<It is time to look in more detail at what happened when teams of the same general type played one another, or two sides of opposite approach clashed. It is safe to say that although Ian Foster might have found the semi-final between England and South Africa interesting from a tactical or coaching viewpoint, he probably found it very boring indeed as a rugby spectacle. Here’s another Fozzy soundbite from the World Cup:

“Ultimately, when it comes down to it, defences are still winning in the big games.

“Defences are standing out; the set-piece is still the be-all and end-all. When push comes to shove, they [South Africa] went to the front eight [against Tonga] and just kept going.

“That’s how they win games and allows them to dominate in areas, but ultimately, as a fan you’re seeing more kicks, one-pass carries, and that’s a problem.

“I think this is on World Rugby. This is the flow-down effect. It’s the pinnacle of the game; this is the example being set around the world and, if you want people to grow up wanting to play the game, what is it they’re seeing? Who is it they enjoy watching?”

The difference between the semi-final between England and South Africa and the quarter-final between Ireland-New Zealand was symbolic: one contained three line-breaks and one try and was decided by a questionable scrum penalty. The other featured 13 breaks, six tries and finished with one of the most momentous attacking sequences in World Cup history. As an analyst, both games are worthy of attention. But as a spectator, there is only worth the rewinding, and only one represents an attractive pathway for the future direction of Rugby.

What happened when Force met Resistance, and creative and destructive forces measured up to one another in the knockout stages? Perhaps the most intriguing encounter of all was the quarter-final between the hosts France and South Africa. The Springboks effectively lured Les Bleus into playing against type, and transforming into a possession-based team for one memorable evening in Paris. The game became a show-stopper only because France volunteered to undertake the unfamiliar role of primary creative force with ball-in-hand.

In a match of just under 35 minutes of ball-in-play time, Les Bleus had 154 carries to South Africa’s 80, built 108 rucks with over 50% LQB, and won the line-breaks by 13 to 7. The number of carries made and rucks built is very much atypical of the French modus operandi, but it made the game into a classic.

It was thus right from the very beginning:

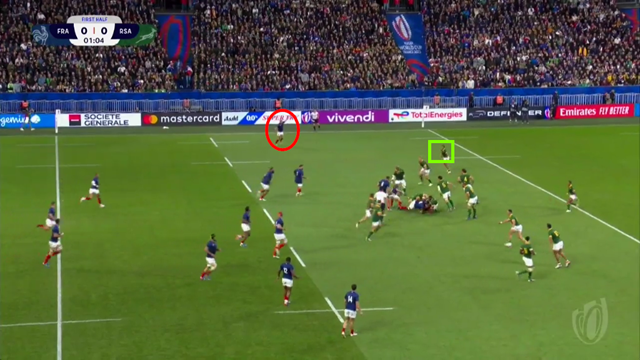

Nine times out of 10, scrum-half Antoine Dupont would cross the no man’s land between the two 40m lines with a high contestable box-kick. But it is a sign of the Tricolores’ reverse engineering for this game that he picks the high-risk chip in behind the Springbok defensive line instead. Then he doubles down with another chip into the left corner for the unmarked Louis Bielle-Biarrey [in the red hat] to chase down. Disaster for South Africa was only averted by a deliberate sweep of the ball out of play, in-goal by Kurt-Lee Arendse which went unpunished.

The first kick by Dupont was the kind of attacking chip usually reserved for strikes much further upfield. Likewise, France’s first lineout attack derived from a formation typically utilized in the red zone, inside the opposition 22:

There are two backs book-ending a nine-man lineout, with #14 Damian Penaud at the tail and #12 Jonathan Danty at the front. Danty – who is as big and as powerful as most modern hookers – provides the engine for the drive down the tramlines, while Penaud scooted between the wide and the short-side twice before setting up the try for Cyrille Baille in the right corner:

Once they were kitted out fully in their creative capes, France were not even interested in one of their attacking staples, a kick for the corner from penalty followed by a lineout drive. Dupont tapped the ball and opted for quick tempo instead:

It was a Faustian pact, and the French investment in creative attack was exchanged for some unfamiliar looseness in defence. South Africa scored their first two tries from poorly-defended high kicks, and a third from a fumble with France again trying to work their way through the 40’s with ball in hand:

Summary

The big issue emerging for World Rugby over the past two World Cups is the need to make creativity pay – both in terms of refereeing trends and the overall evolution of the game. When young coaches look for a playing model at their clubs, right now they may look no further than South Africa, or even England. That would be a calamity.

The trends established in both north and south, with Ireland winning the 2023 Six Nations and New Zealand the Rugby Championship, were ultimately not confirmed, or rewarded in the biggest showpiece event of all. While the outcome (a South African triumph) might have been right for the tournament, it was not right for the development of rugby as a whole, and that is the question that now has to be addressed.

.jpg)

.jpg)