Wind the clock back to the middle of March, and you will find an interesting discussion on Sky Sport’s The Breakdown show promoted by ex-All Blacks wing and full-back Jeff Wilson. It revolved around the attitude of support players on attack at cleanout time. ‘Goldie’ compared the attitudes in New Zealand Super Rugby unfavourably to those in the Northern Hemisphere, and especially in Ireland:

“Watch where they clean, and how they clean through. They don’t look at the tackler, they are looking at the space beyond the ball, with heads up – being dominant and creating opportunities. It creates quick ball and depth to the breakdown, and all of a sudden you have a hole and space to attack through…

That first support player is always looking to stay on their feet, drive them [the defender] backwards and create quick ball – not going to ground.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G5DB0nTJx-w [from the 18th minute of the show onwards]

Jeff’s Wilson main example came from the second try in Ireland’s end of year game against the All Blacks:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-eJP5EmRZcs [at 6:20 on the highlight reel]

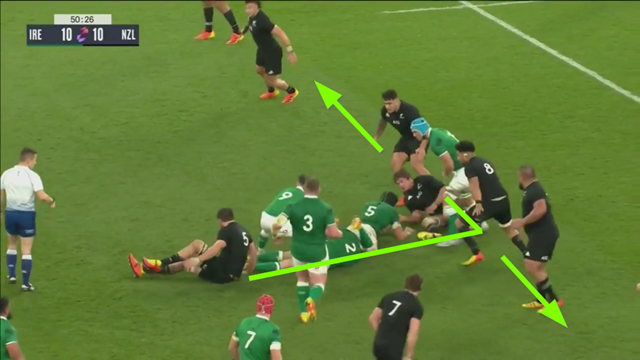

The key moment isolated by Wilson can be found in this screenshot:

The ruck is at least two metres deep, with a pair of Ireland forwards (Tadhg Beirne and James Ryan) well ahead of the ball and creating an offside line for the New Zealand defenders far removed from the halfback Jamison Gibson-Park, who can set up the next play in his own time and space.

In fact, the situation is far more nuanced than Jeff Wilson was able to suggest in the time allowed. There are definite dangers associated with the first cleanout player operating as a maverick, taking out defenders well ahead of the ball and becoming disconnected from the second man:

In this instance, the Highlanders’ Josh Dickson launches well across the tackle, and goes off his feet to take out his opponent, Lukhan Salakaia-Loto. It is the kind of scenario which could easily have attracted a penalty against the attack in the Northern Hemisphere, and one which has no obvious upside for the offence.

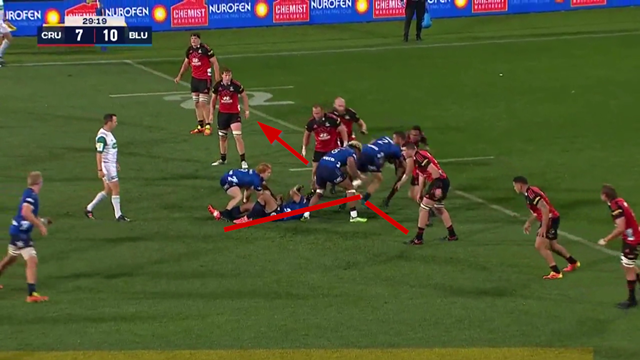

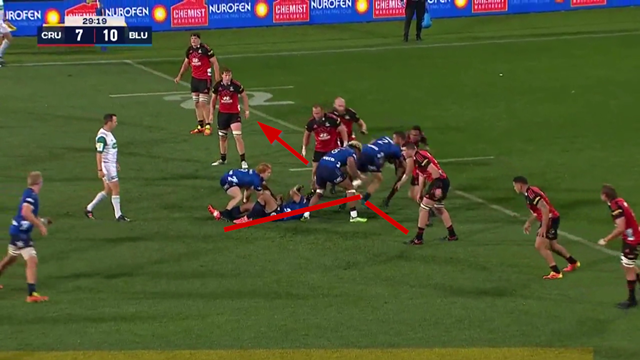

Any degree of separation between the first two cleanout players can create problems:

The Blues’ Tom Robinson launches off feet to take out Rebel back-rower Rob Leota ahead of the tackle, and that exposes the ball to a steal by the first arriving player, Rebels’ number 7 Richard Hardwick. There is too much space, and an evident disconnect of purpose between the first two cleanout players.

Northern Hemisphere referees tend to be more mindful of this disconnect, and more willing to penalize it when it happens:

This instance comes from the end of year tour match between Scotland and Australia. The Wallabies work a nice move around the tail of the lineout to fire Leota straight at Scotland number 10 Finn Russell, and on this occasion the second support player (Jordie Petaia) does his job on the poacher. The problem is that the first Wallaby cleaner (Hunter Paisami) runs Russell out of the play fully six metres behind the site of the tackle, and that attracts a penalty from French referee Romain Poite, while denying the try Australia scored on the following phase.

The first cleanout player has to control his distance ahead of the tackle, like Liam Coltman in this example:

Unlike Paisami, Coltman stops short of running Reds’ full-back Jock Campbell completely out of the play. He has already established the favourable ruck perimeter needed to launch centre Fetuli Paea on the following phase.

What do we mean by ‘favourable ruck perimeter’, when the first two cleanout players keep their sense of connection? Let’s take a look at two short-side attacks by the Blues in their Super Rugby Pacific game against the Crusaders:

Here is the situation Jeff Wilson observed in the Ireland-New Zealand match. Both cleaners (Kurt Eklund and Hoskins Sotutu) are well ahead of the tackle, they are connected and they are still on their feet. The breakdown has the requisite depth to implement an attack on the short-side on the phase following.

The Blues botched the opportunity on this occasion, but they put the wrongs right only a minute later:

Both Sotutu and second row Josh Goodhue have advanced ahead of the ball and they have created a comfortable pocket of protection for their scrum-half Finlay Christie. The advanced ruck perimeter, with Goodhue ‘on point’ effectively splits the Crusaders in half, making it far more difficult for the two defenders who could have made a difference in cover defence (halfback Bryn Hall and number 8 Cullen Grace) to get across to the try-scorer, Blues number 7 Dalton Papali’i:

Both Grace and Hall are a step or two short in the scramble, and the Blues’ captain has the room he needs to touch down.

Jeff Wilson’s short presentation on The Breakdown raised some interesting questions around attitudes at the cleanout. Although the aggression to attack the space beyond the tackle has always been present in New Zealand rugby, it also involves some risk, and it is easy to get the balance wrong.

Summary

The first two cleanout players have to remain connected, and the first support has to be careful not to run his man too far out of the play, or launch off his feet beyond the ruck perimeter. If both players can advance beyond the tackle in unison, chances are they will create that protective pocket their half-back needs, and open up some attacking opportunities with the defence split into two units

.jpg)

.jpg)

_no_button.jpg)