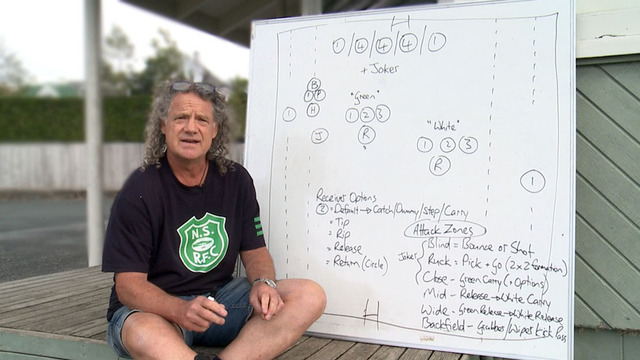

There is still a place for the small man in what is fast becoming a very big man’s game. The emphasis on physical size and power and the winning of collisions seems all-consuming, but in fact it leaves space for the small, quick player to thrive in the seams between behemoths.

Four years ago I wrote an article inspired by Shane Williams’ Rugby Site session on the sidestep. You can still find a neat precis of the original piece here.

One of the conclusions from the article was that, in order to overcome the deficit in size and power, the small attacker had to be able to brake in one step, and change direction in the second. Lateral movement had to translated into forward momentum immediately. This is the kind of manoeuvre which is typically beyond the scope of a much bigger man.

Since the retirement of Shane Williams, the two best small men in the modern game have probably been New Zealand’s Damian McKenzie, and South African Cheslin Kolbe, who plays his club rugby in the South-West of France, for Stade Toulousain.

Kolbe has had the opportunity to showcase his skills in the delayed knockout rounds of the European Champions Cup over the past two weeks.

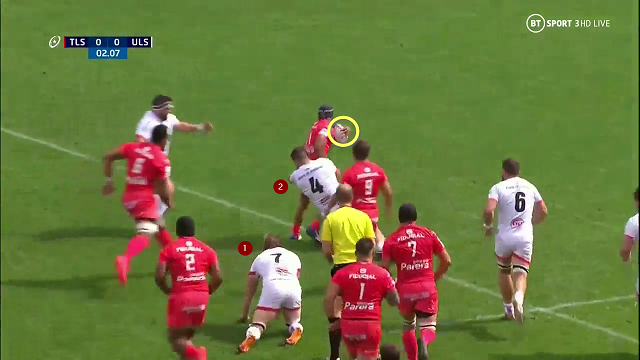

Toulouse’s first try in their quarter-final against Ulster was classic Cheslin Kolbe, and it satisfied all of the theoretical requirements:

When the ball is spun out to the right, Kolbe is faced by a much bigger man on defence in Ulster’s number 11 Jacob Stockdale. Stockdale is over 6’3 and 100 kilos, Kolbe is 5’7 and 75 kilos, so the diminutive Springbok wing is not running over the top of his opponent.

The key from our viewpoint is how quickly Kolbe straightens after stepping off his right foot to beat Stockdale – the first stride takes him inside the Ulster wing, the second straightens his line instantly and takes him away from the cover defender. There is no time for the defence to recover once the mini-break has been made.

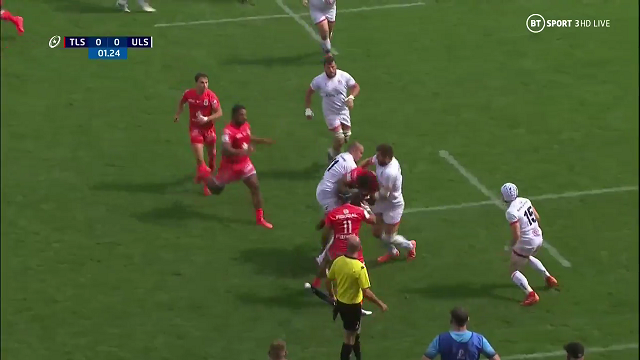

A second example from the build-up to that try is more complex, and illustrates some of the other important themes discussed by Shane Williams in the short video:

After beating both Stockdale and Ulster’s other ‘big back’, number 12 Stuart McCloskey (6’4 and 111 kilos) near the right side-line, Kolbe is faced by two forwards, numbers 7 Jordi Murphy and 4 Alan O’Connor on the inside.

In his video presentation, Shane Williams observes that the sidestep is not just for the purposes of beating a defender. Even if the tackle is made, it is likely to be completed with the defender reaching for the attacker with a low arm tackle. This means that the attacker will be able to keep his own arms free to offload to supporting players.

Kolbe first steps Murphy off his left foot, then straightens within one stride and forces the low tackle from O’Connor. At the key moment the ball is available for the offload; the worst outcome is that Kolbe will be able to fall forward and create a very positive ruck for the next phase:

The proviso to these benefits of the small attacker is that his/her contact skills on attack must be accurate enough to offset any disadvantages in sheer size. Kolbe had satisfied any doubts on that score within the first 10 minutes of the match:

The Toulouse centre Sofiane Guitoune is momentarily isolated, and in real danger of being help up by Ulster’s two big backs, Stockdale and McCloskey:

Kolbe is the only support in attendance, but he is able to rip the ball out, regather and set a very small target for the regrouping Stockdale and McCloskey on presentation.

Kolbe had to deal with McCloskey again a few minutes later, this time on the cleanout:

Once again, the Toulouse ball-carrier is temporarily exposed and Kolbe is faced by a one-on-one cleanout against the big Ulsterman. He has the technique to get low enough – lower than his opponent – to rip one of McCloskey’s arms off the ball. That is all he has to do. When the centre goes back in on the ball for a second dig, it is already illegal movement:

.jpg)

.jpg)