking game the other way around – launching kicks to regather, or recreate an unstructured attack on better terms:

There is evident pressure on the Junior Boks’ backfield as Le Roux goes back to field the ball, but the intention is different: once Le Roux inevitably gives the ball back via a quick lineout, the Lions want to move wide with ball in hand:

Why? Because there is an inviting mismatch on the left between a dynamic ball-running number 8 (Taulupe Faletau) and a South African second row (Franco Mostert).

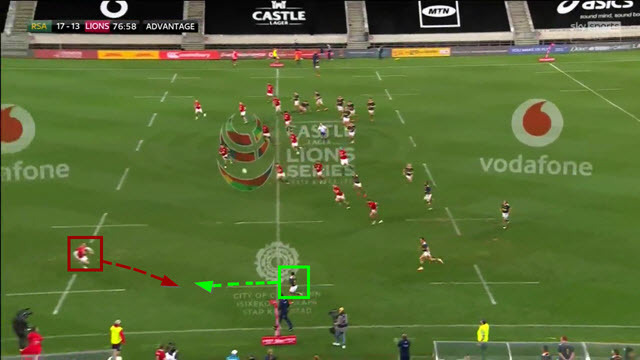

The same theme was repeated in a slightly different form in the second period:

After scrum-half Conor Murray successfully regathers his own high kick, the Lion’s one presiding thought is to shift the ball wide to the opposite side of the field. Faletau is again the key attacker out on the left, defended by the same Springbok forward, Franco Mostert.

Summary

The early evidence is that Test rugby is proving to be stubbornly resistant to the 2020 law changes, which were designed to promote quicker ruck delivery and more ball-in-hand attack. The French are kicking and defending in Australia, South Africa and the Lions are content to kick and defend, and wait for an error in the Republic. Rugby remains still a game played (if not enjoyed) best without the ball.

.jpg)

.jpg)