In the NFL, three are many different techniques an offensive lineman can use in order to spring the running back behind him into an inviting hole. Sometimes it is all about straight-ahead size and power – so-called ‘smash-mouth football’ – but on rather more occasions, it is not.

The very best offensive linemen know how to drive-block (straight ahead), but they are also able to ‘trap’ defensive players on the interior of the line, and have the mobility to ‘pull’ to the outside and lead sweep plays to the outside of the field.

One of techniques which has been most easily transferable to rugby is the ‘wall’ or ‘down’ block. In the wall block, instead of driving off the defender with power, the offensive player looks to position himself in between the defender and intended path of the next ball carry and wall him off from the play.

The following video explains the philosophy and practice behind wall or down blocking https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KOK8VWr-bgM . The blocker starts at a 45-degree angle and keeps moving the defender in the same direction, away from the path of the next carry.

So how does this skill transfer to rugby? The breakdown cleanout is blocking by another name. The cleanout ‘blockers’ are ahead of the ball and looking for ways to gain advantage over the defenders in the same area.

By angling the cleanout at 45 degrees, they can increase the space between the ruck and the first defender next to it. This can immediately benefit the attacking scrum-half by creating a wider channel for him to exploit. The following example comes from the recent European Champions Cup game between Montpellier and English Premiership champions Harlequins:

There is still a Montpellier defender on his feet contesting the tackle ball when the second man, Quins number 5 Hugh Tizard, sees the opportunity to use an angled cleanout to narrow the width of the ruck and develop space for scrum-half Danny Care to attack:

The replay from behind the ruck illustrates how Tizard’s block removes the offending Montpellier backside, and allows Care to use a step off his right foot to split the two Guards on either side of the breakdown.

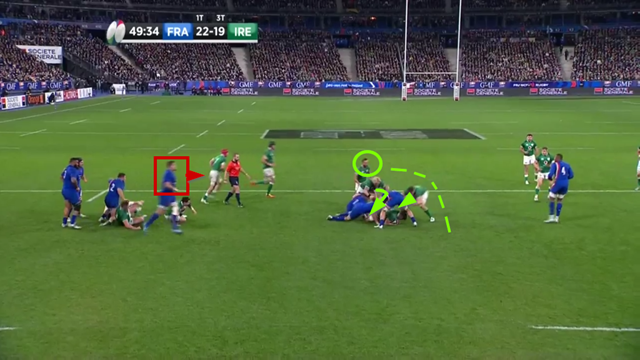

The scrum-half is usually the beneficiary of angled cleanout blocking. This example comes from championship decider between France and Ireland in the Six Nations:

The two main Ireland cleanout players (number 8 Jack Conan and loose-head prop Andrew Porter) are not trying to drive the defender (France number 8 Greg Alldritt in the hat) straight backwards. They are looking to wall him off to the Frenchman’s left at a 45-degree angle.

After that objective has been achieved, it becomes a race to the hole created, with Irish scrum-half Jamison Gibson-Park (in the green circle) the clear favourite ahead of the French second row Paul Willemse (in the red square). There is only one winner of that contest once the space has been levered open on the opposite side of the ruck to Willemse, and Gibson-Park’s inside step does the needful.

Angled cleanouts can be of particular value near the opposition goal-line:

https://gfycat.com/scratchyshorttermdragon

This instance comes from the last stages of the Super Rugby Pacific match between the Queensland Reds and he Fijian Drua. After Queensland number 7 Fraser McReight hits the ground one metre short of the goal-line, Reds second row Ryan Smith has to block ‘down’ on the Drua number 11 in order to remove the threat, take the defender to the opposite side of the ruck, and create just enough of a hole for flanker Seru Uru to jump forward and score.

Angled cleanouts can benefit any attacking player who occupies the acting half-back role, not just the scrum-half:

In this example from the game between Queensland and the Brumbies, Reds number 14 Jock Campbell does not want to drive Brumbies number 12 Irae Simone straight back, he wants to shift him from left to right to lever open another hole for the acting half-back (Uru again) on the pick & go.

That enables the big Queensland back-rower to split the seam between the two Guards on the opposite side of the ruck (Nic White and Darcy Swain) and make a long break downfield.

Summary

The cleanout is not just about power and ‘smash-mouth’ collisions. Increasingly, cleanouts that depend on pure power run the risk of head-high contact performed at high velocity. More finesse is needed, and angled cleanouts – ‘wall’ or ‘down’ blocking in American Football parlance – can create space around the sides of the ruck without running the same risk of dangerous contact to the head or neck. It is an option well worth considering for any modern phase offence.

.jpg)

.jpg)

_no_button.jpg)