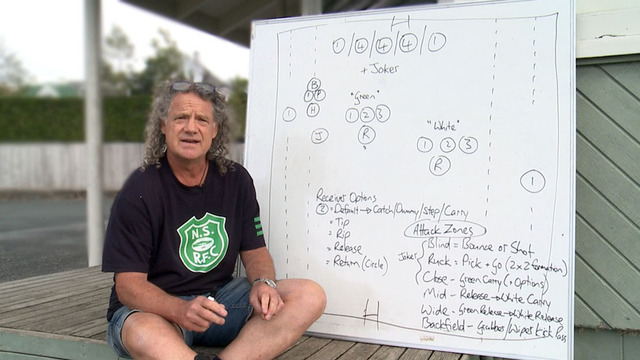

Running attacking decoy plays in theory and practice

The viability of using decoys on attacking plays has become absolutely essential at all levels of the professional game. If you cannot use decoys, or players as ‘blocks’ effectively, it is well-nigh impossible to unlock a cohesive professional defence!

Decoy runners are a non-negotiable in ‘putting the question’ to individual defenders and creating space in targeted areas of the defensive line.

Like most other things, the refereeing requirements on blocking plays tend to run in cycles. At certain times, attention will be drawn (usually by a high-profile coach) to the potential illegality of attacking players who have a real function well ahead of the ball.

A few years ago, reasonable contact on a block play was permitted. Attackers like Ma’a Nonu in New Zealand were masters at knowing just how much contact they could make with an opponent, and how much ‘necessary interference’ they could deliver, without drawing a penalty on the play.

At present referees are tending to police any kind of contact with a defender ahead of the ball more strictly, which means that decoy runners have to be very accurate with the angle and timing of their movements. They are unlikely to be able to get away with ‘chipping’ an opponent and obstructing him physically in any shape or form.

Two examples of the required accuracy on block plays occurred in the recent Rugby Championship game between South Africa and Australia in Bloemfontein. In the first example, Australia scored a very good try indeed, in the second the move was scotched quite easily.

Let’s take a look at some of the differences. In the 10th minute of the match, the Wallabies scored a try from a backs’ scrum move on the right-hand side of the field:

Australia use what is known as an “inside pass-with-block” move to open the key attacking space – in between the two South African centres, number 12 Jan Serfontein and number 13 Jesse Kriel.

The Australian #9 Will Genia runs away to the left of the scrum, dragging his opposite number Ross Cronje with him. The three attackers immediately outside him, centres Tevita Kuridrani, full-back Israel Folau and outside-half Bernard Foley all have different roles to play in order to open up the space between Serfontein and Kriel.

The crucial role of decoy is fulfilled by Kuridrani. As the most powerful and physical ball-carrier in the Wallaby back-line at 1.94m and over 100 kgs, the Springboks would have been mindful of the threat Kuridrani presented only 20 metres from the Australian goal-line.

With Cronje committed to Genia, Kuridrani is able to attract Serfontein and force him to ‘sit down’ in anticipation of making a tackle on the big Fijian:

.png)

.png)

In the first frame, the steep angle of Kuridrani’s decoy run forces Serfontein to shift inside and brace for the potential tackle, setting his feet to absorb the coming impact. Kuridrani doesn’t need to make contact with Serfontein in order to achieve his aim, the angle of his run and physical threat does it for him.

When the ball is spun behind Kuridrani to Bernard Foley – with Springbok #13 Jesse Kriel having to cover threats both inside and outside – Serfontein is left a couple of steps short in the critical gap Israel Folau is attacking from the opposite angle to Kuridrani:

.png)

The second time Australia tried a variation of the same move from a left side lineout, matters did not work out so well:

It’s basically the same idea from a lineout instead of a scrum. Here the Wallaby number 7 Michael Hooper plays the role of Will Genia, scooting off the side of a maul to engage the defenders in front of him (Cronje and Francois Louw). Australia are looking to attack the same gap as before, this time with Genia in the Foley role delivering the inside pass, and #14 Marika Koroibete playing the part of “Folau”.

The hole is defended by #6 Siya Kolisi, with #10 Elton Jantjies outside him, and it is defended with the past very firmly in mind!

.png)

.png)

Although Kuridrani is running the same decoy angle as previously, neither Kolisi nor Louw are deceived as to Australia’s real intentions. All eyes are on the play developing behind him between Genia and Koroibete, and Elton Jantjies is pointing at the zone of attack in the second frame. This was probably an example of a situation where Kuridrani did need to check Kolisi physically in order to give the play a chance of working.

Summary

Decoys or ‘block’ plays are essential in order to create gaps for the attack to exploit in the modern game.

Whether the angle of run or the potential physical threat presented by the runner is enough to ‘sell’ the decoy is enough by itself is another matter entirely. That may depend on field position and the number of repetitions – the number of times a similar play has been run before in the same game (or those preceding it).

The better the defence, the fewer the bites at the cherry.

At present it is difficult for the attack to expect a physical checking block to go unrefereed. But that may change with the next swing of law-making and interpretation.

In Rugby League for example, a decoy is allowed to make contact on the inside half of the defender’s body, but not seal him off from the play completely. For now, it remains a judgement call for the offence as to how much interference they can employ without fear of retribution from the man in charge. Research on the referee’s character and tendencies will pay dividends!

.jpg)

.jpg)