The one-two-punch: how to break down a red zone defence

In American Football, one of the besetting problems for an offensive coach is how to break down a defence in the red zone, that area in the last 20 metres of the field close to the opponent’s goal-line.

Defences often become more resistant in this zone because they no longer have to defend the depth of the field, they only have to defend its width. It is much the same in professional rugby. With such a short distance to the in-goal area, there is not much need for a backfield, so everyone can be promoted to the front line. That can make the defence very compact and hard to penetrate. If you play short, most of the time you will be running into two-man tackles.

Set-piece starters in the red zone – with the forwards still concentrated in one place, scrum or lineout – therefore represent particularly valuable scoring opportunities. The attack can count on no more than seven or eight defenders and for the most part, they know who they are and where they will be.

This is therefore, a place where you can work one play off another in rugby’s equivalent of the ‘one-two punch’ combination in Boxing. You can establish one play as a threat, then have a second play ready to run off it when the opposition adjusts.

The recent Gallagher Premiership match between Harlequins and Leicester provided a couple of very clear examples of how effective this policy can be on the attacking side of the ball.

Quins had identified an obvious mismatch in midfield in their preparation for the game. At number 12 they had selected Paul Lasike, an ex-Gridiron footballer who had been on the Chicago Bears’ playing roster as a full-back. At 6’ and 115 kilos, Lasike would have been used to ‘doing the hard yards’ and winning ferocious physical battles in short-yardage situations, both as a blocker and a runner.

On the other side of the ball, the Leicester Tigers had picked two smaller men at 10 and 12 in the shape of George Ford and Kyle Eastmond. Although both could be capable defenders, neither was more than 5’7 in height or 85 kilos in weight. If Quins could set up their plays accurately, they would have a clear advantage in size and physicality in those red zone set-pieces close to the Tigers’ goal-line.

The first opportunity for Quins to launch Lasike presented itself in the second quarter of the match, at a scrum on the left-hand side of the field:

Quins set up the move in such a way as to expose Eastmond to a one-on-one tackle on Lasike:

Half-back Danny Care runs away from the scrum on an arc in order to fix Ford (who might otherwise assist in the tackle on Lasike) and force him to stop and turn in towards the Quins number 9.

That in turn strips away the protection from Eastmond’s inside shoulder, which then becomes the target zone selected by Lasike’s run. This is especially clear on the slow-motion replay:

Eastmond makes decent contact but is simply bouldered out of the way.

Harlequins had to wait until the second half for the opportunity to work a second play from a virtually identical position inside the Tigers’ 22:

There are some important differences to note at the start. Mindful of the physical threat presented by Lasike, instead of having Eastmond defend alongside Ford the Tigers have introduced a much bigger man – number 13 Jaco Taute – alongside the England outside-half. Taute is 6’3 and 108 kilos and a much better physical match for Lasike. In other words, Leicester have reacted to what Quins achieved from this scenario in the first period.

The first half of the play looks exactly the same as the recipe for the try: Danny Care arcs off towards Ford, and Lasike runs a line crashing down on to Taute’s inside shoulder.

In reality, Quins are well-prepared to land the second blow in their one-two combination and will use Lasike as a decoy this time around. Eastmond has to defend somewhere in the line, and here he has swapped with Taute into the 13 channel, an unfamiliar position for him.

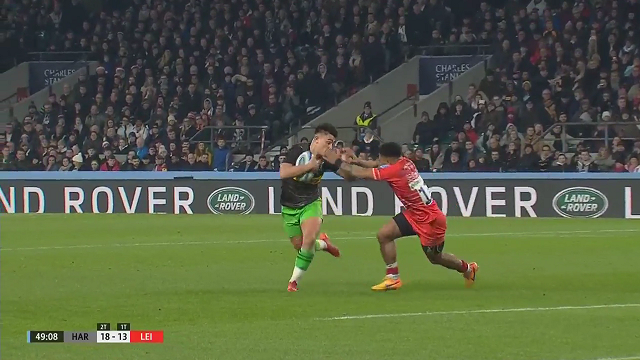

Harlequins’ response if to play the ball behind Lasike and set up another one-versus-one on Eastmond, who has swapped out into 13 channel (an unfamiliar position for him). Quins have matched him up with their running 10, Marcus Smith. Smith has quick feet and the ability to separately quickly from the defender in these situations.

At the critical moment Eastmond’s feet are too far away from Smith and he finds himself reaching for the ball-carrier with both arms. This scenario is nearly always fatal for the defender, who can be easily stabbed off with a fend:

Smith’s quickness does the rest and he scores near the posts.

The two plays taken in conjunction are a perfect illustration of the need to plan a repertoire of plays in red zone attack from set-piece, based around your strengths and how they tally with the opponent’s weaknesses. The one-two punch does not look complicated, it appears simple – but that is because all of the hard work has been done, and all of the potential issues resolved off the field, before the game!

.jpg)

.jpg)