Why the cross-kick is a quick fix for attacking width

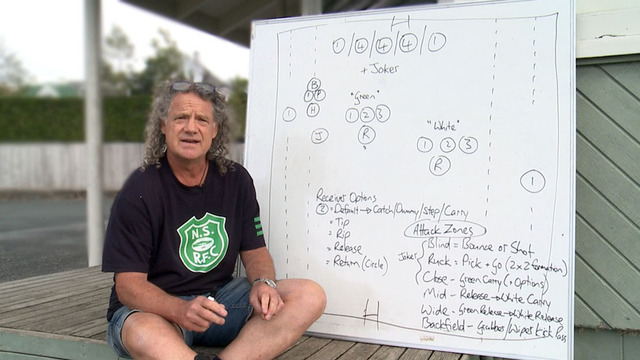

In rugby at all levels, it is axiomatic that it coaching effective defence and forward play is much easier than building a productive attack. The more ambitious your attacking plans, and the more width you want to create, the more time and patience it takes to allow the pieces to fall into place.

Back in the early 2000’s, the England national team were facing the same dilemma. Like most England teams, it enjoyed a strong forward platform at the set-pieces, and under the coaching of Phil Larder it had probably the best defence in the world.

But head coach Clive Woodward wanted more. He wanted a side which could get the ball wide, and play 15-man rugby when the occasion demanded. He wanted more than the traditional English formula, which had historically never been enough to win a World Cup.

The England coaches knew that their players would probably never be able to match the skill-sets of their counterparts in New Zealand and Australia, so they turned to a new weapon in order to achieve width. With the help of an outstanding kicking coach in the shape of Dave Alred, they developed the attacking cross-kick.

The cross-kick (or kick-pass) is a low-risk way of moving the ball from one side of the field to the other in one movement, without the need for top-drawer handling and passing skills.

It can be used in all parts of the pitch, and is especially effective when the defence is either playing ‘off’, or struggling to maintain width on the far side of the field.

The cross-kick can be broken down into two parts: (1) how to maximise the chances of a successful kick and catch, and (2) how to load the dice in your favour after the receipt is made.

Two recent examples occurred during the premier provincial competitions in either hemisphere – the Heineken Champions Cup in the north and Super Rugby in the south.

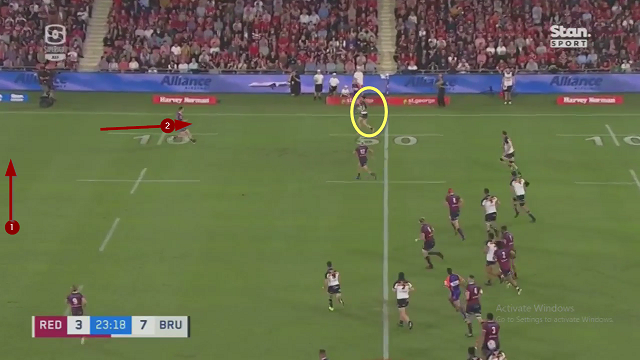

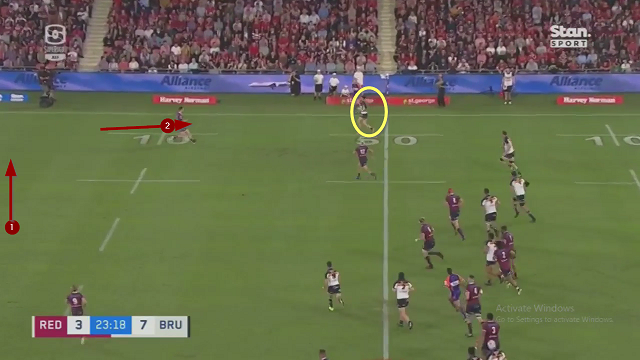

During the recent Super Rugby AU final between the Brumbies and the Reds, the men from Canberra saw an opportunity to cross-kick at midfield:

The first point to notice is that the cross-kick does not cover the full width of the field – far from it. It takes two passes to reach the kicker (Noah Lolesio) from the ruck, and he addresses the ball from a position about 10 metres inside the 15-metre line, and roughly level with the near post. The ball will cover a maximum of 40 metres (less than 60% of the full width of the field) before it reaches its target – Brumbies wing Andy Muirhead out on the right.

What makes the kick attractive? The last defender is playing well off the line in the backfield, and he has to run all the way from his own 22 to make up ground and close on Muirhead:

When the Brumbies winger makes the receipt uncontested, he has a positive choice to make – he can either keep the ball and try to beat his opposite number one-on-one, or he can kick through in behind him and establish a pressure position deep in the opposition 22. With the second Reds’ backfield defender having to run from a position on the ‘wrong’ side in cover, he chooses the second option.

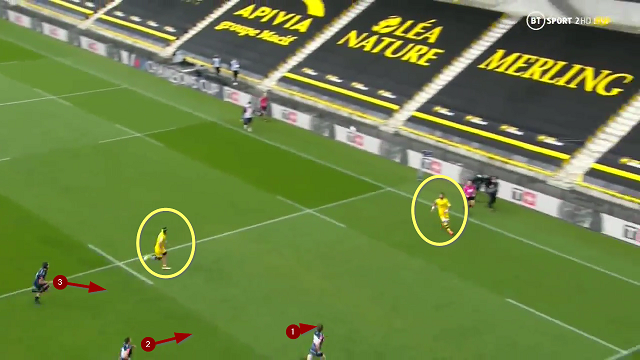

The second example comes from the European Champions Cup quarter-final between La Rochelle and Sale:

As the camera shot opens up at 28:43 on the clock, it becomes obvious that Sale (in the blue jerseys) are struggling to regain width on the right side of their defence, so the La Rochelle number 10 (Ihaia West) picks the quickest way of getting the ball to the two unmarked attackers on the left side-line: the kick-pass.

Once again, the kick is made from a position level with the near post, so the ball will travel no more than 35 metres in the air. The other bonus for the attack is that they do not need a back ready to catch the ball – the two players out on the La Rochelle left are both forwards (back-rowers Victor Vito and Greg Alldritt).

All the attacking team is trying to achieve is a situation with the first support player at least level with the first cover defender:

The cards tip out in their favour: Vito is able to step inside the first defender (who is running hard for the corner) before offloading to Alldritt for the score. Here is the sequence from the overhead angle:

For teams who like to prioritize forward play and defence, or simply don’t have the time or skill-sets needed to build a sophisticated attack, the cross-kick makes a lot of sense. You can achieve width quickly with a low risk factor; from upfield positions, you still have the option of kick or run after a successful catch. Closer to the red zone, you don’t even need a back on the end of the kick in order to make significant inroads. What more could you want?

.jpg)

.jpg)