Why have the top teams stopped kicking for goal?

The recent Gallagher Premiership final between Exeter Chiefs and Harlequins was quite possibly the best final the competition has ever seen. A see-saw, eleven try extravaganza saw Quins squeeze home by 40 points to 38, with a try in the 76th minute of the match.

The most remarkable aspect of the game was that only three points out of that total of 78 came from a penalty goal attempt – in the 66th minute, from directly in front of the posts. The other 75 points all derived from tries and conversions.

That tells you a great deal about the future direction of the game. The relevant stats are quite startling:

• Out of a total ball-in-play time of 36 minutes and 10 seconds, 22 minutes was derived from penalty goals kicked into touch within the opposition 22m zone.

• Out of 10 kickable penalties within the opposition 40m area, there was only one kick for goal. The remainder were set as lineouts (after another kick for touch), scrums or taken as tapped penalties.

• Harlequins opted for position off kickable penalties on six occasions. They lost two lineouts, but the other four sequences generated three tries, two conversions and two yellow cards issued to the opposition for offences close to their own goal-line.

• Exeter opted for position on three occasions, and kicked a goal on the fourth. They maxed out, with seven pointers out of three attempts close to the Quins goal-line, and one yellow card issued to the opponent for repeated offences.

The two sides generated 40 points scored, and 30 power-play minutes in which the opponent had to play short-handed – by directing their penalties to touch, rather than attempting kicks at goal. Even if they had converted all of those kickable attempts, the maximum return they could have made would have been 24 points.

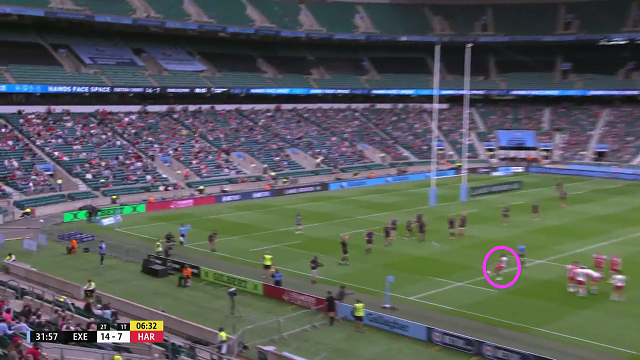

The old rule of thumb used to be that you kicked for goal if the position was in the box formed by the two 15 metre lines and 40 metre line; and kicked for touch if you were outside it. In the Premiership final, the envelope was pushed even further, with both sides refusing kicks in midfield at point black range:

The game was probably won and lost in two long sequences towards the end of the first period. When Harlequins were awarded a penalty in the screenshot at 31:55, they already were down to 14 men, with a player off the field on a yellow card.

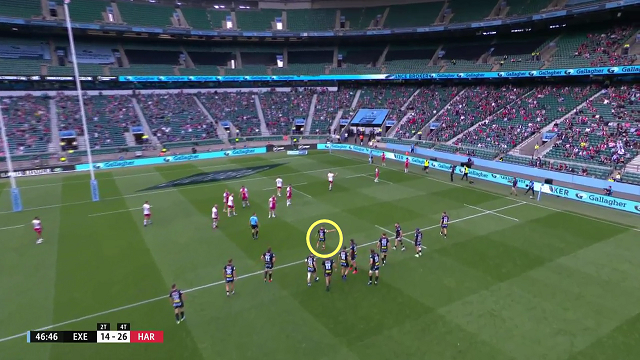

But they held on to that position for long enough (seven minutes and five seconds) both to score a try short-handed, and to run down the clock on the card to zero.With the clock moving into the red in the dying embers of the first half, they then kept the ball for another five and a half minutes in the Exeter red zone, before scoring a try in the 47th minute.

The structure of the tries had much in common. They both started with open-side pick-ups from scrums and then returned to the site of the set-piece after first phase, with the risk factor minimized.

In the first instance, there is a simple switchback to the short-side after a pick-up by the number 9 on first phase. The defending forwards are still in recovery mode after pouring themselves into the defence of a five-metre scrum:

By the time the conversion had been taken, the yellow card had wound down to zero.

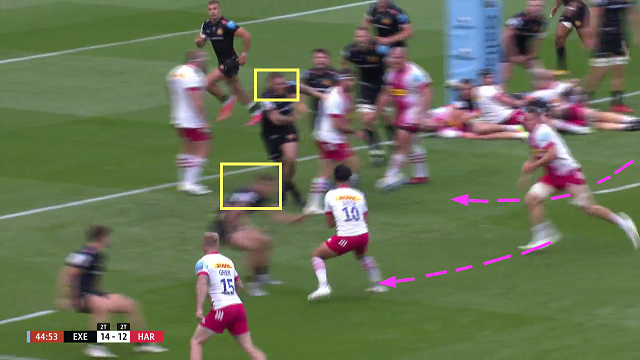

The same principle was at the heart of the second try. After a pick-up at the base by the scrum-half, play shifted back towards the Exeter tight forwards via late movement across the back of the ruck by the Harlequins’ number 10 Marcus Smith and the number 8 tracking inside him, Alex Dombrandt:

The Exeter forwards are too spent from their efforts at the set-piece to cover the space out to the first defensive back, allowing Dombrandt to canter through the gap untouched. That was the go-ahead score for the Quins.

It may just be the end of an era. The days of the penalty goal as the primary means of scoring in Rugby may be coming to end – at least if the English Premiership final is a true measure of judgement.

Establishing, and maintaining position in the opponent’s red zone is far more important than a meagre three points on the scoreboard. Not only is there is a probability of seven points rather than three, but there is the added bonus of looking forward to playing the following 10 minutes against 14 men, with repeated offences in the red zone more likely to be punished by a yellow card. Possession may, after all, be nine-tenths of the rugby law.

.jpg)

.jpg)