Is there a Renaissance in French rugby

Who will ever forget the try from the end of the world that France scored to overhaul the All Blacks in the final moments of the second Test on their 1994 tour of New Zealand?

That remains France’s only series win on Kiwi soil in the history of matches between the two nations. The end-over-end touch passing – not a spin pass in sight – the constant changes of angle to keep the attack moving straight down the centre of the field; and the deep, instinctive lines of support are still something to behold, after all these years.

It is a long time since a French side has been able to replicate that kind of attacking prowess in the professional era. Recently, there have been more green shoots of growth. The France national team has come within a whisker of winning both of the last two Six Nations tournaments, and the 2021 European Champions Cup final will be contested by two French clubs – Toulouse and La Rochelle.

Looking towards the World Cup in France in 2023, there has been more unity of purpose between club and country. A quota on foreign imports means that academies full of indigenous talent have begun to thrive, with a strong emphasis on diversity.

Led by the Parisian titans (Racing and Stade Francais), there is now much greater reflection of the ethnic mix within the country as a whole on the rugby field. French rugby is expanding from its heartlands into new regions like Normandy, aided by a competitive promotion-relegation structure which means that all of the D2 clubs vote in a democracy with their Top 14 brethren to decide the future of the game.

As a result, rugby’s TV contract in France is worth three times the amount generated by the English Premiership, and includes full coverage of every game in the second professional tier. There is a real sense that at last, the game in France is going somewhere.

On the field, some of those uniquely French characteristics are beginning to work their way back into the mindset of both club and country. Here is a beautifully-constructed try scored by Racing 92 in the group stages of the 2021 Champion’s Cup. Not quite from the end of the globe, but world-class in quality:

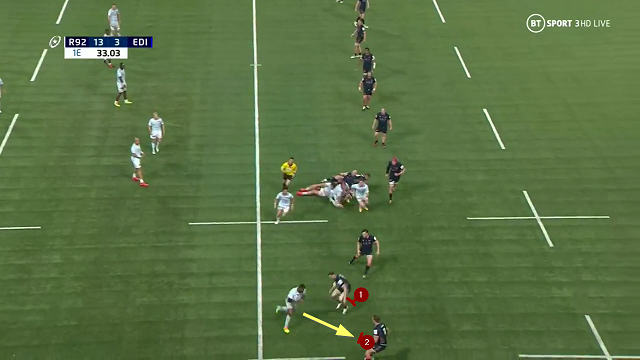

The French ability to manipulate a short-side to their advantage has always been one of their historical strengths. In this example, Racing 92’s opponents (Edinburgh) are fully numbered up in that area, so it requires some finesse to create space.

The primary task of the first receiver (number 13 Virimi Vakatawa) is to attract the attention of the last two defenders on the edge. Long gone are the days when the wing would stay out with his opposite number and leave Vakatawa to the inside cover. Now he is required to stay square, face front and hit.

That in turn defines the action of the attacker. Instead of the old doctrine of running parallel to touch and looking to draw-and-pass, he runs straight towards the final defender on an angle and looks to offload in contact. Vakatawa’s quick first step takes him away from the defender directly opposite and engages the wing:

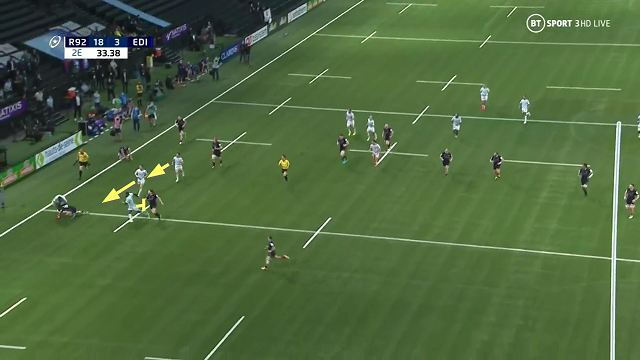

An offload out of the back of the right hand releases number 8 Jordan Joseph down the right side-line.

The course of Joseph’s carry illustrates a quality of support play of which The Rugby Site’s own Wayne Smith would heartily approve. The view from behind the posts provides the most revealing angle:

There are two basic aims with support play after a break:

(1) to ensure that the support players are closer to the ball than the cover defenders, and never blocked out of the passing lanes, and

(2) to maintain support in behind the ball-carrier until the very moment he/she is ready to pass.

In most situations, this keeps the option of a pass either way open, with a very low risk factor because the pass is so short.

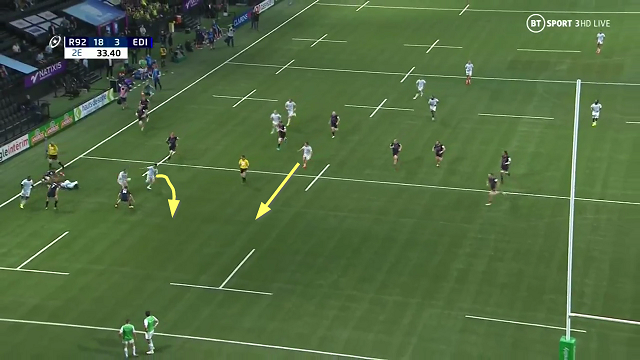

Racing 92 satisfy both of these requirements very accurately:

Vakatawa keeps running after engineering the break, and makes sure that he keeps inside position: he stays in between the ball-carrier and the closest Edinburgh defender all the way.

The first two support players are in a line directly behind Joseph – not spread across the field laterally.

Both Juan Imhoff and Maxime Machenaud only pop out of that ‘boot space’ when they know that Joseph is ready to release the ball. The passes are easy give-and-takes. Even if Machenaud does not score himself, the next player closest to the ball is also wearing blue and white hoops.

There have been other tantalising hints at national level, like this superb lineout try scored by France against England in the 2021 version of ‘Le Crunch’:

Again, not quite from the end of the world, but nonetheless beautifully conceived and executed in the traditional French manner. The subtle angles of running give the last attacker a free run in to the corner flag, a true collector’s item from first phase in the modern international game.

Summary

With solid expansion in the clubs and a truer reflection of the French ethnic mix at international level, France is back up and running. They are coming back from the edge of the world, and it is the world which should beware in 2023 – La France est en marche!

.jpg)

.jpg)